This really happened. Names, details of some events and some identifying factors have been changed for the usual reasons.

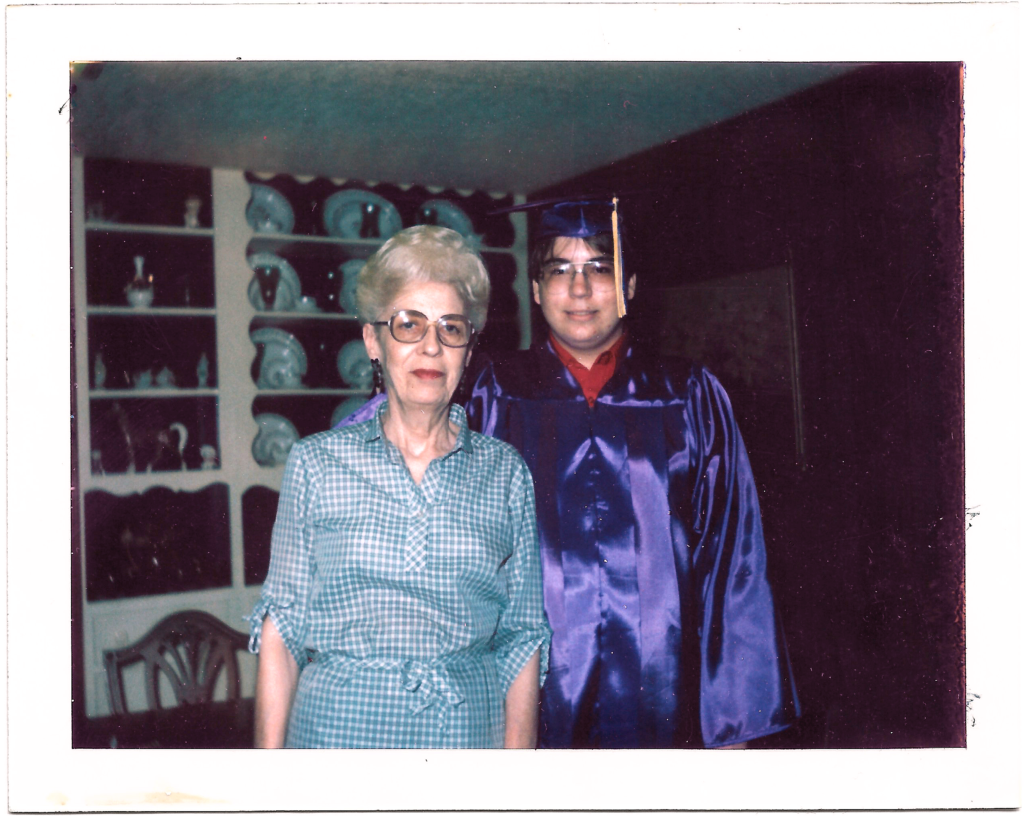

Despite my dismal grades and worse attitude, I was allowed in May of 1987 to graduate from high school. I basked in the intoxicating sense of emancipation which overcame me, knowing I would never have to set foot in that spirit-hobbling hall of horrors again — but the bigger question of what I might do next became more pressing by the day.

A new budget motor hotel had been built on the north edge of town, and I worked a brief temp job in one of its suites, which had been converted temporarily into a makeshift telemarketing boiler room. My job was to make cold calls to people in my small rural hometown and the next town over and try to talk them into scheduling a family portrait session with Olan Mills, who were not only the nation’s most well-known photographers, but also, I was proudly informed, phone sales pioneers. I would sit for four hours at a stretch in the evenings, going through the list of names and numbers and making the same pitch over and over, only occasionally managing to book an appointment. The pay was $3.35 an hour, plus small bonuses for reaching certain sales goals. I don’t recall earning any of the bonuses.

Every minute in there felt like an hour. The in-room AC units were loud so they kept them turned off most of the time, causing me to sweat prolifically into my cloth-covered padded office chair. The door to the hallway would open occasionally and the chlorine smell from the hotel’s indoor pool would waft in and it was all I could do not to put down the handset and walk out into the atrium and jump into the clean blue water. But I knew this gig would only last a couple weeks, and I hung with it for the paycheck.

Someone told me the local job board was administering vocational aptitude tests at the VFW Hall just down the main drag from the hotel. If one did well on these tests, it could help land a steady gig at any of the numerous manufacturing plants in the county. I happened to be a natural test-taker, and registered to attend a session. I am not sure what I had expected, but I was a little distressed to find a significant percentage of the testing measured not intellectual, but physical, abilities. I did pretty well on the manual dexterity segment, which involved several tasks such as pulling bolts out of holes with both hands and putting them into other holes quickly and efficiently; I did much worse on the digital dexterity portion, which required me to pick up tiny individual washers from rods and move them to others in the same manner. My hands were good; my fingers not so much. I didn’t see much of a future for me in factory work anyway, I supposed — but looking around my town, I saw lots of folks making good livings at it, so the prospect was never far from my mind.

At this time my younger brother and I were still living with my grandmother and her ancient Okie father. It had been five years since my grandfather had suddenly died, and though the transition had been rough, the four of us had settled into something resembling a functional family unit. Also I was still dating my first proper girlfriend, the unpredictable Marya (pronounced Maria, spelling changed as an affectation), who had graduated the year before and already had one year of community college under her belt. I was looking forward to joining her in the journalism department there in the fall, but still had a whole summer to fill up — and I needed some income badly.

One afternoon Marya came by the house and told me she had found herself a new job, and she was sure there was a position for me, too. I asked her what kind of work it was.

“Selling Kirby vacuum cleaners door-to-door,” she replied. I was taken aback.

“They still do that!?”

Before I knew what was happening, I was putting on a clean button-up shirt and the nicer of my two pairs of jeans and driving downtown to the ramshackle storefront that housed the local Kirby sales office, where I had a meeting with a pair of gentlemen named Bill and Fred. Both of them were middle-aged and white, but differed vastly in vibe. Fred had a non-threateningly smarmy Herb Tarlek thing going on; though he was dressed in nondescript casual office attire, he wore his dark, lazily-curly hair a little long in the back, and a flashy gold watch glinted on his wrist. Bill, the top dog of the local organization, appeared something of a man out of time — imagine how Ron Swanson might have looked in 1975, impeccably groomed with a mustache and Gerald Ford-era haircut, dressed professionally in a tie and short-sleeved dress shirt tucked into neatly-pressed slacks. He was a big man, built like a linebacker, but charismatic and handsome and he smelled good — a natural salesman.

