Everything in this story is true. Some names may be changed for the usual reasons.

My Grandpa Troy retired from 40 years on the Santa Fe Railroad in 1979, and before the ink on his lifetime service certificate had time to dry, he and my grandmother suddenly found themselves tasked with taking care of me and my younger brother full-time. Troy was barely into his 60s, though to me he seemed like an old man, and it was plain, though unspoken, that he was a little resentful of being saddled with this responsibility in what was supposed to be his golden years. To his credit, he did his best to engage us and involve us in outside activities he thought would be good for us.

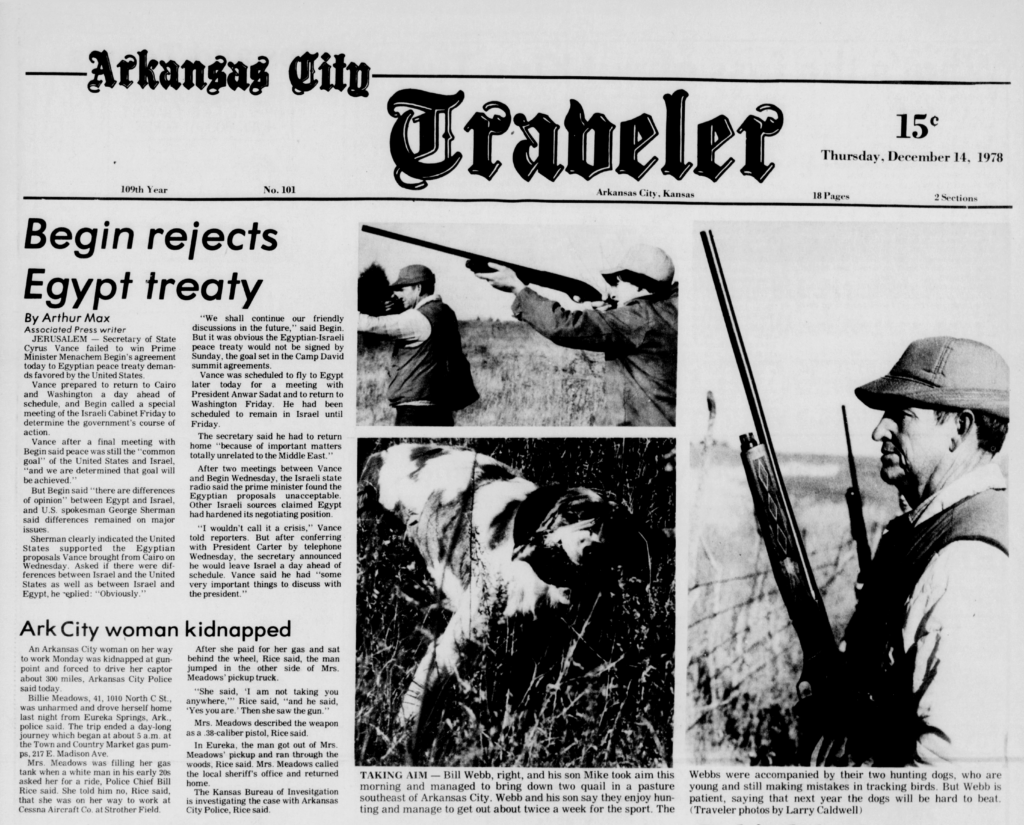

As secretary of the men’s league at our local bowling alley, Troy got me into a youth league that rolled competitively every Saturday morning, while my little brother Chris opted for more vigorous sports like soccer and basketball, both of which were offered by our small rural hometown’s department of recreation. And as another push in the right direction for me, not long after I turned 12 in December 1980, my grandfather suggested I try to get on as a paperboy for our city newspaper, the Arkansas City Daily Traveler.

As luck would have it, a route was just about to come open, not terribly far from our house. To be honest I don’t remember how I officially landed the gig, but I recall clearly the first day I showed up for training. The carrier I was to replace was a kid named Jeff, a couple years older than me, whose own house was actually within that route. He was both friendly enough and smart enough to do a good job teaching me everything I needed to know about the job, which included not only delivering papers, but also collecting the money each month for customers’ subscription fees.

