I have spent my entire life on the Kansas prairie, a locale as isolated from the sea as just about any to be found in the United States. But turn back the clock something like 300 million years, and the spot where I sit writing this today is submerged in the briny depths of a vast seaway connecting the Arctic Ocean with the Gulf of Mexico. Our modern continent of North America exists in this epoch as two distinct and separate landmasses — Laramidia to the west and Appalachia to the east — divided by this 2000-mile-long stretch of water. This is what we now call the Western Interior Seaway, and it will be long since gone by the time the earliest hominins appear on the planet.

Fast-forward to the 19th Century, when white settlers are first colonizing the Great Plains, seeking fortune — or in many cases just a fresh start — in the harsh, grassy wilderness. While drilling for oil in 1887, a prospector near the bustling young town of Hutchinson discovers salt instead, setting off a white gold rush of sorts, and earning Hutch the nickname “Salt City.” Eventually one name rises to the top of the viciously competitive salt game: Emerson Carey.

The legendary Kansas industrialist, son of humble farmers, had already made a considerable fortune, first in the coal business and then as a hugely successful manufacturer of ice, before getting into the salt biz in 1901. He started out using an industry-standard evaporative process in which water is pumped into and back out of subterranean salt beds, then dried to leave behind only the salt. This method produces very fine quality table salt, but yields comparatively little product for the energy and effort involved. Eventually Carey decided to stop messing around, and ordered a shaft to be dug 650 feet straight down, right into the middle of the thick bed of salt that lies below much of the region. In 1923, that goal was achieved — and raw salt has been hauled out of there by the ton, with nary a pause, ever since.

Now, I have spent plenty of time in Hutchinson, home to both the Kansas State Fairgrounds and the truly world-class air and space museum known as the Cosmosphere — yet despite my legitimate nerdly interest, somehow I had never managed to visit Strataca, the museum at the old Carey mine. Both my sons, now ages 13 and 9, had been there, but not me. They remedied that this Christmas, gifting me tickets for the deluxe tour package, and on Boxing Day afternoon, the three of us made the short drive to Hutch.

We arrived just in time to check in for our scheduled time slot, which we shared with maybe seven or eight other people. A cheerful staffer gave each of us a clip-on tag to put on our clothing, designating our group and status as full-ride ticketholders, and we each donned a hardhat, as is required to enter the mine. Our docent led us to the “hoist,” the only way in and out of the secret world so far below our feet, and we all piled into the tiny narrow car like sardines. I am not a claustrophobe by nature, but I have to admit that I had secretly harbored concern about whether I might get freaked out going down so far underground, and when we started descending into pitch darkness, I took deep a few deep, slow breaths to stave off any anxiety that might raise its head.

There is no light in the elevator car, and as we sank into the abyss, things got very dark very quickly. The docent, a woman probably in her early 20s, asked if anybody wanted a light on, and a little old abuela said, “Sí,” prompting the guide to turn on her flashlight. It was a strange sensation, dropping straight down twice the distance of the tallest building in the state of Kansas, crammed tight with strangers in this narrow little rectangular shaft, hewn from the earth a century before. During the 90-second descent, my ears felt the change in air pressure, causing mild discomfort. I alleviated this by forcing a yawn and making exaggerated chewing motions with my jaw. Note to self: If you come back here, bring gum.

And then the door slid open, and we stepped out into a big open atrium fully furnished with modern lighting and museum signage. A previous tour group was assembled there, casually waiting to be ferried back up to the surface, and as soon as we were off the lift, they were on it and away. I was caught off-guard at how strangely normal it was down there; if not for the lack of windows, we could have been in any regular building anywhere — except the walls and ceiling had clearly been cut out of the earth, with the rough edges left showing everywhere. The air was fresh, everything was professionally lighted, and there was plenty of elbow (and head) room. Throughout the rest of our three-hour visit I never once felt anxious about our surroundings.