They were clearly eager to welcome me aboard, and our meeting was upbeat and perfunctory. I signed on as an independent contractor and there were handshakes and huzzahs all around. I was then escorted into the back room of the place, a low-ceilinged, fluorescent-lit jumble of boxes and metal folding chairs and dead dirty styrofoam coffee cups and overfull ashtrays, where I was introduced to Frosty, the old World War II vet who I was told came in a few times a week to renovate traded-in Kirbys for resale there in the office. In his powder-blue speedsuit, he reminded me of a couple of my salty great-uncles, and when he clenched his cigarette in his mouth and reached out and shook my hand, he nearly crushed it.

Bill sat me down in front of a rolling A/V cart and played me a video on the history of the Kirby company. This is in and of itself a pretty interesting tale of American industry, the short version of which is that a clever engineer named James B. Kirby — inventor of the revolutionary washing machine spin cycle — designed some of the first truly efficacious electric vacuum cleaners, and teamed up after World War I with a pair of industrialists to launch the iconic Kirby line of luxury-tier machines, which has ever since been sold and supported in the field by a vast network of regional hubs and their attendant crews of tireless peddlers.

By the time the video was done, I found that the only other person left in the office was Fred. He came back and shut off the TV.

“Sorry to cut this short, but I’ve gotta shut her down for the afternoon,” he said, looking at his watch. He handed me an unmarked VHS cartridge. “You and your lady watch this tonight, all right?” I agreed and he briskly walked me to the front entrance, shutting off the lights and locking the door behind both of us. There was something about this guy I just couldn’t put my finger on. I had already noted his habit of making little joking comments — not all of them nice, and most not what we’d call “PC” today — followed by a cartoonish heh heh heh. He was nice enough anyway, I guessed. Maybe I’d like him better when I got to know him a little.

I drove home and called Marya, who agreed to come over after dinnertime that evening to watch the training tape. I had a little 13″ Zenith color TV and a VCR in my bedroom, and when the time came, I popped the tape in, and the two of us sat down on my bed to watch. Much to our surprise, what came up on the screen was not a Kirby sales training presentation at all.

It was in fact a home-dubbed copy of a hardcore porno film. Neither Marya nor I were strangers to dirty movies, but we sure didn’t expect to see full-on explicit anal instead of helpful tips on selling vacuum cleaners. When I returned the tape to Bill the next day and explained the situation, he apologized sheepishly.

“You gotta watch that damn Fred,” he sighed. He gave me the correct videotape and that night, Marya came over again and we took a second stab at it. This time it was the proper video, which quite thoroughly and dryly covered everything we’d need to know — not just how to get inside people’s houses, but every step of the demonstration, plus tips on closing the deal. As a person who is not comfortable with confrontation, I immediately dreaded the propsect of trying to talk someone into buying this thing if they didn’t already want it by the end of a live demo. A little red flag popped up in the back of my brain. It would not be the last.

Soon thereafter, Bill called a team meeting in the office’s cramped back room, at which the noob trainees — me and Marya and another guy from my high school class, Ronnie Webb — each had to perform a full demonstration in front of the managers and the handful of other salespeople, all of whom were in their 30s or older and had been at this for a while. When it came to my turn, I felt the weight of all the eyes in the room upon me and a wave of self-consciousness hit me hard. But I leaned into my demo and felt I did all right.

I would repeat it many, many, many times that summer. This is more or less how it went:

First there was the hook. In exchange for letting me demonstrate the Kirby in their homes, I offered potential customers a choice of premiums — either I would shampoo the carpet in any one room of the house, or I would give them a set of Quikut steak knives, which were manufactured by another firm in the Kirby corporate family. As shampooing carpet was a messy, laborious and time-consuming endeavor, I decided from the beginning to push the steak knives extra hard.

Once inside, I would ask the “consumer” to get out their current vacuum cleaner — guaranteed to be inferior to the gleaming die-cast aluminum Kirby, which I had been coached to portray as a floor-cleaning hybrid of Rolls-Royce and F-350 pickup, forged by Hephaestus himself in his great workshop on Mount Olympus, for the express purpose of relieving us mere mortals from the drudgery of housework. No matter what they had — humble Hoover, ritzy Rainbow, or anything in between — it was my goal to make it look weak and puny next to the Kirby, and that was actually pretty easy. This was years before “unboxing” videos became de rigueur entertainment, but I can tell you, people watched with rapt attention as I pulled out each shining piece of this brawny, magnificent machine and snapped it together. When fully assembled, the Heritage II model looked powerful, elegant and downright futuristic compared to most any other unit. And I honestly think it’s fair to say that it really was, on all counts.

As this was the ’80s, it was a sure bet that most any given home in South-Central Kansas had plenty of wall-to-wall carpet, so I would just choose a random spot in the middle of a walkway and start running their current vacuum over it. I’d keep this up for a long time, like maybe a minute or more just in a couple square feet, over and over — all the while talking about how much sand and grit and dirt gets down into the nap of the carpet, where it shreds the fibers apart and destroys the fabric long before its time. “That ought to be clean now, don’t you think?” (Consumer agrees.) Then I’d get out the Kirby, and instead of putting the big dirt-catching bag on it, I would cover the exhaust port with a simple, clean, black cloth, secured with a rubber band. This would allow us to capture and examine directly whatever was sucked up. (I recently discovered you can now get an official Kirby “Dirt Meter” for this task!)

And then came the first big selling moment. I would set the Kirby down in the center of the “clean” spot that I had just vigorously vacuumed. I would step on the power pedal, turning it on, then click the floor height adjusting pedal several times, until the nozzle was at the correct height for that carpet. I’d let it run for about 10 or 15 seconds, then switch it off and take off the black cloth. Every single time the thing was full of clearly-visible dirt. Like lots. Sometimes it would even shock me a little.