That last part gave me pause at first, as it seemed like it bore the seeds for a lot of potential confrontation with adults — and given my personal history with my mother and stepfather, that was something I wished to avoid. But the majority of customers on Route 27B were elderly retirees and comfortable middle-class working families, and I saw that the previous paperboy seemed to have an easy rapport with most everyone who came to the door when we knocked on collection rounds. By the time I officially took the reins, he had personally introduced me to nearly every householder on the run.

In those days the Traveler was published six days a week with no Sunday edition. (Many locals subcribed to Sunday-only delivery of the Wichita Eagle & Beacon, the Tulsa World or the Oklahoma City Oklahoman to round out their weekly print news diet.) Monday through Friday the Traveler came out in the afternoon; on Saturdays it was delivered first thing in the morning. This meant during the week I went to school as usual, then came home and waited for the newspaper van to stop out front and throw the day’s bundle of papers out onto the lawn. I would fetch the heavy stack — or sometimes stacks, if it was an edition with more pages than usual — into the house, cut the rough nylon twine that held them together, then start the rolling process.

A flat, open newspaper of course cannot be thrown any distance with accuracy, and is subject to coming apart and blowing away in the eternal Kansas wind, so each individual paper I delivered had to first be rolled into a tight baton, then secured with a rubber band double or trebled on itself, depending on the girth of that day’s edition. If it even looked like the weather might get damp, we were supposed to slip the paper inside a brightly-colored disposable plastic rain sleeve, too. (We had to buy our own rubber bands and rain sleeves from the circulation manager, but they came in bulk, and were reasonably inexpensive.)

Just writing about this right now I find myself overwhelmed with the memory of the smell of that old grimy petroleum-based ink, which permeated my palms and fingers so thoroughly that I never really had entirely clean hands the entire four years I delivered the Traveler. By the end of the ’80s most commercial presses would replace these inks with vegetable-based alternatives, rendering this phenomenon a thing of the past, along with the ability to capture cartoon images from the paper using Silly Putty. The daily news didn’t even smell like solvent anymore.

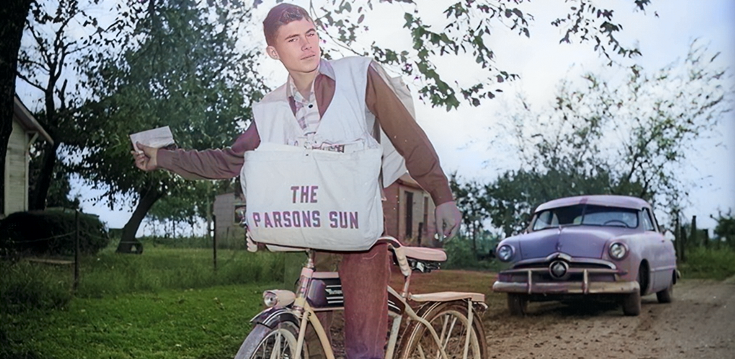

Once the whole pile of papers was rolled and ready to go, I would load them into the front and aft pockets of the giant over-the-shoulder delivery bag provided by the newspaper office, hop on my bicycle, and go run the route. (On Saturdays all this occurred first thing in the morning, which eventually put a stop to my youth bowling career, as our lane times clashed with the expectations of my customers. I often groused about the necessity of the Saturday edition altogether, as on many occasions it barely amounted to a scant eight pages of leftover news and advertising, hardly worth getting out of bed for.)