Our docent told us the deal: We were free to walk through the whole finished museum part of the facility on a self-guided tour for an hour, and then our rides would begin. And so we began strolling. The first thing I noticed was a display featuring a snatch of a poem by one of my favorite poets, Pablo Neruda, which earned a lot of points with me right off the bat. We entered the museum through a long, wide promenade peppered with numerous well-crafted exhibits on the natural history and geology of our geographical area, and salt in general, followed by a section dedicated to the labor of the generations of miners who had toiled there, complete with vintage machinery and tools, photos, old work clothing, and even garbage (more on that later). Colorful illuminated Christmas decorations were everywhere, too, adding an extra layer of surreality to the experience.

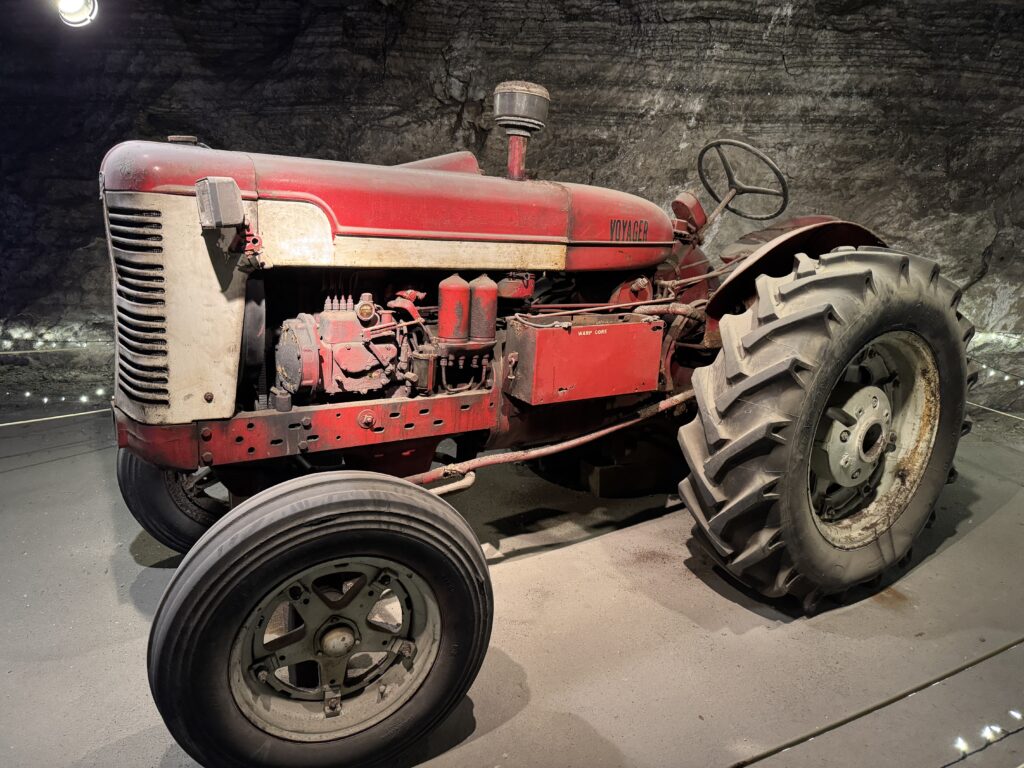

In the second area we saw an enormous implement that functioned like a chainsaw, designed to undercut walls of salt in advance of blasting, plus old tractors, various sorts of train cars, even normal old automobiles and trucks, all of which had been disassembled up above, taken down in the tiny hoist in pieces, then put back together in the mine. (The clever workers have a long history of improvising vehicles in order to get around their ever-growing subterranean maze, converting them to run on low-emission biodiesel fuel years before it became fashionable.) Some of the old retired heavy equipment on display down there has been severely eaten away from such long exposure to the corrosive effects of salt.