Then to really hammer that home, I’d ask when they had last vacuumed the mattress they slept on every night. A lot of folks, it turns out, never even think of doing that — and the ones that do are really serious about their hygiene. So I’d ask to see their bed, and have them turn back the covers to expose the bare mattress, and I’d put the Kirby on any spot. Switch it on, lower it to proper height, switch it off. This would inevitably produce a test cloth teeming with horrors — mounds of dead skin cells, mites, dust particles, powdery foam bits of mattress. On numerous occasions people audibly gasped, and this test alone would prove sufficient to sell me more than one vacuum that summer.

Then I’d run down all the attachments — the hose with its various brushes and crevice tool, the carry handle you could snap on in place of the tall upright push-handle to make it easier doing certain chores such as vacuuming stairsteps. All those came standard with the Kirby Heritage II. But then there were the premium add-ons, which we were strongly encouraged to push to our consumers. There was the floor shampooing attachment, of course. And then the Zipp Brush, a handheld wand with a turbine-powered spinning wheel of brushes inside the head, used at the end of the hose. It was actually a pretty effective tool for cleaning carpeted stairs, upholstery, etc. — especially in places where animal hair was an issue. Maybe the most amazing, though, was the Turbo Sander, another hose-end accessory that was not only a functional dust-free sander, but also a buffer and even a personal massager. Yes, this thing came with a big soft red massage pad, so you could enjoy a nice vibrating rubdown — just so long as you were able to relax with the jet-engine whine of the Kirby roaring full-tilt a mere four or five feet away from you.

If my consumer had chosen the carpet shampoo, this is the part of the demo when I would do it. Running the Kirby shampooer attachment was some nasty, messy shit, and fortunately I would only have to do it maybe a dozen times that summer.

And then, as the demonstration concluded, either Fred or Bill would swoop in to put the “hard close” on the sale — in person if they happened to be out in the field with us, or over the phone from the office. It should be noted that I was allowed to dicker on price, but any discount would come out of my commission, not from Kirby corporate or the local office. I was vigorously encouraged to offer financing, too, though that had to be arranged through Bill or Fred, either of whom would do the paperwork as necessary. (The fact that all this took place before the cell phone era meant lots of using people’s private landlines to make collect calls to the office, too.) In the end, if the consumer bit, I left the demonstrator unit with them to keep as their own, and went on my way with several hundred dollars to my credit. If they didn’t, I packed everything up and went on to the next house.

That next Saturday morning Marya and I met at the Kirby office, dressed presentably and armed with our best can-do attitudes. We were each issued a brand-new vacuum cleaner in the box, along with one each of all the bonus items we were to try to sell, plus a few replacement drive belts and dust bags, just in case. And then we were sent out to do our first demos in the wild, solo. Bill suggested an area in our own hometown, just around the corner from my house, actually, and Marya took one side of the street while I took the other. It only took a few knocks before each of us managed to get inside a stranger’s house.

Perhaps it is a testament to how bored people were before the internet, but I find it truly astonishing looking back now that so many would answer a random knock on their front door and invite into their homes a salesman, with the absolute promise that their next couple hours would be eaten up by a potentially high-pressure pitch for something very expensive, and which they probably didn’t really need at all. Our office did have a couple telemarketers who made cold calls to set up appointments, but out of the probably 100-125 demos I did that summer, maybe only ten were set up beforehand. The rest were all the result of cold knocking. Staggering.

A nice older lady let me in and it turned out she knew my grandma. She led me toward the back of her tidy midcentury ranch house to a little room only maybe eight or ten feet square, the floor of which was covered with shaggy mid-1970s carpet in a mix of rusts and beiges and sympathetic earthtones.

“We’re about to replace this rug,” she told me. “Do you think shampooing it now will make it less dirty a job when we pull it up?” My gut told me probably no, but I agreed to shampoo it if she would let me demonstrate the Kirby. It was not just my first demo, but my first time actually using the shampooer on a whole room of carpet in a real house, and I felt clumsy and conspicuously awkward through the whole process. I had to use her kitchen sink to get water and ask where she wanted to pour the filthy water at the end of the process, which turned out to be behind a bush out in front of her house. At the end I was sweaty, rumpled and wet — but the carpet was clearly much, much cleaner, which I could see surprised the lady of the house. “Wow, maybe we hadn’t ought to replace this after all,” she chortled, surveying my handiwork.

And just for that moment I thought, “I am about to sell this $1000 vacuum cleaner on my very first demo, and she’s gonna want that shampooer, too. Maybe even the Zipp Brush!”

As if on cue, the doorbell sounded and it was Fred at the door, coming in to check on my progress. The lady led him back to where I had been working, and he was visibly impressed with the job I’d done. As I carried my gear to the kitchen to clean it up, I heard him launch into his closing spiel. I was really happy he was there to do it, honestly, as I was still having trouble with the idea of putting any sort of pressure on. Not that it was necessary — I was just sure this lady was going to get her checkbook out.

I was wrong. She admitted that she was impressed with the Kirby overall — but said there was no way on Earth her husband would let her buy it, as he had already shelled out considerable bread some years before on their frankly rickety Filter Queen, and he hadn’t stopped complaining about that expense since. Dejected but upbeat, I made small talk with her while I broke down the Kirby and wiped the accessories and packed each item back in its box. Half-jokingly, I said that if she did replace that carpet, I’d like to have it to redo the interior of my old ’63 Rambler — and I was surprised when she immediately agreed. (Later that summer, she would call my grandmother’s house and I would go retrieve the roll of old carpet, and I did put it in my Rambler. And you know what? She said the removal process had been much less filthy than expected. So maybe my gut had been wrong on that one.)

Fred helped me carry my equipment out of the house and walked with me to my Mercury Monarch coupe, parked at the curb just a couple houses down the block. We loaded the stuff into my trunk. Fred slowly swung his head around to the left and right and leaned in conspiratorially.

“Listen,” he said in a low tone, “I wasn’t gonna say anything in the house there, but your girl’s had some trouble down the street and Bill’s probably already over there right now trying to straighten it out.” My heart jumped.

“What kind of trouble?” I asked. “Is she OK?”

