It must have been 20 or more years ago when I first met Jason Fritts. I don’t know the year, exactly, but I recall the cirumstance. I was on my annual weeklong camping trip to Winfield, Kansas, attending the Walnut Valley Festival, a popular acoustic music event held less than an hour away from Wichita. On this particular occasion I was roughing it in a tent in a little campsite shared with several other friends. We were set up on a treeless mound, one of the higher spots in the Pecan Grove — not a bad place to be in the inevitable rains of September, despite the complete lack of shade on sunnier days.

Directly adjacent to our campsite to the west was a wide, shallow, grassy gully. It was like a gentle wrinkle in the earth, several feet deep where it touched the dirt road to the north, but level with the lower road to the south. Any time there was a half-inch of rain, this area became a temporary river as water from across the grounds drained through and dumped into the Walnut River, only a few paces to the south. It seemed an ill-advised place to set up camp. And yet there were a couple tents down there, straddled by a banner announcing the campsite’s name — WE’RE IN A TIGHT SPOT — stretched high above the ditch on two tall posts planted in the earth.

“Jeez, that is a tight spot,” I chuckled to myself, looking down the slope toward the tents below. “I guess as long as the weather holds out, they’ll be OK.”

Some time that week I was over at another campsite down the road a ways, having laughs with some old friends, when a friendly teddy bear of a man sauntered up to me and introduced himself as Jason. I recognized his face from bars and music venues around town, and he told me he had seen me performing in one or another of my bands. We started chatting and it quickly became clear that we had a lot of friends in common. He told me he was camped at Tight Spot.

“No way!” I replied. “We’re neighbors!”

“I know!” he laughed. “Hey, what are you doing right now? How about we stop by there and stock up on some of these stouts I brought and go on a walkabout?”

It sounded positively agreeable to me, so we did just that. Back at his camp he led me to a little shrine set up next to a tree; the central figure was a plaster statue of a kneeling woman with one arm reaching up to her left, sitting on top of a decorative plaster Ionic column, swathed lavishly in Mardi Gras beads and festooned with small charms. “This is the Goddess of the Grove,” Jason explained, pulling a couple stout craft beers out of a large cooler and putting each of them into a koozie. “We have to pay tribute.” He cracked open both cans, handed one to me and held his aloft in a toast to the Goddess. I followed suit, then we both took big drinks in unison.

And with that, we set off on a long, langorous stroll around the whole of the Pecan Grove, stopping frequently to talk with various people we knew, and more than a few we didn’t. Jason was so laid-back and easygoing, I don’t think there was more than five minutes that day when he wasn’t actively smiling — and his effortless geniality was contagious. I laughed a lot on that walkabout and was really happy that he had invited me along.

This was typical of my earliest interactions with Jason, and the generally warm and fuzzy tenor of the times we spent together over the years thereafter never faded. And I certainly wasn’t the only one; most everyone I know seemed to know and love the guy. Wherever he popped up he was sure to be spreading the most earnestly sincere good vibes. People would called out, “Frittsy!” and hug him, take selfies with him — and in every picture you see, he and everyone else are wearing their biggest, most genuine smiles.

Over time, Jason and I became better friends, but any time I was curious about his past — where he had come from, his family, school days — he had a way of deflecting my questions as though none of that was important. It was clear he was crazy about soccer, his chief passion; I learned that in his earlier, more athletic days, he had been a keen league player. I already knew he was a great fan of live music, and we had many discussions on a wide variety of musical topics. He also knew a lot about kinesiology and related areas of medical study, having worked in that field; when I told him about my congenital foot deformation, he surprised me with his detailed knowledge of my condition and possible courses of remedial action I might consider seeking out. In fact, he once even brought me some really helpful shoe inserts. But any time I asked deeper questions, he tended to wave them away. Sometimes his ever-present smile would dissolve into a momentary trace of a wince when asked about something he would rather not discuss. I knew better than to press.

Our friendship finally bloomed into full flower at the time Jason became a surprise middle-aged dad. The same thing had happened to me just a few years before, and he had watched me overcome an initially rocky custody situation and grow into a parent he considered worthy of consulting for advice. I was honored and flattered, of course, but also a bit bewildered at Jason’s lack of self-confidence in his own fathering. This deeply empathetic, patient, kind sweetheart of a man worried endlessly that he wasn’t going to be “enough” for his boy.

