As a child growing up in the 1970s I assumed it was a given that pretty much all grown-ups smoked cigarettes. Clouds of acrid smoke drifted wherever adults congregated; even in grocery stores and the lobbies of doctor’s offices one could find large public ashtrays brimming with discarded butts. And nothing was worse than being bottled up in the car with smokers with the windows up and the air conditioner recirculating the stale, stank air. My younger self could not possibly imagine ever voluntarily smoking a cigarette.

And then in 1988, at the age of 19, I moved away to a college dormitory where a shocking number of my fellow teens were already hearty smokers. After probably six weeks of being offered smokes I gave in and had my first cigarette — a Marlboro Menthol. I was shocked at the buzz it gave me; people had warned me my whole life about drugs like pot and LSD but nobody told me regular old nicotine packed such a wallop! The next day at a convenience store I found myself eyeballing the cigarette selection for the first time. Showing brand loyalty right off the bat, I bought a pack of Marlboro Menthols — and set off on a two-decade journey through the yellow-stained abyss of chain smoking.

I didn’t stick to menthols for long, but looking back I have to wonder if I would have picked up the habit at all, had someone not offered me a cigarette that sounded like it might taste good. Maybe that’s wishful thinking; it’s of course impossible to know now. But I have to admit the promise of a minty flavor explosion certainly made it easier to take that first step. After all, nobody wants to lick an ashtray — but who doesn’t love a Starlight Mint? Or the sensation of biting into a York Peppermint Pattie? If the plan was to get me on nicotine, it worked.

Fast-forward to this week, when the Biden Administration announced its desire to ban menthol cigarettes in the United States, with the intention to “help significantly reduce youth initiation, increase the chances of smoking cessation among current smokers, and address health disparities experienced by communities of color, low-income populations, and LGBTQ+ individuals, all of whom are far more likely to use these tobacco products.” The proposal is not new, and in fact has been kicked around Washington DC for years, provoking much harsh reaction from a wide coterie of groups, including the Council on Racial Equality (CORE), the National Black Chamber of Commerce, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and numerous police organizations — all of whom see this move as potentially creating more harm than good within African-American communities.

But let’s hold on a second. Just how is it that menthol cigarettes in specific have become so closely identified with American Blackness in the first place? The history behind the connection is a remarkable — though perhaps not surprising — story of postwar industrial America, in which a vulnerable segment of our society was deliberately and cunningly cultivated as consumers of a lethal and highly addictive product by a bunch of real-life Mad Men.

A Happy Accident

The menthol cigarette was invented in the 1920s, when a man named Lloyd “Spud” Hughes stashed some tobacco in a tin where he kept menthol crystals — considered at the time something of a medicinal miracle, commonly used to treat colds and other minor ailments. The next day he lit up a cigarette and was pleased to discover that the tobacco had been imbued with the cooling vapors of the menthol. He patented the process, sold it to an investor and Spud cigarettes hit the market in 1927. Though several imitators popped up, none comprised a real threat to Spud’s supremacy until the launch of the Kool brand in 1933.

Kool’s sophisticated advertising — including a series of animated shorts featuring their famous penguin mascots — quickly built the brand into a powerhouse. But the company’s most successful and long-lasting marketing strategy played up the supposedly therapeutic, “healthier” aspects of smoking menthols, suggesting that they were somehow less irritating than standard cigarettes. (Fun fact: Smoking menthol cigarettes does tend to feel smoother — because the substance has a numbing effect on the throat and lungs, inhibiting the body’s ability to signal irritation to the brain.) Smokers were urged to switch to Kools to give their throats a break from the harshness of regular cigarettes, or to treat themselves when suffering a case of the sniffles. In no time, Kool was the top menthol brand, and would remain so for the next 20 years.

The introduction of Salem cigarettes in 1956 was a game-changer for the menthol market segment. Unlike all previous menthol brands, which impregnated the aromatic compound directly into the tobacco, Salem instead provided its burst of minty freshness to unflavored tobacco by way of a mentholated filter. This milder cigarette became an instant hit with both men and women and helped drive the overall market share for menthols from 5% in 1955 to 16% by 1963.