“I don’t know, man,” Fred replied, sucking his teeth. “Sounded hairy on the phone. Anyway, why don’t you just cut your losses today and we’ll circle the wagons on Monday?”

That sounded fine to me. I went home and changed into sloppier clothes and waited to hear from Marya. Perhaps an hour later, she called — and she had quite a tale to tell.

Marya had been invited into the home of a woman she guessed to be in her late ’60s, and started doing a demo. Everything was going really well — the woman just loved the Kirby, obviously a major upgrade over her dilapidated discount store sweeper — until the moment her husband came in from mowing the back yard. He was clearly unhappy to see a salesperson in his house, and plopped down tersely on the edge of a chair in the living room with his arms crossed and a scowl on his face, staring at Marya as she nervously continued her demonstration. At some point around the introduction of the Zipp Brush, the husband abruptly stood up, marched to the front door, opened it, and pointed outside.

“We’ve seen enough,” he declared matter-of-factly. “Get out.”

Marya froze like a deer in headlights, unsure for a moment how to proceed. As the plainly mortified woman of the house meekly beseeched her husband to calm down, Marya figured it was best to just start packing up. She began breaking down the Kirby, and just as she went to put the first piece back in its box, the man was suddenly standing right over her, leaning down and barking directly into her face, his own visage red with rage. A pungent miasma of gin and tobacco smoke erupted from his mouth.

“I TOLD YOU TO GET OUT!”

Marya scuttled to pack faster. “I’m getting out as fast as I can, sir,” she said with strained politeness as she worked.

“NOW!” the man bellowed, kicking the box violently away from her across the floor. “I’M KEEPING THIS.”

Marya was not a timid person, nor was she afraid to tell someone to fuck off. She snorted, said, “Good luck with that,” and walked out the door as the poor woman of the house continued wailing a litany of useless pleas to her husband’s absent better nature. My girlfriend casually walked to the house next door and rang the doorbell there.

“Hi, my name is Marya,” she said to the woman who answered the door. “I’m really sorry to bother you, but I’m having kind of an emergency right now and need to use a phone for just a minute. You see, I was doing a Kirby vacuum demonstration for the nice lady next door and her husband threw me out and won’t give me back my equipment.”

The woman rolled her eyes and heaved a disgusted sigh. “Well, I’d like to say I’m surprised, but I’m not.” She opened the door and pointed to a telephone on a table across the living room.

Marya called Bill, who was manning the phones at the office while everybody was out in the field that day, and told him what had happened. He immediately hopped in his car and raced to the house where everything had gone south. Marya was waiting on the porch next door, where the kindly neighbor who had let her use the phone had poured her a nice glass of homemade lemonade. Other eyes peered from the porches and from behind windows of the adjacent houses. Bill knocked on the door, and the old man who had taken Marya’s Kirby came out on the porch and got right in his face, despite the fact that Bill had probably eight inches of height and 100+ pounds on him. Bill was very professional and polite the whole time, patiently explaining to the gent that the equipment he had impounded was valuable and he was going to have to give it back to the young woman.

And right then, the old man hauled off and punched Bill right in the middle of his face, hard.

Marya said she couldn’t believe it. Bill didn’t flinch, didn’t blink, not a hair moved out of place. He slowly and gently spread his hands up and apart in a calm display of non-hostility and said, “Friend, now if I don’t leave here with that machine, the Ark City Police will be right over to talk to you — and you I and both know you won’t like what they have to say.”

There was a long silence as the two men stared at one another on the porch. Finally, the old man blinked. He reached into his pocket and fetched out his car keys, said, “Don’t be here when I come back,” tromped past Bill to the pickup parked in his driveway and sped away. The man’s poor wife let Bill and Marya into the house and drowned both of them in an endless tsunami of apologies as they packed up Marya’s demo Kirby. As they were walking out the door, Bill turned to the woman one last time, tenderly took one of her hands in his, and looked her right in the eyes. With the greatest sincerity, he told her, “Ma’am, you have nothing whatsoever to apologize for here today. I am only sorry that so clearly kind and gentle a person as yourself has to put up with this sort of behavior.” Marya said the woman started crying, quietly pulled the screen door shut, then closed the heavy wooden door, leaving her and Bill alone on the porch with the Kirby.

“I guess we better get out of here before that gentleman comes back,” Bill said. He cut Marya loose for the day, and that was the end of our first Kirby demonstrations.

For the next couple months we were sent out separately, together and by the vanload into the wilds of South-Central Kansas, hitting one small town after another. The experience frequently bordered on — and sometimes careened headlong into — the surreal.

The first sale I remember making came while I was working solo in Oxford, Kansas, population ~1100. I had been assigned to an preset appointment out there, and the consumer had already specified they wanted a room of carpet shampooed. The place was a pretty modern house out in the country to the south of town, and the room in question was in fact massive, maybe close to 20 feet square, and covered in low-pile shag the color of concrete, with a grimy footpath wending its way across the center from one doorway to another. Additionally there was an irregular blue-tinted spot the size of a medium pizza off to one side, which I was told by the man who had scheduled the appointment was two-stroke oil.

This fellow’s home decor and personal attire and choice of vehicles led me to conclude that he was both a bachelor and some sort of cowboy, and through my whole demonstration he watched in brusque silence with arms crossed. His desire to get to the shampooing part was palpable; I could already feel he wasn’t a buyer, just a guy looking to get his carpet cleaned for free.

I worked my ass off on that big, dirty rug for at least an hour, and at the end, though it wasn’t spotless — a faint ghost of the big bluish spot could still be detected — all traces of the greasy walking trail had been erased entirely. As I prepared to make my final pitch, the cowboy stunned me.

“Well, how much is all of it, then?” he asked, for the first time showing the faintest sign of interest. I quoted the price for the base Kirby unit with its factory attachments, plus the shampooer, plus the Zipp Brush, plus the Turbo Sander…and though I can’t remember exactly what all that came to today, I’m pretty sure it totaled up somewhere between $1200 and $1400 — in 1987 dollars.

The cowboy didn’t blink. He didn’t even try to haggle. Ten minutes later I was out the door with his signed paperwork and a personal check for the full amount in my hand. I couldn’t believe it! That meant cash in my pocket, something like $300+ if I recall, real money in those days. A guy could easily buy a used car for that.