I don’t know how many times we would be talking about something my boys were into — goofing around with musical instruments, using a telescope, flying model rockets — and Jason would say, “See, I want to do cool stuff like this for my son.” Though it was obvious to anyone with eyes that Jason adored Joey and always did his best for him, the poor guy was perpetually plagued with a nagging feeling of inadequacy. It really made me sad to see it.

“Jason,” I told him countless times, “you don’t have to spend a bunch of money or jump through hoops to be a good dad. You have everything you need inside you already, and you are already doing it.”

I wish I could believe that he took that to heart, but I don’t know that he ever entirely did. He seemed to always second-guess himself.

As Joey got older, Jason and I more frequently got our boys together for playdates. My younger boy is just about the same age and all three of them play well together. The summer before last, 2019, we all went to the Bartlett Arboretum in nearby Belle Plaine on Father’s Day to see legendary fiddler Byron Berline play. After the show we walked the breathtakingly lovely grounds and Jason pushed Joey in the swing near the pond. It was an idyllic afternoon, well shared.

Once in a while he would bring Joey by our house and all three boys would go over into our neighbor Caroline’s vast, park-like back yard and climb trees and run around like monkeys. And while the boys played, Jason and I would talk. By this time I had lost my business and declared bankruptcy and was struggling both financially and mentally/spiritually. Jason always had something positive to say, even though he was facing his own ongoing tribulations. His work life, comprised at the time mostly of a few bartending shifts each week, was becoming less steady by the minute. On one occasion he asked me what I did for health insurance and I told him I didn’t have any. At the time I was a member of Atlas MD, a local concierge clinic that charges a monthly membership with no cost for office visits, plus cheap prescriptions, etc., and I suggested he consider joining himself.

“But that doesn’t count as insurance for Obamacare purposes, does it?” he asked. “Don’t you have to pay a penalty when you file your taxes?”

“Ostensibly,” I said, “but the penalty is a lot cheaper than the insurance, not to mention I don’t have to pay out of pocket for co-pays any time I go in to see a doctor.”

He said he’d look into it, but I don’t know what decision he came to, if any.

In 2020, when COVID19 first became a public health threat, Jason was one of the few people outside my own household who was allowed in our “bubble.” I barely left the house, my kids were out of school and their mom was working from home, so we were pretty well isolated. At the time Jason was similarly cordoned-off, too, and he was good with virus protocol overall — a by-product of his clinical experience, not to mention just his being a considerate human being. While our city council members and our state’s sensible governor were being lambasted by right-wingers for enacting stay-at-home and mandatory mask orders, Jason and I strategized ways to keep up our occasional playdates with minimal chance of cross-contamination.

For Father’s Day that year, we met at Botanica, which was, to our delight, almost entirely abandoned, and enjoyed some socially-distanced nature time. It had been several months since I had been in any public place other than the grocery store, and walking around the empty, ornate, well-kept gardens in complete silence was supremely odd, almost a little unsettling.

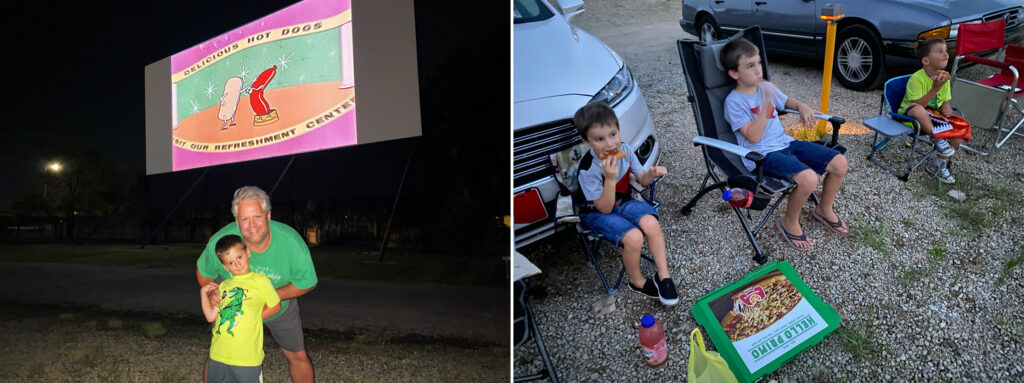

In July we met at the drive-in movie theater to see a double feature of Jurassic Park and E.T., all of us seated in the open air in lawn chairs in front of our adjacent parked cars. A week after that Jason once again proved himself a true friend when he accompanied me in a U-Haul van down to my old hometown to help me finish loading up the last of the furniture and things from my grandmother’s house and move them back to my place in Wichita.