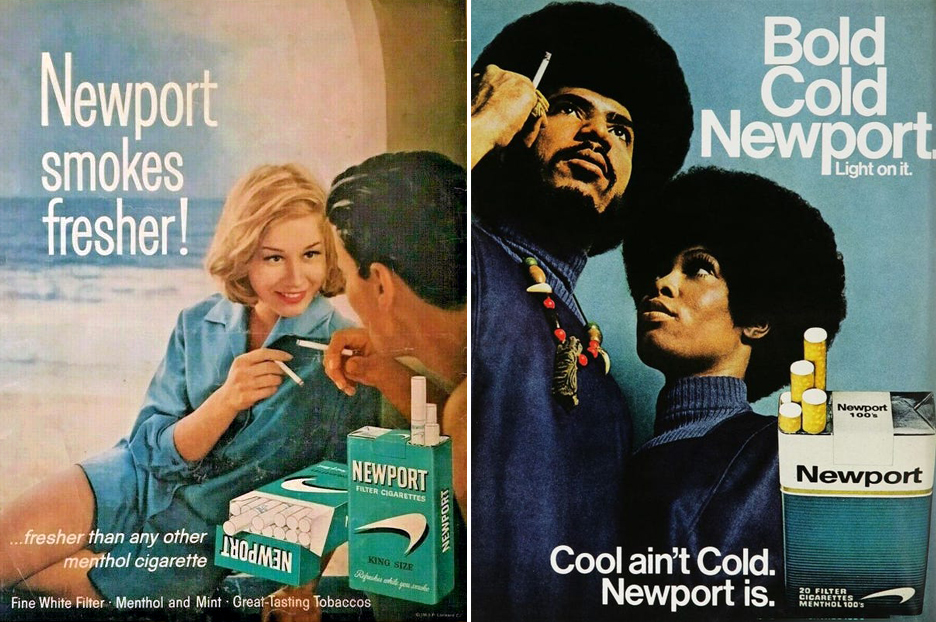

In this time period cigarettes were advertised vigorously in print and on radio and television, imprinting a ubiquitous image on our society of smoking as not only normal and natural but almost aspirational. Looking back, in ad after ad after ad we see successful white people relaxing with a leisurely lungful of rich tobacco as they stroll through nature or enjoy a spot of boating or do a wide variety of other successful white people stuff. At first there was little effort spent marketing cigarettes — menthol or otherwise — specifically to the Black community.

The Black Market

A number of factors came into play which would change this. First there was a tobacco industry survey taken in the early 1950s, which included only one menthol brand — Kool — in its poll of customer preferences. While a paltry two percent of white smokers named Kool as their preferred cigarette, five percent of African-American smokers indicated the same. This planted a seed in the collective hive mind in the marketing department at the Brown-Williamson Tobacco Company. Playing off the longstanding tradition of using baseball players to endorse cigarette brands, they created an ad campaign featuring Elston Howard, the utility player who broke the New York Yankees color barrier in 1955. Placed in Black-aimed publications such as Ebony, this ad and many that came to follow would begin to redefine how menthol cigarettes were advertised in the United States.

The Great Migration of rural Blacks to urban areas had also fueled many new cottage industries in specialty products and publications tailored to their specific cultural tastes and needs. This in turn led to new levels of sophistication in the niche marketing aimed at selling to African-American consumers — a group whose relative inexperience with being courted by business left them uniquely susceptible to the power of targeted advertising. By the middle of the 1960s, Ebony‘s tobacco ad load had tripled, more than double that of Life magazine — and the majority of those ad placements were for menthol brands. By the end of the decade, marketing menthols to the general (aka white) population was done practically as an afterthought, as so much effort was focused on not just securing the Black consumer base, but expanding it — by any means necessary.

Lorillard Tobacco launched their menthol Newport brand in 1957, but despite a series of popular television ads, they couldn’t get a foothold in a field dominated by Salem and Kool. In the 1960s the company launched a pilot program to recruit new smokers, sending attractively-dressed young women in company vans to schoolyards and parks near Boston-area housing projects, where they handed out free Newports to anyone who wanted them — including children. (This was not widely reported until 2010, when Lorillard was finally held responsible in court by the estate of a lung cancer victim whose lifetime of smoking started at age nine with a Newport giveaway.)

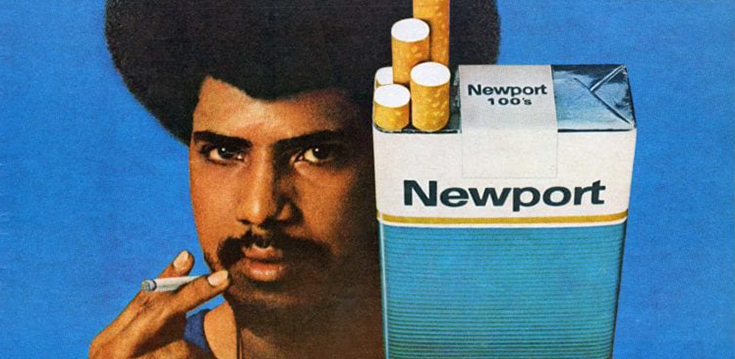

Newport also spent much of the ’60s in an advertising arms race with Kool, with the goal of generating the greatest possible hip factor among young African-Americans. The old Rhode Island imagery of comfy sweaters and crisp sails in the blue sky was marginalized entirely by James Brown references — “Newport is a whole new bag of menthol smoking” — and tough-looking, ice cold Afro chic.