I drove into Oxford proper in high spirits, daydreaming about how much money I could make if I sold three Kirbys a week, or five… Maybe I am good at this? But maybe not. So far I had not shown myself to be good at all at reading people in this context — that first lady I thought was a sure thing but wasn’t, and then the cowboy’s complete poker face threw me off in the opposite direction. But I had proved to myself that I could do it, and for that moment, I was riding high.

At the tumbledown gas station in town I took a leak and got a soda pop and a microwave sandwich, which I ate in my car in the parking lot. And then I set out cold-knocking.

It was a weekday afternoon, and a lot of houses were empty, or at least nobody was coming to the door. Where there were people home, nobody was interested. I did manage to sell a couple of replacement drive belts and paper vacuum bags at houses where they already had Kirbys, but otherwise I just kept striking out, one street after another. I was getting hot and tired, dragging around my big Kirby box and steak knife set, and at one point I got back into my car to pee in a bottle, something I had never done before in my life and which filled me with a mixture of thrill and anxiety.

And then I rang the doorbell of a newly-built house on a block that was just being developed. Next to the door was a little homemade wooden sign in periwinkle blue which had the family’s name on it, accompanied by a nauseatingly cute pair of white geese with ribbons around their necks, painted in a forcedly folksy style. A smiling middle-aged woman came to the door and let me in. I was not prepared for what I saw inside.

No matter where one looked inside this house, the eye was greeted by geese in bonnets and bows, hearts and flowers and other country kitchen design elements, all done in shades of dusty rose and French blue. Though this motif was to become inescapable in the years that immediately followed, I had not yet witnessed it expressed at maximum volume, and it was overwhelming. I tried not to let on.

This lady was interested to see how the Kirby stacked up against her older Electrolux, but the fact that her house and a fair amount of the furniture was brand new made it hard to establish a baseline level of filth for comparison. I resorted to pitching her on preservation rather than cleaning; her brand new carpet would never get dirty in the first place if swept regularly with the powerful Kirby, which meant it would last much longer. Buying this $1000 vacuum cleaner wasn’t an expense — it was an investment in taking care of the new home into which she had poured so much of her heart (and money).

It didn’t work. I put her on the phone with Bill, who did his best to help put her over the top, but it was no dice. I thanked the lady for her time and attention, left her a set of knives, and packed my things back into the car. I drove back home tired but happy that I had at least made a sale — and a big one, with all the bonus add-ons, to boot! Not so bad for a day’s work.

Then came the morning when we met at the office to make a team run in the van. We were headed to Mulvane, a town which had not been canvassed in years, due to its having passed a Green River ordinance, which either requires traveling salespeople to procure a license from the city, or in many cases prohibits door-to-door sales altogether. One of the other salesmen — a bug-eyed, bowl-cut obvious freak named Paul, drove, and Bill and Fred rode in the back with me, Marya, Robbie and one or two others. Paul was a trip, a real goony bird to look at, but the most successful Kirby rep in the local office. He was smart and funny, with an easygoing and helpful manner, and I was surprised to find out he had a reputation for lingering in demos for hours, cranking up the pressure slowly like a Gestapo agent until the consumer finally broke. He also loved to drive the office van, a decade-old Dodge with a strong 318 V8 and performance-modified transmission — partly because it was fun, but mostly so he could dominate the tape deck with Emerson Lake & Palmer and Gentle Giant cassettes.

Upon arrival in Mulvane we pulled into the convenience store at the crossroads and took the opportunity to hit the bathroom, grab a drink, etc. There was a portable changeable-copy sign out front that read

SLU H PU PIES SOLD HERE

and as we were all piling back into the van, Fred pointed it out.

“Hey, y’all, this is your last chance to get one of them sloo hapoo pies.” I don’t know why I thought it was so funny, but I laughed too hard and too long.

And then we were on the streets of Mulvane. I got into a retired couple’s house almost instantly, and boy, were they happy to see me. They had a first-generation Kirby Classic, just about as old as I was, and they absolutely loved it — but its drive belt had broken and nobody had been around to sell them another one. I told them I’d give them a set of steak knives if they’d let me show them the brand new model and as soon as I opened the box, it was over. The gentleman of the house was especially enamored of the handsome, muscular Heritage II, and when I told him I could give him a trade-in allowance on his old Kirby, he stopped the demo right there. I ran outside and looked for the van, which I saw parked down the block. I waved furiously and saw the brake lights flash; whoever was behind the wheel had seen me. A minute later, Fred walked in, advised on us a fair trade-in price on the Classic, and the deal was done. We hauled their old unit out and threw it in the back of the van and I raced eagerly to the next house with a fresh set of steak knives in hand.

Rather shockingly, I managed to do another demo — and sell another Kirby — before lunch. I was giddy; I had never made as much money in a week busting my ass at Kentucky Fried Chicken or Long John Silver’s as I did that morning in Mulvane, a town that seemed to welcome us with open arms. Bill and Fred rounded up the crew and treated us all to lunch at Pizza Hut. Two other people had made sales, too, but I was singled out for praise and celebration for my double-dunk, and I am sure I was insufferably pleased with myself. I wolfed down my Personal Pan Pizza and was raring to get back out on the streets.

Bill dropped each of us off, one by one, a block apart, far enough that we wouldn’t overlap one another but close enough that he and Fred could keep eyes on us and rush in to help us close as necessary. I was working one side of a quiet residential street of postwar houses, with Marya across from me on the other side. We had scarcely covered a block when the company van careened around the corner at considerable speed, zipped down the street to where we were and stopped dead with a little screech of rubber. Bill leaned out the window with a perturbed look and made a big “come here” gesture with his free arm.

“Hey, kids, we gotta get in the van, right now!” he hollered.

“What the…?” I muttered under my breath. Well, he was the boss. I trotted straight to the van, threw my gear in the back, and climbed inside, followed closely by Marya. Everybody else on the crew was already inside except Paul, who was in someone’s house starting a demo. The van took off again and I heard Bill and Fred discussing which house Paul had gone into. They figured it out and Fred ran inside and jerked Paul out of there and within about two minutes we were outside Mulvane city limits.