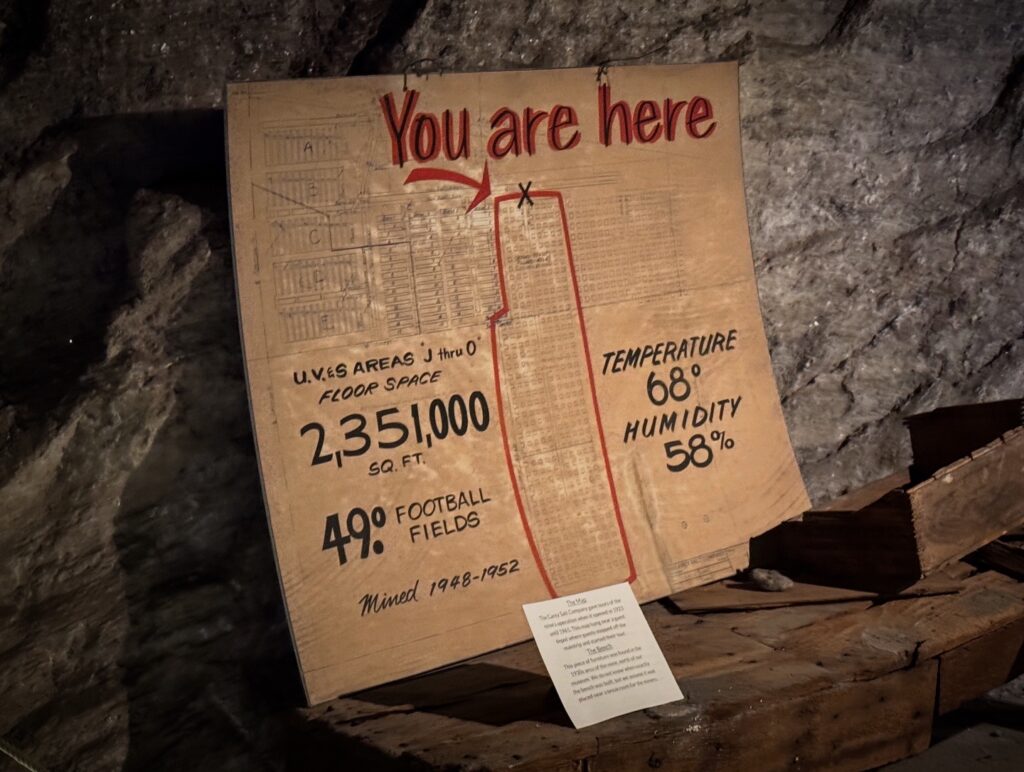

This place is still an active working mine, but we were told that the workers were actually about two miles away from our present location, and the sections of the mine we would be exploring were last worked 70 years ago, in the mid-1950s. The blasting that begins each new area of excavation takes place only at night, so there is virtually no chance of any work-related mayhem intruding on one’s visit to the museum. In fact one of our guides will later mention that in the 101-year operation of this mine, only two people have ever lost their lives onsite, both in what were simple, preventable, unfortunate accidents.

The next section of the museum is dedicated to the Cold War, the nuclear scare and the work of the Office of Civil Defense, all lifelong areas of interest to me personally as a Gen X kid. I found the displays in this part of Strataca fascinating; to be honest, I would have visited this as a standalone museum. Never have I seen such a collection of official Civil Defense supplies and equipment. They even have a little fallout shelter mockup there, vividly illustrating how small an area one could expect to be cooped up in for the duration in the event of a nuclear attack. I’m not sure it would be as charming as Donald Fagen makes it out to be.