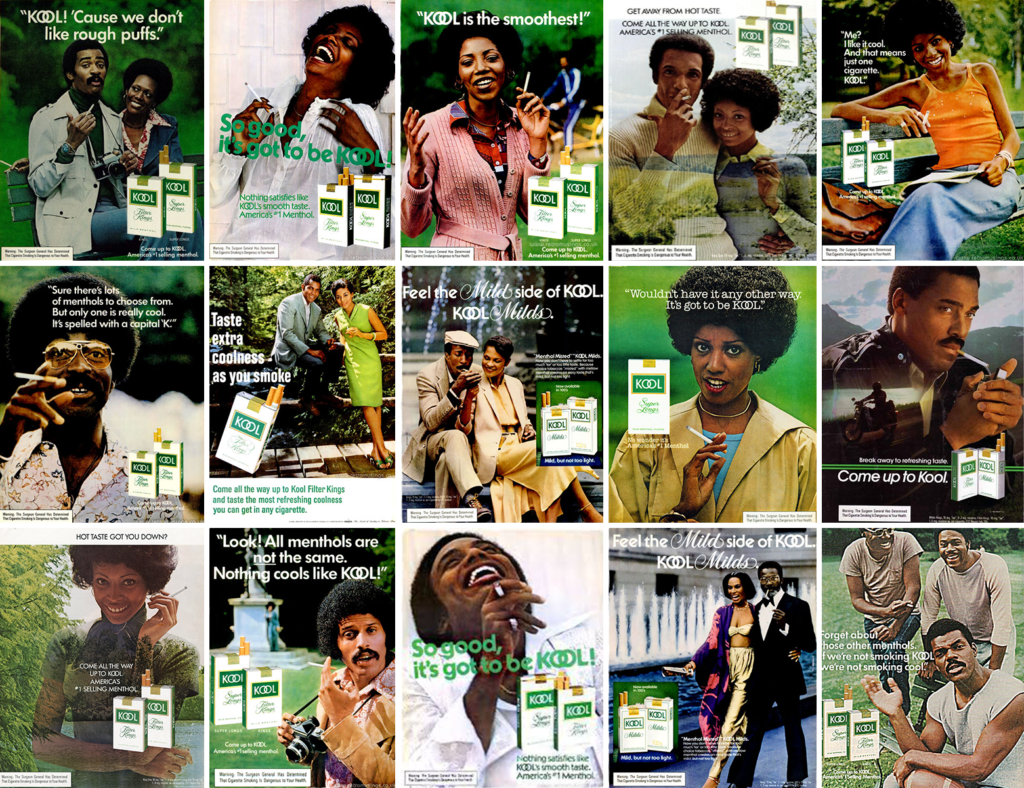

But Kool manufacturer Brown-Williamson wasn’t about to be outdone by Lorillard or anyone else. What started with one baseball player’s endorsement snowballed into a veritable avalanche of targeted Blaxploitation print advertising, the likes of which the world had never seen. Black Kool smokers were now uniformly depicted in exactly the same way white menthol smokers had been a decade before — well-dressed, relaxed and enjoying quality leisure time in nature with a refreshing cigarette.

It worked. Kool not only drew existing smokers over from other brands, but became the smoke of choice for countless noobs taking up the habit in the 1960s and ’70s as well. By 1978 the combined marketing efforts of Kool and Newport had grown the US market share for menthols all the way up to 28%, with some 70% of Black smokers preferring menthols over regular cigarettes — a shocking disparity against the 30% of white menthol users.

As it turned out, however, the mighty Kool was about to take a tumble. Some of the blame may be laid to rumors that Kool’s filters were made with fiberglass, intended to harm the lungs of the African-American smokers to whom the brand was marketed — or that the “K” in “Kool” stood for “Ku Klux Klan,” and that somehow that nefarious organization had cooked up the brand in order to addict and kill Black Americans. But just as likely, the famously strong-flavored Kool fell victim to the era’s growing preference for cigarettes with lower levels of tar and nicotine. Brown & Williamson quickly launched its own light menthol brand — Kool Milds — but found itself eclipsed in sales again by Salem by 1981.