As it turned out, someone had reported us to the sheriff’s office, and a deputy had come out to tell Bill to get the hell out of town or face a separate fine for every individual staffer in the field that day. And so we got the hell out, and headed west to try our luck in nearby Haysville.

That whole afternoon was a grind. It must have been late July or early August, and the humidity was cooking my legs inside my chinos like frankfurters. I dragged my equipment around for blocks, gave two fruitless demos, and by 7:00 or so that evening, my fat ass was exhausted. I went back to the van, which was parked at the end of a cul-de-sac in a new development, and flopped down on one of the vinyl bench seats in back. The windows were popped open for ventilation but there wasn’t much of a breeze, and sweat stung my eyes and rolled salty into my mouth.

Ronnie showed up next, and for a while it was just the two of us, as both Bill and Fred were out closing for the other reps. Ronnie was kind of a hick kid, not someone I’d been friendly with in school but not an adversary either. I always thought he looked like a little like a hayseed Tom Cruise, and though he came off a bit dickish, he really was sharper than he let on, and once in a while he’d say something really funny. Dusk encroached as we sat in the van chatting quietly about the day’s events, and the streetlight overhead came on. And just a moment later, illuminated in that gentle glow, we saw a mother skunk leading six little babies across the fresh asphalt, still radiating the day’s heat back into the night sky with the deepening of evening.

“I’m gonna get me one-a them babies,” Ronnie said, staring entranced out the van window at the adorable parade passing by.

“Dude, I don’t think that’s a good idea,” I replied, not sure how serious he was.

And then he swiftly and silently slunk out of the van, tiptoed up behind the line of skunks, snatched the last one, and hoofed straight back to toward where I sat, watching in stunned alarm. (The fact that he did all this in cowboy boots only added to my amazement.) Just before he reached the van, I hopped up out of my seat, shut the open bay door and depressed all the door lock posts. Ronnie stood outside, holding this cute but terrified little baby skunk up high for me to see.

“I got it!” he stage-whispered in excitement. “Come on, man, let me in!”

“No way, dude, you gotta put it back.”

Just then, behind him, the angry mama skunk emerged from the darkness at the edge of the streetlight’s glow and stomped determinedly toward Ronnie. I am sure I gasped; I know I pointed and shouted.

“Here she comes! Put it back! Put it back, dude! Get it away from the van!”

Ronnie froze for a moment in panic, and then sprang into heroic action. He slouched over low and trotted forward toward the hostile critter like a dogface crossing enemy lines in World War II, holding the baby out at arm’s length in front of him the whole way. When he was close enough to the mama that she squealed at him, he leaned down and gently placed the purloined kit on the ground in front of her, then turned and ran full-speed back to the van, where this time I let him in. The mama skunk squealed and huffed some more, sniffed her baby over, and then the two of them walked off into the dark.

It would have been a dramatic end to a long day, were it the end. Instead it sprawled on for almost two more hours as the whole beat crew waited in the van for Paul to finish one of his epic-length demos — that did not even yield a sale in the end. And then there was another hour of driving to get home. I wished I had quit after the pizza.

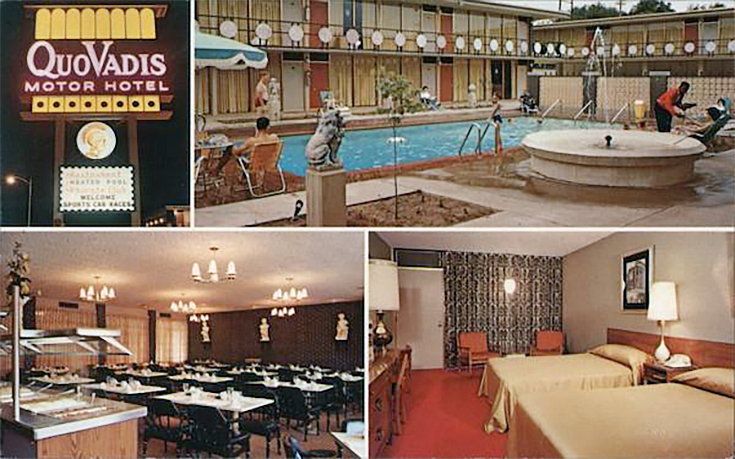

Then came the Kirby regional powwow. Our whole team met extra early in the morning, climbed in the van and headed south over the border into Oklahoma, where we met other area crews at Ponca City’s swanky Quo Vadis Motel, which had a big conference room that could be rented for such events. The first part of the day was reserved for official business, with a scheduled agenda that included some of the Kirby higher-ups handing out awards to reps who had met their goals, and discussing objectives for the next period going forward. I was mostly looking forward to the free breakfast buffet, which turned out to be not half-bad. I piled so much food on my plate, Marya frowned at me, leaned in close and murmured into my ear, “You’re gonna get the shits from all that bacon.”

I could only smile in return. “Worth it,” I whispered, cramming another greasy slice into my mouth.

I was surprised when the highest ranking Kirby man called me up to the front of the room, and doubly so when he awarded me a bronze key fob in recognition of my first three sales. I was, in fact, the only person from our office to win an award that day — with the exception of Paul, who was one of the top three salesmen in the whole region. I am not 100% sure looking back now, but I think he got a brass belt buckle for that.