It was that day I saw his poor Pontiac for the last time, parked in the lot at his apartment building with the entire front end smashed in. He had been driving the dilapidated hulk for more than a decade, and before that had owned a similarly decrepit one much like it. I wasn’t alone in my astonishment that it was still running in 2020, but I do have to admit I felt terrible for Jason when it came to such a sudden and unexpected end — a simple no-injury rear-end impact. A line of fast-moving cars had come to a quick stop in front of him where there was no shoulder, so he hit the car in front of him square on. He spent the rest of the summer and fall looking for another car he could afford. He sent me links to a couple online classifieds to ask my opinion of them, and I sent him a few too, but I don’t think he ever found anything, though he did manage to borrow a car (another old Pontiac!) from his sister for a while.

After that day I think I only saw Jason in person one more time, in August. I remember it well, as he called up and asked if I wanted to bring the boys to meet him and Joey for an impromptu nature walk at Pawnee Prairie Park, a place neither my sons nor I had ever been. To be honest I was really struggling with depression that day, and I didn’t want to go at first. But the weather was nice — remarkably temperate for August in Kansas — and I figured my two boys would enjoy it, so I agreed.

I was so glad I did. Along the considerable length of nature trail in the park, we saw so many beautiful flowers and plants — Monarch butterflies mating in the trees, wild bunnies and other critters skittering in the brush. I thanked Jason for having invited us, and I meant it. All these years later he was still taking me on walkabouts, and they were still worth it every time.

Jason had by this time developed the habit of calling me regularly on the phone — always out of the blue — to shoot the shit. I finally had to ask him to start texting me before calling. I of course truly enjoyed our long, generally laugh-filled, often meaningful conversations — but Jason was an old-fashioned phone talker who could easily keep up and even surpass me in the rambling-on department, and every time I saw his name on the caller ID, I knew if I answered the phone it meant I would be on the call for 45 minutes. My mental health has been challenging in recent years, and I am not always up for a long bull session — but I didn’t want to hurt his feelings, either, so sometimes it was too hard for me to just tell him so. I don’t know why I was so afraid to say anything, because when I finally did, of course Jason understood.

Fall rolled around and my kids’ school, to my great disdain, opted for in-class teaching, so the boys started going to school every day, exposing themselves to hundreds of other kids. Before long my oldest was sent home to do “remote learning” for two weeks due to a COVID infection in his class. A month or so later he got sent home for another two weeks when one of his teachers tested positive. Jason invited us out a couple times during these periods, but we had to beg off. The last conversation of any length he and I had was in late October, when he offered me a roll of chicken wire he thought I might want for my backyard coop. That was during my son’s second remote-learning spell, so I told Jason I would have to come fetch it later, if he didn’t mind hanging on to it for a while.

And then, a few weeks later, on November 29, Jason made a pair of Facebook posts. The first, accompanied by a cute GIF with the legend, “I love you (even when we are six feet apart),” read:

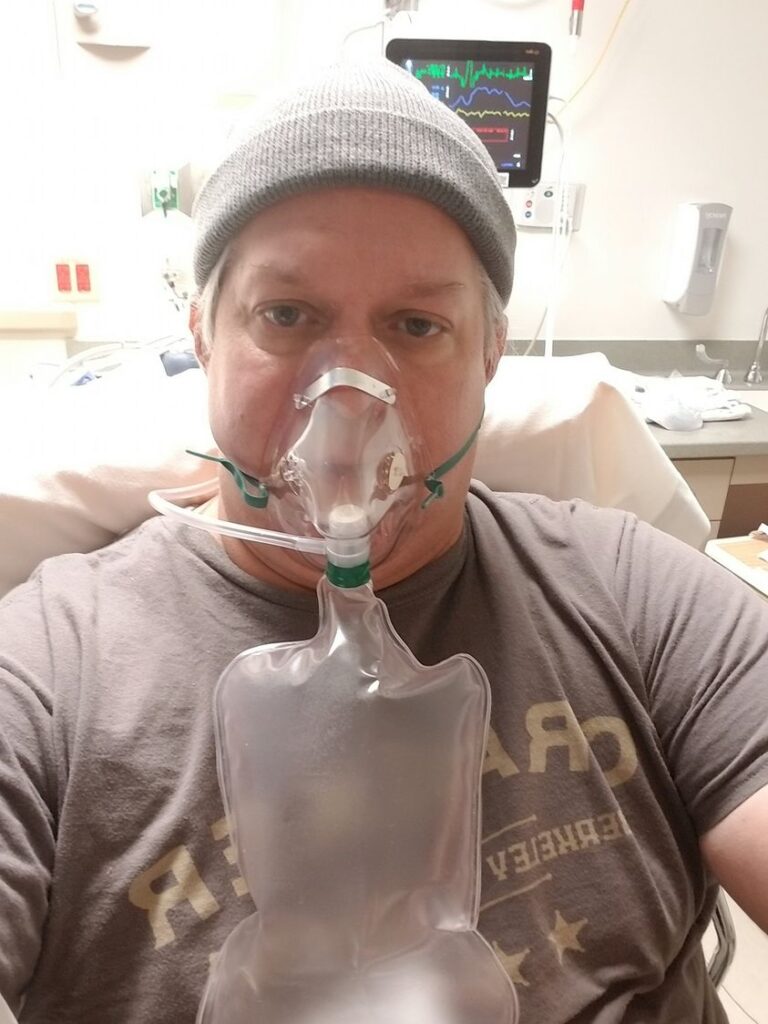

Well, i guess its time to come clean. Its not that i was trying to keep it hidden, i just didnt have the energy to focus. I have Covid-19, and its been really bad for me. I cant sleep, my lungs are weak bc i cant take deep breaths. Fever is everyday. This is day 10. I cant eat things unless they are sweet, everything is like eating those joke jelly beans or something. Trying to find some witty humorous quips to make this interesting to read. I need a primary care doctor if you have any recommendations. Please wear your mask.

The second post consisted only of this image:

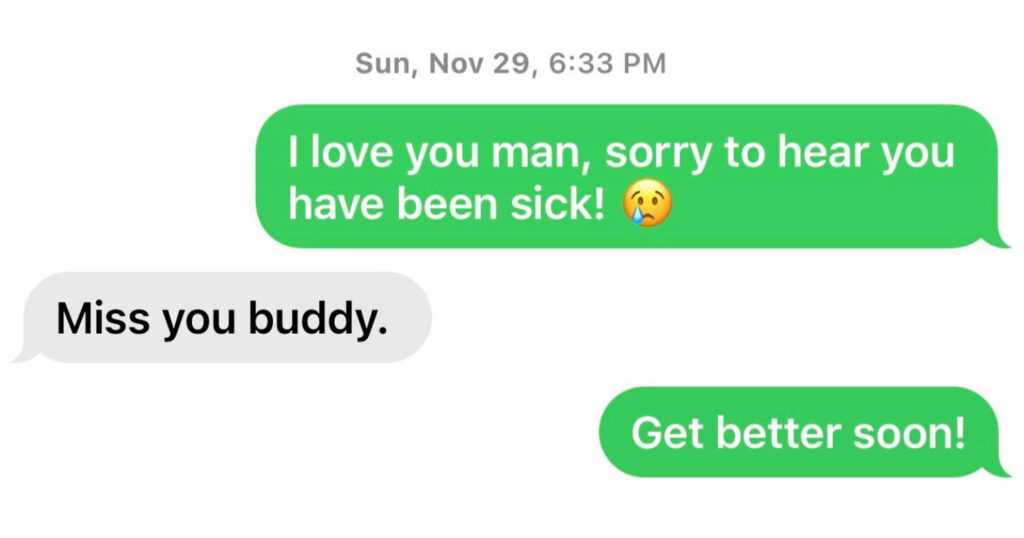

I was horrified. I immediately pulled out my phone and sent a text, and he answered right back.