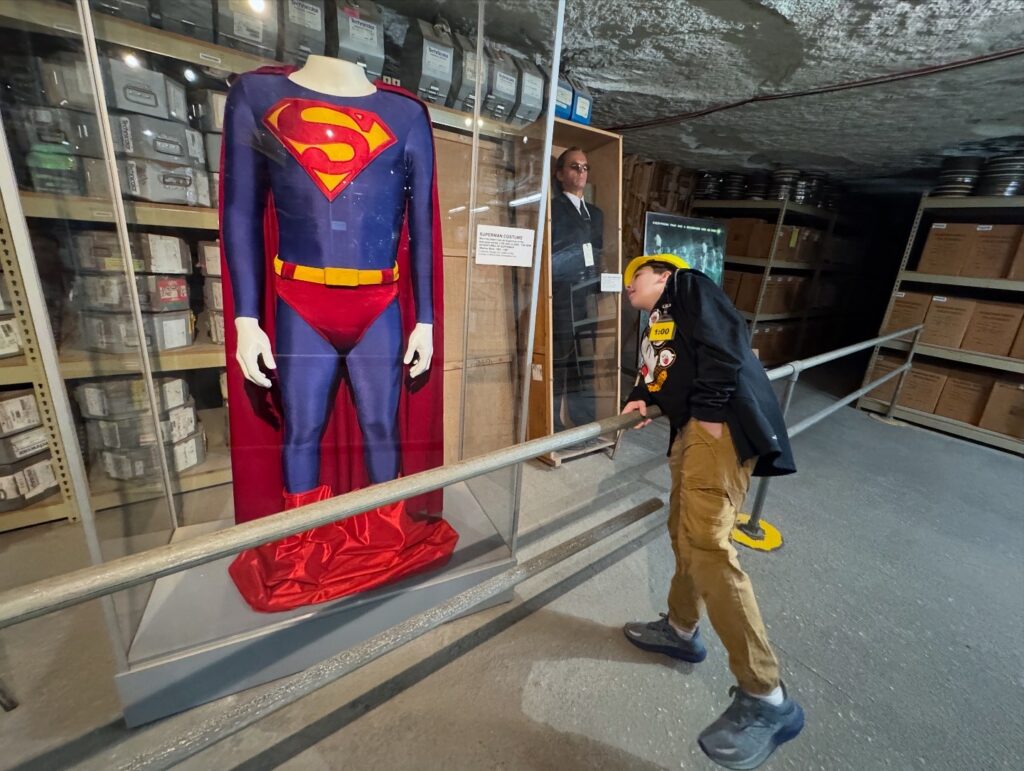

The vast caverns left behind after the extraction of salt at this depth are perfect not only for human survival in case of disaster, but also for long-term storage of all manner of important records and artifacts, and lots of interesting things are kept safe in this place — including footage and props from famous Hollywood films and television shows. The boys and I passed by shelves stacked with orderly rows of storage boxes and film cans, labeled with text such as: “Warner Bros. Television: Friends” and “Castle Rock Entertainment” and “Josh and S.A.M.: Sound Unit Inventory.” On display was a huge professional cinematic film editing bay that once was state-of-the-art but now has been rendered entirely obsolete by the digital revolution. And then we came around a corner and saw this:

That’s the actual Superman getup worn 30 years ago by actor Dean Cain on television’s Lois & Clark, and behind it you can see a highly realistic life-size mannequin of Hugo Weaving, dressed in his role as Agent Smith in the Matrix movies. This particular dummy was one of 20 used in backgrounds of scenes in 2003’s Matrix Revolutions. Just a few feet away were displays with costumes worn by Will Ferrell and Sascha Baron Cohen in Talladega Nights and George Clooney and Arnold Schwarzenegger in Batman and Robin.

Once we passed through the Hollywood storage displays, we found ourselves in the gift shop and snack bar. Here we were told that the first of our three rides — the Salt Safari — would be departing in about 15 minutes, and we took the opportunity to drink a bottle of water and use the bathroom. I availed myself of the tiny little wifi bubble to be had only in that zone, checking my phone and making one last Facebook post before plunging into the deep dark recesses of the mine.

As our electric tram was just about to start boarding, my sons, having visited before, advised me to sit near the front, in order to better hear the spiel of the guide as he drove. I did as they suggested, and we (along with the pleasant middle-aged fellow who sat next to me) took up the two front rows of seats. Before we took off, our guide, a friendly older gentleman, gave each of us a small but quite powerful LED flashlight and told us there was no lighting where we were going, and each of us would be responsible for doing our part to illuminate the journey.

And then the tram pulled forward, leaving the modern comforts of the gift shop behind as we plunged into the void.

The first thing that got to me was the scale of the thing. The salt here has been methodically carved out in a process called “room and pillar” mining, in which large rectangular “rooms” are blasted out and cut to precise measurements, leaving behind a checkerboard-like grid of support pillars forty feet square to hold up the untold tons of earth above. Long corridors, once serviced by rail cars on movable temporary railroad tracks, connect these rooms, each its own yawning empty space receding into the darkness. Reportedly if you put all these chambers end to end, they would stretch more than 150 miles.

Our guide did a wonderful job highlighting and explaining various points of interest over the course of the hour-long Salt Safari, including abandoned remnants of old electrical wiring junctions, places where ceilings had collapsed or floors had buckled upward, interesting geological formations — and weirdly, just so much old trash. Though nobody had done any mining work in this part of the facility since Eisenhower was in office, everything that had been brought down the hoist by the miners then was still down there.