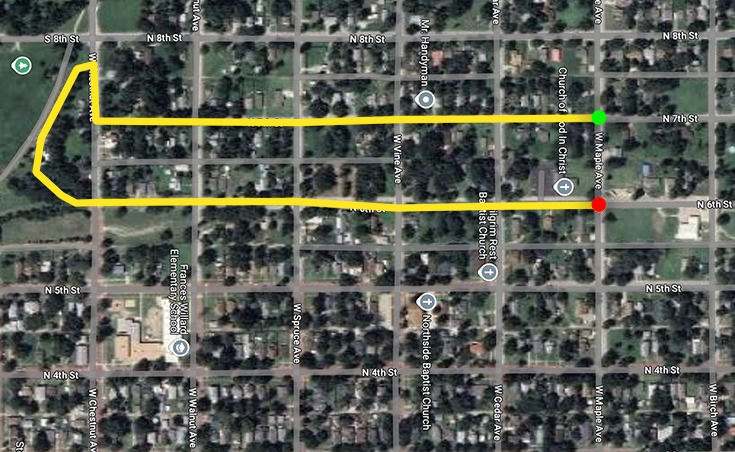

27B was made up of six residential blocks just off our town’s main drag, plus an apartment complex at the tail end. The first house was about three-quarters of a mile from my own, so it only took me about five minutes or so to get started once I left home, longer if the weather made things difficult. (And believe me, it often did.) I delivered about 80 newspapers a day, which took me on average maybe 30 minutes, plus the ride back home.

I would zip down the two blocks of First Street, ride across the earthen dike of the drainage canal at the north edge of my route, then back to Kansas Avenue on Second, then north once again up Third, finishing up with a circuit of the tony brick Parman Lane Apartments.

At first I had to take along my little subscription flipbook to remember which houses were my current customers and which weren’t, but I was a quick study, and it only took maybe a week before I had this down pat. To be fair, almost every house took the paper, and it wasn’t that tough to remember the handful that didn’t, though sometimes a new renter might pop up, gaining or losing me a customer at a particular address.

A bigger part of the lore for any given route was the location where each customer wished to find their paper. Many were fine with it just being tossed onto the porch, but some had curb mailboxes with an extra little port for the newspaper — as we were disallowed from putting them in official U.S. Mail receptacles. One old timer had a homemade combination mail/newspaper box on a pole next to the street, complete with a metal flag that he asked me to raise when I made my delivery, so he could look out the window and see when the paper had arrived. Others had slots next to, or actual cut into, their front doors, and expected me to walk up and deposit the paper therein on the daily, and in those cases, I did.

With practice I got very good at placement, getting most every paper right up to the front door of its corresponding house without stopping the bicycle. I even won a prize for this skill once at one of the summertime “paperboy rodeo” events hosted as a treat for the delivery crew by our circulation manager, an energetic and bright-eyed fellow named (I think?) Richard, whose premature baldness belied his youth. These rodeos were cookouts in a local park and included competitions between the paperboys to show off their skills, among them the ability to toss a paper precisely into a small cardboard box from a distance on a moving bicycle. Here, being celebrated for my work with these other guys roughly my age — and yes, just about every one of them was a guy — I experienced one of my earliest brushes with working class camaraderie. Grandpa Troy was right: This was good for me.

Not to mention I was making my own money for the first time! I mean, it wasn’t much money, but when you are 12 or 13 and eat for free and have no bills, any money seems like a lot. Before long I fell down the music nerd rabbit hole (for life, it turned out), haunting the record sections of our town’s K-Mart, TG&Y, F.W. Woolworth and mom-n-pop Sparks Music stores, and spending most of my paper route money on seven-inch singles and cassettes of the latest album releases. I saved up for a Super 8 movie camera and projector set I saw in the Sears catalog. And I upgraded bicycles — and Walkman knockoffs — a couple times, too, both of which I could rationalize as equipment concessions to the demands of my paper route.

But to get the money, I first had to collect it from my customers. So on the first of every month, after I delivered that evening’s paper, I would go home, eat dinner, then head back over to 27B — carrying my grandpa’s old railroad lantern against the dark in winter months — and start knocking on doors. Most of my clientele were pleasant to deal with, and they would either pull cash out of a wallet or purse, or have me stand there while they wrote a personal check for $3.47, the monthly rate at the time I started working for the Traveler. (Additionally, my first set of rounds became a crash course in how to count change back quickly and correctly, as the old timers on my route expected nothing less.) Sometimes I would be invited inside for a minute, and I always keen to have a little sneak peek inside these people’s houses and lives.

Then there were the customers who dodged me when I knocked. I remember going to collect at a specific house that had just started a subscription the month before. I had never seen anybody at this address, though there were cars in the driveway, and when I walked up onto the porch for the very first time, I was surprised, amused and a little bit alarmed to see a DYMO labelmaker sticker stuck on the glass at just about adult eye level, reading:

I could hear the high-pitched whine of an old CRT television set coming from inside the house, but even after knocking three times, I got no reply. I went back several times later to collect from this person but never succeeded. At the end of the month I was told to stop delivering there. But this was not par for the course at all; most of my customers were genuinely decent people and made my job easier. In fact I became downright friendly with a lot of them.