When I texted him again a few days later to check on him, he did not respond.

As it turned out, by the time he was admitted on Nov. 29, Jason was already in dire need of treatment. He had actually been sick for almost two weeks but didn’t seek medical care until he was gravely ill, as he either didn’t have insurance or couldn’t afford the co-pays for whatever insurance he did have. He hoped he would be one of the lucky ones who got a little sick, then got better and went about their business as though they had contracted nothing worse than a mild flu.

But after three days in the hospital struggling to breathe, he was placed on a BiPAP machine in hopes of getting his blood oxygen levels up. When this failed, Jason was put under sedation; a plastic mask was placed around his mouth and nose and a large plastic tube inserted down his throat so that a ventilator could start supplying oxygen directly into his lungs full-time.

Joey’s mom, Christa, with whom I had only really just become acquainted, was kind enough to keep me in the loop with updates on his progress. On Dec. 10, there was cautious optimism. But then by Dec. 14 (coincidentally, my birthday) Jason’s kidneys started failing, and he was put on dialysis. On the 18th the doctors were starting to have concern over the effects of long-term intubation.

On December 20, just before Christmas, Christa dropped Joey by our house and I took him and my boys to Riverside Park to play. I made them keep their masks on and told them to keep a good distance from the other kids, and they all really did a great job — but it was a lovely warm day out and there were at least a couple dozen other kids there crawling all over the playground equipment, with not a single mask among them. I let the boys run around for maybe 30 minutes but all I could see was a giant Petri dish and it skeeved me out. I corralled the boys back into the car and took them through the Braum’s drive-thru for ice cream.

The 23rd brought the sobering news that Jason had “coded” and that it had taken something like ten minutes to bring him back and stabilize him. The next few days the updates balanced good news and bad news, up and down. Every time I dared think maybe he was going to pull out of it, some other indicator of his health would take a nosedive.

On Sunday, the 27th of December, I made a Facebook post noting that it had been four weeks since my last communication with our good friend Jason. I asked people to send whatever positive mojo they might have, and of course many responded in support. So many people were pulling for him. We could still hope for the best, right?

That evening I went to the grocery store. There were not a lot of shoppers, and every single person in the store was masked — with the exception of one roughneck-looking guy, probably 60-ish, in a Jack Daniels t-shirt, who walked around barefaced with a handbasket, scowling and throwing the stinkeye at everyone he encountered. I thought of all the people like him in this country at that time, casually putting themselves and others in harm’s way because their prejudices and carefully-curated ignorance had allowed their perception of a public health crisis to be manipulated into a grotesque parody of a civil liberties issue. I thought of Jason, four weeks deep in an induced coma, and I found myself getting so angry at this selfish prick that instead of saying, “Excuse me,” as I passed him in the Pop-Tarts aisle, I just almost said, “I hope someone kicks the fucking shit out of you.” Fortunately, my Buddha nature kicked in, and I instead took a deep breath and let it go.

When I got home I received word that in addition to his kidneys, Jason’s liver was failing, too. It was becoming starkly apparent that COVID19 was not something he was going to come back from.

Jason Fritts, the sweetest honeybear in the history of Wichita, died the afternoon of Monday, December 28, 2020, just a few months after his 50th birthday. The fact that he was born and lived his entire life in the most wealthy and powerful nation in the history of the world was irrelevant. This man who spread joy and love and goodwill literally everywhere he went died in no small part due to the sad fact that his personal finances prevented him from seeking prompt medical treatment for a deadly virus — that he most likely contracted while breaking quarantine in a desperate bid to scratch up a living.

Statistics indicate COVID19 mortality rate in the US is vastly greater for low-income individuals than for those who can afford timely, proper medical treatment. This is a result of multiple catastrophic failures of our government at every level — chiefly its ongoing refusal to meet modern First World standards by providing a public healthcare option to the most imperiled of its citizens.