“After all,” our driver asked by way of explanation, “what’s the use in taking your trash back up to the surface, then hauling it somewhere else to be buried in a different hole in the ground?”

We saw in numerous locations literally hundreds of cardboard dynamite boxes, some stacked neatly, others strewn carelessly. Most eye-popping was one particular corner of a pillar that had evidently been designated a dump site by the workers, as there was a sea of food wrappers, paper water cones, light bulb boxes and other garbage — all of it looking just about as fresh as the day it had been dropped there.

And then there were the tire tracks and human boot prints off in some of the side rooms, made more than a decade before I was born, destined to be there still thousands of years after I am dead, just like those of the Apollo astronauts on the moon. All of this, coupled with my sense of being in an environment hostile to sustaining human life, led me over and over to think of this trip beneath the earth as an analog to space travel. My insignificance in the grand scheme of the cosmos — long a source of comfort rather than dread to me, thanks to my history of hallucinogen use and Buddhist practice — was emphasized here in a very big way, and I had never felt more present in a moment in my life.

The Cosmosphere has outer space covered; this place is devoted to the exploration of inner space.

At just about the farthest depths of the tram ride, the driver stopped and asked us all to extinguish our flashlights and sit quietly for a minute in what he called “mine dark.” My experience of this is hard to describe, but I can imagine it must be at least somewhat akin to that of floating in a sensory deprivation tank. The absence of light, of sound, overwhelms the senses until it becomes a physical sensation, the very space around a person seeming to constrict and compress, the whine of blood flowing in the ears growing in volume to fill up the silence. After some seconds passed I heard murmurs of discomfort from some of the passengers behind us on the tram, and the guide mercifully instructed us to turn our flashlights back on. I can’t say I wasn’t relieved.