On that note, I quickly noticed that there were what seemed like an inordinate number of homes on my route in which fully adult, even middle aged, people with developmental disabilities lived with their even older parents. I never did figure out why so many folks in this demographic happened to live on the same couple of blocks, and it felt like an awkward question to ask, so I didn’t. I started becoming aware of this during my very first week on the job, when a grey-haired fellow sprinted out the front door of his house toward me on my bike.

“Jeff! Jeff!” he shouted at me. That had been the previous paperboy’s name, so I assumed this gentleman was mistaking me for that kid. I stopped to see what he wanted.

The man ran right up to the curb where I stood straddling my bike, suddenly stopping short just when I thought he was about to plow right into me. Once he was up close I quickly deduced from his manner that he was probably not the man of the house.

“Hi,” I said as he panted and slouched, his head cocked down and to the side in the manner of a bird. It appeared he was beside himself with excitement to see me and yet afraid to make eye contact. “I’m not Jeff, though, I’m the new paperboy, my name is Michael.”

“Do you remember that time when Jeff shot that squirrel with the BB gun!?” he blurted out, loud, a naughty half-smile blooming on his mouth. I didn’t know how to respond.

“Jeff, he shot that squirrel, remember? With the BB gun?” he asked again, taking a half-step closer to me.

I was weighted down by nearly my full load of papers, as his house was one of the first on my route, and growing more uncomfortable by the second.

“Do you mean Jeff, the old paperboy who lives around the corner?” I asked, trying to be helpful. “I am taking over for him now, he isn’t delivering the paper anymore.”

The door of the house suddenly opened behind the curious fellow and a white-haired pensioner emerged and hurried across the yard toward us. The man gently put his hands on his son’s shoulders and asked him to go back inside the house, and the younger fellow turned without a word and did just that.

“I’m so sorry,” the old man said. “My son is easily excited. He’s harmless, I promise, but he will talk your ear off if you let him. Don’t feel bad about waving and just going on with your business, I know you have a lot of papers to throw.”

“It’s no problem at all,” I replied. “I think he thought I was Jeff, the paperboy from before. He said something about him shooting a squirrel with a BB gun?”

A moment of surprise flashed in the man’s eyes, followed by a warm chortle and a slight shaking of the head from side to side.

“Oh goodness,” he said, “he’s talking about something that happened way back in the ’60s, likely before you were born, son. I don’t know what compelled him to run out and tell you about it.”

It would not be the last time I let his son waylay me at the curb. He just seemed so genuinely ecstatic to catch me, and I felt bad if I didn’t let him express himself a little bit. Eventually I learned how to taper off our interactions smoothly so I could keep moving without feeling like I was hurting his feelings.

On the same block was a young man in his twenties who I met while running my evening collection rounds for the first time. He answered the door at his parents’ house and when I told him what I was there for, rather than fetching his mom or dad, he earnestly stuck out his hand for a shake and said, “Hi, my name is Paul Thomas, do you like to shoot pool?”

Paul Thomas (he used both his first and middle names at all times) clearly had some form of intellectual disability, but was what I suppose you would call “high functioning,” and in fact quite a funny and sociable chap. We became kind of buddies for a while. Later on I did meet him at the bowling alley a few times for billiards and video games, and on one memorable occasion I helped him sell Tootsie Rolls on the sidewalk in front of Woolworth’s downtown to raise money for the Knights of Columbus. I wonder whatever happened to him.