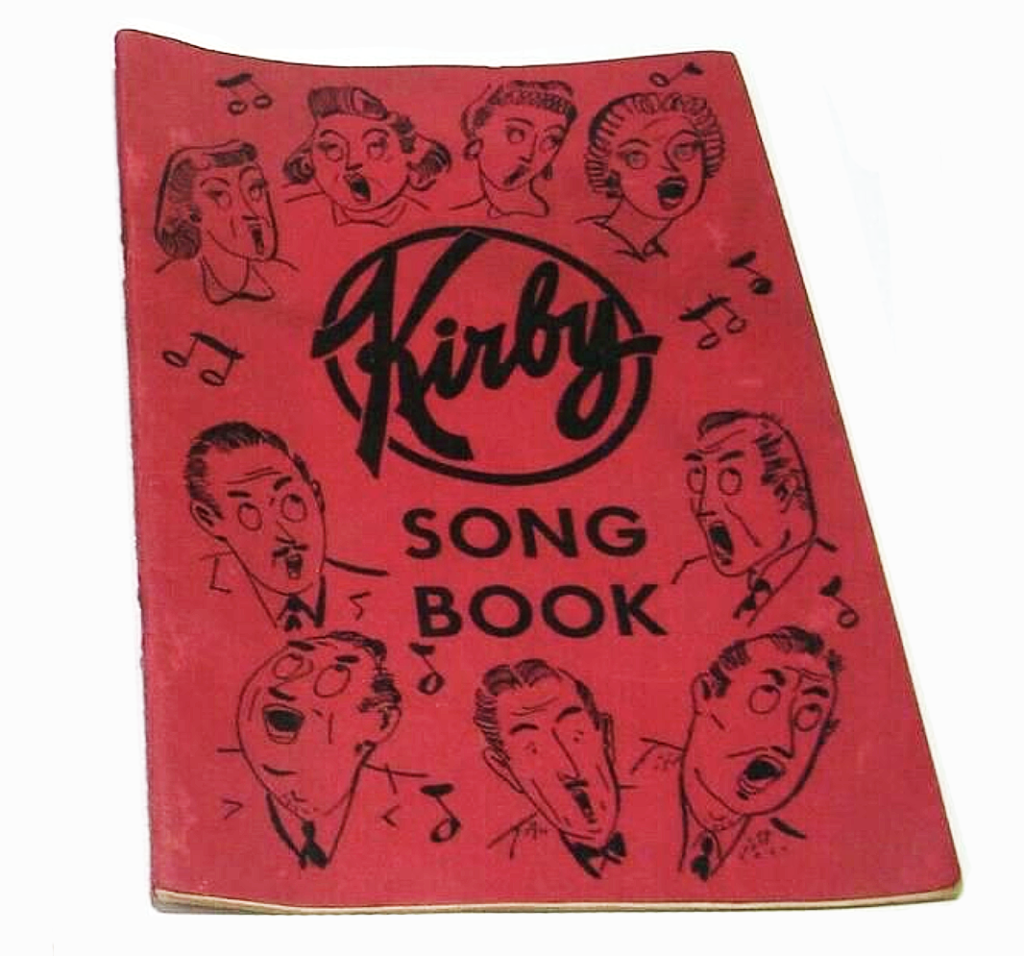

At the center of every sales organization beats the heart of a cult — I had seen my grandparents narrowly escape being sucked into the Amway vortex just a few years prior — and Kirby was no different. Some of these regional director guys were True Believers and their fervent testimonials were straight out of my old church days — just replace “Jesus” with “Kirby.” The meeting veered from business conference to tent revival to pep rally and back again, complete with spirited singalongs of “hymns” from the Kirby Songbook. By about lunchtime, the meeting was over — but our office field trip was not.

Our crew piled back into the van and headed to a local park, where Bill had reserved a covered gazebo with picnic tables. He and Steve grilled hot dogs and hamburgers and handed out paper plates and there were tubs of baked beans and potato salad and bags of potato chips and cans of generic soda pop. We played silly party games for various Kirby-branded prizes; I don’t remember where they came from but somehow there were a half-dozen box turtles there and we painted their shells in dayglo tempera paint (which washes off quickly in water) and raced them for bonus prizes. Watching the turtles try to escape, only to be repeatedly picked up and put back where they started, sent me into a melancholy fugue. Was this how we did our “consumers” as they tried to politely wriggle loose from our endless spiels? Or was it me who was the turtle, with my own aspirations and ideas and directions in mind, but always pulled back to the same old dynamics of family and school and work and social expectations?

The picnic was over for me.

The fall semester at community college loomed closer and I knew I would have to give up the Kirby gig. Though I did earn some money that summer — I think I made somewhere north of a dozen sales — I sure wouldn’t miss the sweaty, dirty drudgery of dragging 30 pounds of gear around under the unforgiving Kansas sun, or the awkwardness of being in other people’s personal space and making them increasingly uncomfortable in order to sell them something, or the hours trapped in the van until well after dark.

And then two things happened more or less at once that really put the nail in the coffin on my career as a door-to-door peddler.

Let me flash back to earlier in the summer, when I made a sale to a poor working-class couple who lived in an entropic mobile home on the edge of tiny Geuda Springs. This was another appointment that had been set over the phone, which felt like a good sign — these people had already been cold-called and taken the time to schedule an appointment, so it showed they were interested going in. I arrived at the address and had second thoughts. A frayed American flag flew from the corner of the rough, home-built awning over the front steps, and inside I immediately caught sight of a well-stocked gun cabinet, a large and garish wall tapestry emblazoned with a heroic image of John Wayne, a calendar featuring a photo of President Reagan on horseback, and a large and ancient family Bible, perched conspicuously on top of a small television. I would guess the husband was in his early 30s, bearded and paunchy but unfailingly country-polite, and his handshake was note-perfect for a good ol’ boy. The wife was maybe a decade younger, probably closer to my age than his, and the few times she spoke at all, she was very sweet, but demurred at all times to her husband.

As one might expect given the decor, these folks were quite conservative in their political and social ideology, and it was made clear during my demo that the man was the proud breadwinner in the family, and the woman stayed home to take care of what little house they had. Looking around, it was obvious that their economic status was grim at best, and halfway through the demonstration I was honestly ready to bail. But by that point, to my surprise, the husband had sold himself on the tough, versatile, useful — and importantly, American-made — Kirby Heritage II. It was a powerful tool that his wife could employ in her position as homemaker, and he had a lot of fixer-upper jobs on his to-do list, too, for which the Turbo Sander would be super helpful.

“So tell me, sir, if you would,” he said, looking me square in the eye, “what is the rock-bottom price on this?”

I called the office and talked under my breath with Bill about how low I could go and still get paid at all on the sale, and we discussed the financing these folks would have to secure, too. Just because this guy wanted it so bad, and was in such dire financial shape, I ceded most of my commission just to make the sale. Bill ran their numbers and blew a loud sigh through his teeth.

“Damn, these folks are strapped to the wall out there,” he muttered. But he shot me a price cut that I was OK with, and he said he could make the financing work on paper, and there were hearty smiles all around.