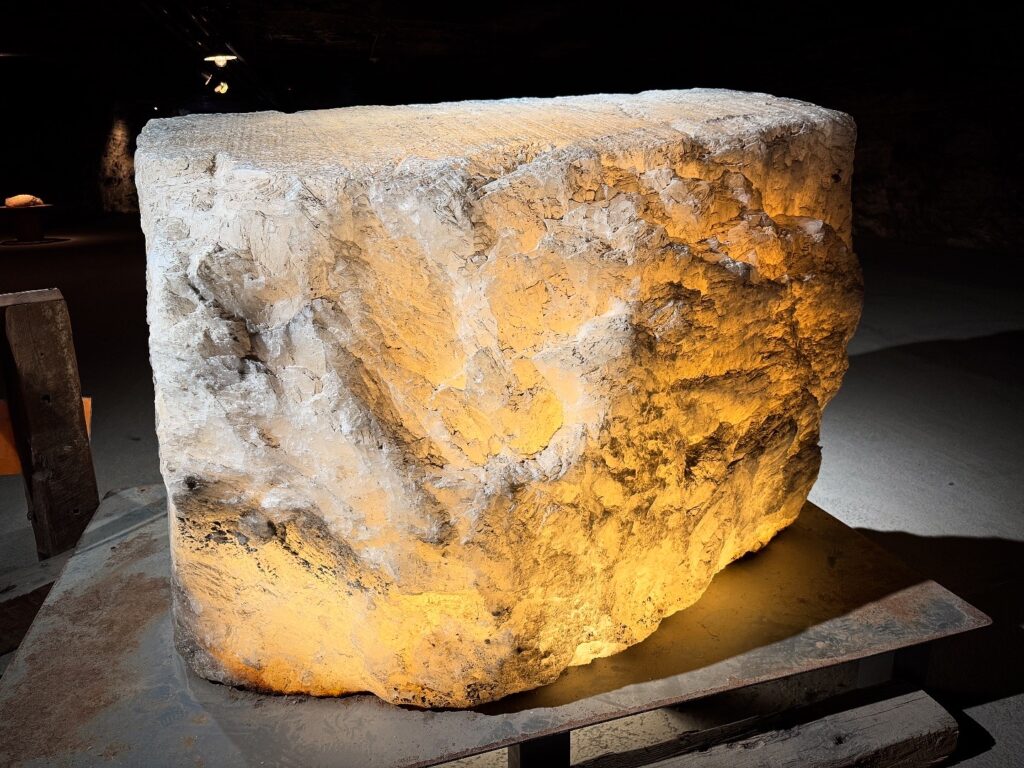

Around this time, we were also given our only opportunity to step off the tram, next to a big pile of excavated chunks of raw salt. As part of the Salt Safari, we were each allowed to take home one piece as a souvenir — provided it was no bigger than the hardhat left at the site for just such measurement purposes. I took the opportunity to stretch my legs, walking a few yards away from the tram and my fellow passengers, now all milling about and poking through the salt rubble on the floor, each hunting for their own keepsake. I sang low into the receding blackness an old Merle Travis line: “It’s dark as a dungeon way down in the mine” — and the tune disappeared into the saline depths without a trace. Before I got back into my seat, I grabbed a nice looking piece of ore, and I held onto it like a diamond through the rest of the whole trip. The boys each got one of their own, too.

After that, the tram started making its way back up to the lobby, with a few more educational interjections by our guide. As we re-entered the warm glow of the finished section, the tram took a left, and we passed through a heavily Christmased area of the museum, then returned to the spot where we had started. The last thing our driver told us was that Strataca regularly hosts a 5K/10K run, murder mystery party events, and even sleepovers for Scout groups. I would have thought that was the coolest thing in the world when I was a kid!

As deluxe ticketholders we still had two rides left, each much shorter in duration than the Salt Safari. As fate would have it, the boys and I would be the only passengers on both. The first was the train ride, which is just what it sounds like — a ride on fixed rails in a cute miniature amusement park train. This one is mostly a joyride, but once again, I was thrilled to be whisked around the silent, ghostly halls of the mine, taking a new path, seeing things from another perspective.

And then came the “dark ride,” during which passengers do not have flashlights. The driver takes a (mostly) different route than the Salt Safari, with the long black passages punctuated by stops at spotlit exhibits of artifacts highlighting various aspects of the mining operation. Though this mini-tour touched on some of the same information covered earlier, I still found it interesting and enlightening (no pun intended.)

And then we were finished with our visit. We passed back through the grand hallway where we had first entered, then stood waiting at the hoist with a sizable group of others ready to return to the surface. There were too many for one single elevator car, and that’s when I learned that there are actually two cars on this rig — one stacked directly on top of the other. We watched as a bunch of people piled in, then the lift went up about seven or eight feet, stopped — and a second door opened, allowing us into the bottom car. As strange as it had been coming down, it felt extra crazy going back up, knowing that there were people just about a foot above our heads in the same shaft. (I couldn’t help but think of the shift changes depicted in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.) Once we finally reached the surface, we had to wait just below floor level while the guests in the top car disembarked, and then the hoist was raised so that we could get out, too. We ditched our hardhats and were out the door.

As we walked to our car in the parking lot, I put my arms around both my sons and thanked them once again for bringing me to this amazing place. They certainly know their old man well. I can’t think of a gift I have received in ages that so totally blew my mind, and to be honest, I couldn’t get the experience off my mind for days afterward. It was truly a top-shelf Dad & Lad adventure for the books — and words fail to adequately stress how strongly I recommend that you, dear reader, take the opportunity to check it out for yourself.

Back at home, I gently cleaned my souvenir chunk of salt ore just as our guide had advised, and I held it up to the winter afternoon sunlight streaming through my western window. Iron and other mineral impurities may render this salt unsuitable for use on the dinner table, but they sure add spectacular dimensions of depth and brilliant color. (Yes, of course I gave it a little lick — and yes, it is quite salty.)

I look at this lovely thing and think about how for 300 million years it was just a tiny indistinguishable fragment of mineral buried deep beneath the soil, and then someone knocked it loose, and later on, I picked it up and brought it home. Barring anything happening to it, this crystalline object will certainly outlive me, and maybe if fortune smiles on it, one of my sons’ descendants will still have it on display in their home long, long after I am gone.

Maybe they will love Neruda too:

In its caves

the salt moans, mountain

of buried light,

translucent cathedral,

crystal of the sea, oblivion

of the waves.

And then on every table

in the world,

salt,

we see your piquant

powder

sprinkling

vital light

upon

our food...

…In it, we taste infinitude.