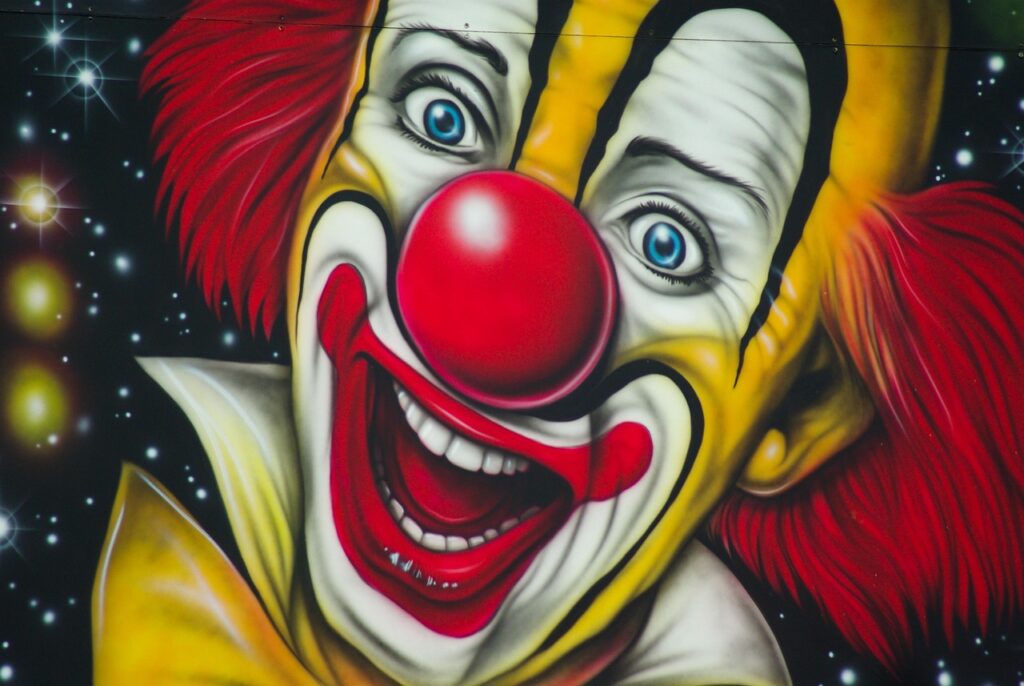

I am horrified just now to have reminded myself that on that same block lived a mild-mannered woman of maybe 50 who always paid by check. For probably the first year I ran this route, every time I saw her up close I thought there was something strange about her face, but I could never quite figure it out. Then one day she came to the door without any makeup on and I realized that she had no eyebrows at all, and this whole time she had been drawing them on. Another time she came to the door in FULL CLOWN REGALIA — with no acknowledgement or explanation whatsoever. I stood there in stunned consternation for probably two solid minutes while she fetched her checkbook and a pen, then wrote me a check and filled in the info in her ledger, all the time in full whiteface makeup, red nose, frizzy fright wig, crazy rainbow-colored outfit, giant floppy shoes, the whole bit. She never said a word about it, nor did I ask.

At least half my route was made up of retirees, some of them getting to be quite old, people who were born in the 19th century even. A lot of them knew my grandparents, and offered condolences when Grandpa Troy died suddenly in February of 1982. I would see them out puttering in their flowerbeds or working to make their yards into showplaces of concrete ornaments, though others were too frail to do much of anything but wait for their clocks to run out. There was a gent on one block who owned an Amphicar, a 1960s convertible automobile that could be driven into water and used as a boat; I wanted to ask him about it but his wife always answered the door when I knocked. Eventually came the occasion when I was invited into the house, and discovered that the man of the house was laid up in a hospital bed in the living room, and evidently had been for quite some time. I didn’t ask about the car.

My customers often asked me for a hand with things around their houses, and I was forever powerless to decline. I provided assistance with all kinds of things — digging holes for flower bulbs, reaching up for objects that had been put away years before on high shelves, schlepping garbage and leaf bags out to the curb, rearranging furniture, squaring up boat trailers on the hitches of pickup trucks, whatever anybody needed help with. I didn’t do any of this for brownie points; I just had this deep and genuine desire to feel useful to anyone, and giving Old Mrs. Clay a hand carrying in an ottoman from the trunk of her car really did give me the sense that my existence was at least a little justified.

But my Boy Scout nature paid off in spades at holiday time, when my loyal customers would load me up with homemade fudge, cookies, popcorn balls and other old-timey goodies — not to mention the many Christmas cards I received upon making collection rounds the first of December each year, most of them with at least a couple dollars inside. By my second Christmas I was receiving what seemed like a staggering number of five-dollar bills as year-end tips, and it really made me feel like I must be doing a good job.