Backhanded Philanthropy

Targeted advertising clearly worked very hard (and very well) to create a deep association between Black American smokers and menthols — but that was not the tobacco industry’s only mode of outreach into the Black community. Going all the way back to the 1950s, with the beginnings of the Civil Rights era, tobacco companies — eager to develop a strategic relationship with African-American consumers in their native Dixie and beyond — embarked on a cynical program of targeted philanthrophy for Black causes. This support, especially in the early days when very few national corporate entities dared to show love for the African-American struggle, endeared them to many and continues to this day to help shield them from any potential anti-tobacco activism that might crop up within the Black community.

Likewise, the sponsorship of major music events dedicated to predominantly Black music forms is another strategy that has helped cement menthol brands into the psyches of Black smokers. There is the Kool Jazz Festival, the Philip Morris Superband, The Parliament World Beat concerts, blues and jazz showcases sponsored by Benson & Hedges, on and on. (Just coincidentally the Newport Jazz Festival, named for the town and not the cigarette, was in fact established by a member of the Lorillard family.) Tobacco companies, pushing their menthol brands, routinely very publicly position themselves as supporters of African-American culture, associating themselves with vital artists and musicians — all in a calculated and sustained effort to hook more young Black people on nicotine — and keep them buying their brands.

The Newport Explosion

In the mid-1980s, tired of always being number three, Lorillard engaged in an unprecedented long-haul campaign of “urban market” advertising. A Stanford University study on the subject later reported that as a result of this strategy, “school neighborhoods were increasingly likely to have lower prices and more advertising for Newport cigarettes as the proportion of African-American students rose. The same was true of neighborhoods with higher proportions of children aged 10 to 17.” The number of teenagers smoking Newports doubled between 1989 and ’96, and more Latinx and white kids were drawn in as well — a side effect of Lorillard’s school-zone marketing, which in addition to print and point-of-sale advertising included popular discount coupons, typically requiring the purchase of multiple packs of cigarettes.

Even in the wake of the 1998 signing of the so-called Master Settlement Agreement between Big Tobacco and state governments around the country — designed to address generations of disease, addiction and death sowed by the industry — the hustle continued. Between that year and 2005, tobacco companies made massive cutbacks in their advertising — except where it came to their menthol brands, on which they spent more. Since the 2000s, fully half of all advertising for US cigarette brands has been for menthols.

In addition to their highly effective advertising strategy, Lorillard — as has long been common in the industry — also labored behind the scenes to make their product tastier and more addictive. They habitually tinkered with both the nicotine and menthol content of Newports; in 1998, though the brand was already tied with unfiltered Camels as nicotine champs of the US market, Lorillard’s labcoats added an extra ten percent. This was done deliberately in an attempt to create more young addicts.

In 2014 R.J. Reynolds swallowed up Lorillard, taking over the production and marketing of the Newport brand. Unfortunately the new company has continued to target Blacks and young people with a mixture of traditional advertising and new approaches such as the Newport Pleasure Lounge, a climate-controlled “party truck” set up at music festivals and youth culture events. In this setting the company skirts modern laws against giving away free cigarettes — by selling them for one dollar a pack, roughly six to seven times less than retail cost.

By 2005, eight out of every ten cigarettes sold to an African-American was a menthol — and one in every two was a Newport. This remains roughly the same today. And Newport isn’t just the number one menthol brand by a landslide, it’s also the number two brand in America, of any kind — second only to Marlboro. Menthols are so important to the tobacco industry that in 2009, when Congress granted regulatory authority over tobacco to the Food & Drug Administration, all flavored cigarettes were outlawed — except menthol. The tobacco lobby was willing to bend a long way, but that was just a bridge too far.

A Turning Point?

And now, after civil rights leaders and representatives of Black-oriented health organizations have spent decades calling for the ban of menthol cigarettes, it appears Joe Biden is prepared to grant their wish. But for every argument for the ban, it seems there is a counterargument, as other interests voice warnings that banning menthols will lead to greater police abuse of minorities. (Which to me seems like a startlingly frank assessment of an entirely different problem, and doubly so considering that assessment is shared by the ACLU, Black police organizations and contemporary right-wing pundits.)

Proponents of the ban stand ready to risk the negative repercussions on the basis that longstanding inaction on the part of government — which has contributed to an ongoing health crisis among African-American and other at-risk groups — is no longer acceptable. An FDA report suggests that banning menthols “would lead an additional 923,000 smokers to quit, including 230,000 African Americans in the first 13 to 17 months after a ban goes into effect.”

It’s a worthy goal, and should President Biden get his wish and see this ban enacted, it will — despite any potential blowback from law enforcement overreach — almost certainly curtail the current level of smoking in America to some degree. Regardless of the fallout, one thing is sure — banning menthols will at least put an end to a truly sordid chapter in the history of American commerce.