A nauseous stew of conflicting thoughts and feelings churned in my gut. On one hand these poor, decent, salt-of-the-earth people were so fucking happy to have this revolutionary appliance in their life. It was literally the nicest and most expensive thing on their property, and as I walked out to my car to drive away, I heard the Kirby roar back to life inside the trailer house. I imagined them running it over every surface in delight, and that made me feel good. But then there I was saddling them with more debt that they obviously didn’t need, especially at a time when there was so little opportunity in the area for them to bring more income into their household. They could have survived just fine with a $40 Hoover from K-Mart. But now they had something they were really proud of, a shining symbol of prosperity that they could pray would be just the first of many. I let myself off the hook right there so that it wouldn’t keep eating at me.

Weeks later, around the beginning of September, I walked into the office and Bill took me aside, a downcast look on his face.

“Remember them folks out at Geuda, in the mobile home?” he asked. I nodded. “Well, we are gonna have to go repo their machine. Our finance people sent back their app rejected.”

“What!?” I blurted. “They can do that? I thought it was approved when I talked to you on the phone.”

It was not. My heart sank. I thought of how happy that couple had been, the joy beaming from their faces as I had walked out their door that night. And then a thought struck me like lightning — was Bill was going to make me go take their Kirby back from them?

“No, no,” he assured me, “I’ll handle it. Don’t worry.”

A dark cloud followed me around all that week. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. Was this right, the job I had been doing out there in the field all summer? Was it even OK? I thought of the cowboy, and the old couple in Mulvane, the DeMarcos who lived up the street from my house and whose kids were in my class, the independent trucker guy in Derby, my grandma’s well-off widow friend Celeste — each of them, and several others, had all quite happily bought a Kirby from me, and it was something they considered an asset to their households.

But then I’d think back to that trailer house, and a couple other very humble homes I’d made sales in that summer, and I couldn’t help but feel like I had somehow been taking advantage of people’s misguided ideas about the American Dream, preying on some of our most vulnerable citizens. I did not care for it at all.

I did a handful of demos after that, but what small amount of heart I had ever put into it was no longer there. The final cut came in tiny Conway Springs, where I was knocking doors solo on a weekday afternoon, having completed an appointment out there without making a sale. A couple in their 70s let me into their cozy postwar home, which I was rather shocked to find tastefully decorated in extremely well-kept, stylish furniture from the 1950s. I nearly swallowed my tongue when I saw they had a for-real Herman Miller Eames chair, a piece of midcentury furniture so iconic even a rube like me recognized it immediately.

The couple could not have been nicer, and almost immediately I warmed up to them and they to me as though we already knew one another. They both watched earnestly, asked good questions and made pertinent observations, and as the demonstration went on I thought we had a deal going for sure. They even had an older high-mileage Kirby for trade-in. Slam-dunk.

And then I made a grave error.

I don’t even remember exactly how I said it, but I mentioned something about “when the grandkids come over to visit…” and that was it. The smile disappeared from the sweet, prim woman’s face, which melted in slow motion into a mask of grief. Huge hot tears manifested in the corners of her eyes and rolled down her face as I froze, unsure of what I had said. A quiet moan emanated from her, escalated into a sob, and she put her hands over her eyes. “I’m sorry,” she said in a quiet quaver as she stood and walked quickly out of the room, a sorrowful bay following behind her down the hallway into another, unseen part of the house.

The older gentleman sighed and fixed on me a gaze of kind pity.

“Look around you, son,” he said quietly. I did. I saw an elegant room of furniture, some tasteful wall art, a framed Olan Mills portrait of the couple taken probably in the 1960s… I wasn’t sure what I was supposed to be looking for. “Do you see any pictures of children?” I admitted I did not.

A light went on in my head. I had been stupid as a mule.

“My wife is barren. We were never able to conceive a child.”

“Sir, I am so sorry,” I said, feeling impossibly small and disgusted with myself. How could I have not noticed? There was no sign whatsoever that there had ever been a child in that house in 35 years, and even after a whole summer spent inside random strangers’ homes, trying to get a feel for who they were by the clues in their surroundings, I had not picked up on that.

“You ought to pack your things and go.”

I drove all the way back to Ark City with the radio off, putting mile after mile behind me in total silence, unable to stop thinking about that poor lovely woman, most likely curled up in a fetal position in a dark bedroom of her house, triggered into reliving her life’s central agony by my accidental appearance on her doorstep. And she had been really in a good mood during my demo, too; I felt like I had lifted her spirits up, only to fling them down hard onto the jagged rocks of heartbreak.

I checked my demo equipment back into the shop and told Bill I was out. He said he understood and shook my hand and wished me well. Marya had already quit by then herself, leaving behind a pretty slim crew. As I looked back on the sad, dumpy Kirby local office one last time, I saw two fresh-faced new recruits watching the same training video I had seen just a few weeks before, and it seemed strange that so much had happened in so little time. My whole career as a Kirby rep had stretched only from June to September — but it had felt like a long, long year.

And there I stood, a free man — a legal adult, out of high school, about to attend college, just like people did in the movies. True, I was still living with my grandma, still in my same little town, still in my first (extremely unhealthy) romantic partnership — but for the first time in my life, really, it seemed like there might be a future worth imagining. And, unlike the mighty Heritage II, that didn’t suck.

Oh, AND I loved this piece! So interesting to read the experiences of a fellow Midwesterner from the same era and see my my experiences reflect med back at me!

Thanks for your comments! It was certainly an informative experience for me.

Michael, my one-day Kirby experience was a crystallization of the Geuda story. I went around with an middle-aged man, he in a cheap suit but pleasant enough, though clearly a salesman. We never even did a demo, but we got into a few houses. All I remember are sad-eyed women at home alone, with clearly no prospects beyond that, at least that they could recognize in their current head-space. They’d talk a while but they all felt so sad and desperate in their blue-collar neighborhoods full of split-level ranches. So, I couldn’t do it—and it seemed like it had all happened too fast, from showing up at the office in the morning, going out on the road, and coming home with a Kirby to practice with, which went straight back the next day. Luckily my grandparents gave me $1,000 for graduation that I stretched out until I went to school in the fall.