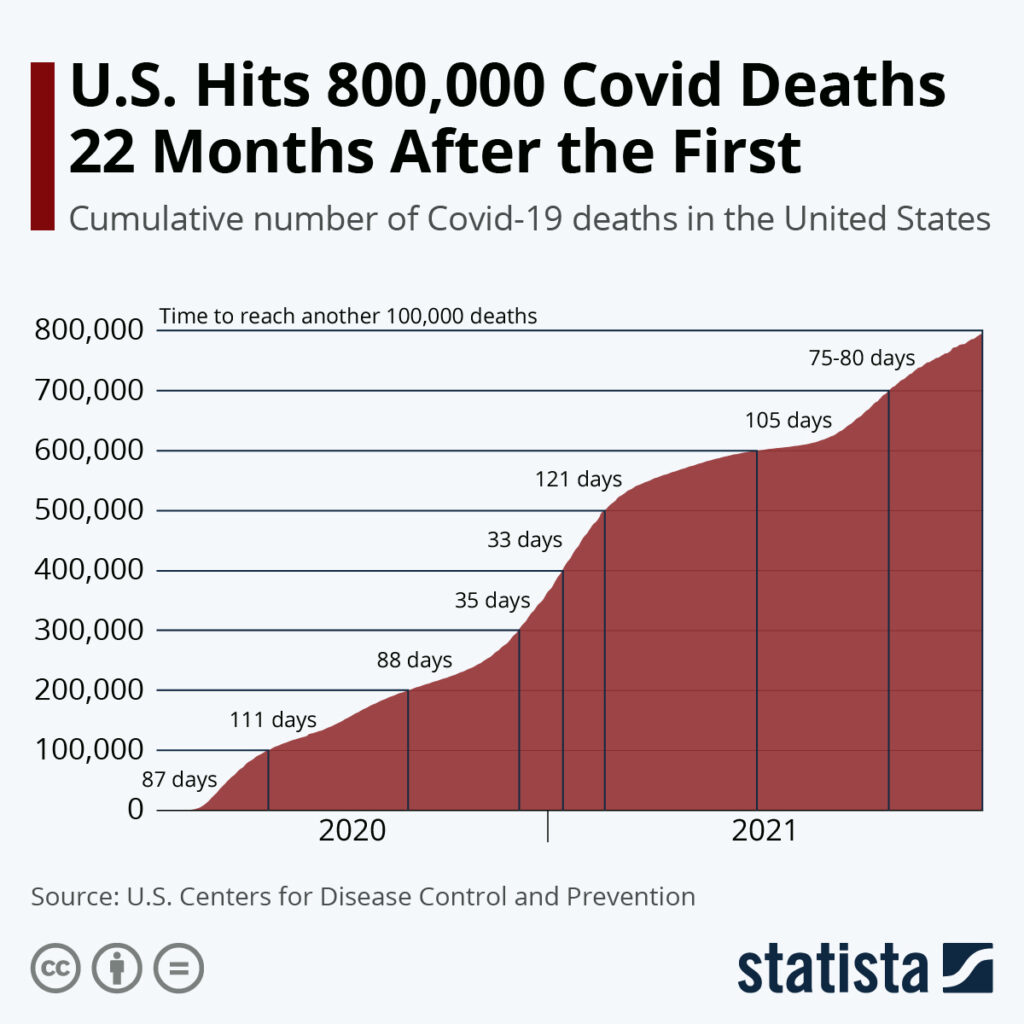

I started writing this story on Dec. 30 last year, just two days after Jason’s passing, but I was too heartbroke to publish it. At that time I wrote, “By the time this pandemic is under control there may realistically be a half-million Americans dead from COVID19 — countless among them people in positions just like Jason.”

And here we are, one year to the day after Jason left us, and the actual death toll to date in this country is just shy of 820,000 and climbing. If this horrific, preventable mass die-off of our beloved friends, family members and community touchstones isn’t enough to motivate Americans to demand — loudly and persistently — positive change for the benefit of all of this nation’s citizens, then I don’t know what is, and I shudder to imagine what this country holds in store for my children, and Jason’s child, and all of yours, too. We can do better, America. And we must.

Rest in peace, Jason Fritts. Rest assured that your memory will always be a blessing.