And that’s the thing about being a paperboy: For all the getting up early on Saturday mornings, the ink stains on everything I touched, the absolutely miserable vagaries of Kansas weather, the challenges of aggressive dogs, the daily time commitment, all the downsides — at the end of the day I felt in my heart like I was providing a valuable service for the people in my community, and they appreciated the fact that I took care to do it right. I don’t know that a kid can do much better.

Eventually I got the opportunity to take a different route, much closer to home; in fact, it started only about three blocks down the road from my grandma’s house. By this time the paper had gone over pretty much entirely to a pay-at-the-office subscription policy, and I was no longer required to collect from the customers, so I wasn’t knocking on everybody’s door once a month anymore. I broke the news of my departure and said goodbye to those customers I happened to catch outside in my last weeks as their delivery boy, and it was clear that some of them were really going to miss me. The feeling was mutual.

The fact that I cannot today remember the number of the paper route I took over is perhaps not so surprising given the changing nature of the job and my relationship to it. My emancipation from monthly collection runs was most welcome, but it had the side effect of distancing me from my customers. I rarely had cause to knock on anybody’s door or speak face-to-face with them, and I threw the paper to many houses where I never saw the residents inside at all. I had no idea who they were outside their name and address on my route sheet. The vibe was markedly different.

The neighborhood was different, too, with more empty lots and rental properties, where it seemed people were less likely to subscribe to the paper. My route covered much of what had been historically one of the Blacker areas of town, right along the old Frisco tracks, by this time disused for a decade or more. I even delivered to the rather legendary Black juke joint called the Grand Terrace, sandwiched between Sixth and Seventh on Maple Street at one end of my route. (That place is a story someone ought to write.) My customer base here, as on 27B before it, was starting to age out, too.

Looking back now I am struck at how sharply I remember every detail of my first route, and by comparison so little of the second. I can think of countless individual incidents and interactions that took place on 27B, but just about literally the only highlights I recall from the later route are the time I saw a woodpecker up close, and finding a copy of The Yes Album at a garage sale for a quarter. The rest is kind of a blur.

Of course, this was also the time when I was getting interested in cars and girls and playing the guitar, and the amount I was getting paid to do the paper route seemed less and less like enough to warrant sustaining the effort. I turned 16 in December of 1984, and a few months later my grandmother bought me my first car on the condition that I pay for the insurance, gas and upkeep. Finally being old enough to get a more grown-up gig, I hung up my delivery satchel and tied on an apron at Long John Silver’s.

My paperboy career lasted only half as long as the Reagan Era, but the experience really did stick with me, and to this day I lean on the many life lessons I picked up in those four years of awkward adolescence, when I served the good citizens of my hometown as faithful courier of the daily news.

Now it’s 2025 and the paperboy on a bicycle, an absolute icon of Americana, is a thing of the past too. Newspapers today survive mostly on the internet, with 74% of people polled by Pew Research in 2024 saying they never or rarely read news in an actual physical edition of a daily or Sunday paper. Not only are home subscriptions for print publications in the toilet, there’s also the fact that modern sensibilities regarding unsupervised minors running the streets doing child labor have put the kibosh on the whole delivery methodology.

These changing social trends have triggered a mass extinction among small town papers nationwide, and even the Traveler might not have survived had it not merged with the Winfield Courier, published for more than a century in the next town over; now known as the Cowley Courier Traveler, this publication covers news all over Cowley County, and is printed — on paper — three times a week.

Area subscribers get their copies the next day in the mail.

Great story Michael! Of course, I relate to this on a very deep level having been your substitute delivery boy many times and then eventually taking over the route you vacated for three years. Of course my greatest memory is going along with you on that first route and heading in to Big Cheese Pizza to hit the arcade (best arcade in town!). I remember you knowing when the guy would come around to collect the quarters and if we were there he’d give us free plays…

Oh man yes, I remember it very well! That little cool, dark back room with the video games was like an opium den for adolescent boys!

Been there, done that. Except I had graduated to semi-novice driver and was peddling copies of the Tulsa World at 4:30 a.m. Today my 9-5 is still the world of newsprint. Just imagine…

(BTW you won’t find me on Farcebook anymore. Look for the tax collector where the sky is blue.)

Right on. The biz has changed a lot, yet manages to hang on.