I grew up in the ’70s on the Cherokee Strip, right on the Kansas side of the Oklahoma border, and our hometown had a pork processing plant that employed many of the locals (including, coincidentally, my then-estranged father). The packinghouse, as the locals referred to it, was frequently swarmed with big diesel trucks, some equipped with refrigerated trailers for hauling away finished packages of bacon, hot dogs, hams, etc., and others pulling livestock haulers filled with doomed hogs, headed to the last stop on their way to becoming bacon, hot dogs, hams, etc.

My hillbilly stepfather David drove the latter for a living. He worked for a local owner-operator who had I think three semi-trucks, one of which was a white White hitched to a long livestock trailer painted red with a wide horizontal white stripe all the way down both sides. This one was assigned to David. I spent countless hours goofing around on the bare dirt lot where his boss kept his rigs and maintained a tiny business office. The property was maybe two or three acres in size, located on the southwest edge of town, and outside the big Quonset hut where most of the action happened, there not much more to explore other than an enormous brushpile and a foul-smelling lagoon where they hosed massive quantities of hog shit out of their trailers after each highway run.

“Be careful around the lagoon,” David told me one hot afternoon in the summer of 1977. “If you fall in, you’ll come out looking like a mummy.” After that I gave the fetid pool a wide berth.

Sometimes I got to accompany David on a run, if it wasn’t too far away. I went as far as the Oklahoma City Stockyards, anyway, and had the great fortune to experience the true red-blooded, blue-collared, salt-of-the-earth life of a trucker — exactly at the moment America decided truckers were just the absolute coolest.

Those of you too young to remember this may have difficulty processing the notion that through much of the middle of the 1970s, this country celebrated truck drivers as quintessential folk heroes of the time. This adulation was nothing new, of course, to longtime country music fans, who had by then been making hits out of truck-driving songs for many years. But in a decade known for over-the-top fashion and glitz and decadence, seeing the humble denim-clad trucker elevated in the mainstream mass culture to iconic status as modern-day cowboy came right out of left field.

One of the unlikely influences on this phenomenon was an advertising agency in Omaha, Nebraska, whose creative director was a fellow named William “Bill” Fries, Jr. Born in 1928, Fries grew up in rural Iowa surrounded by music; his parents and uncles had a popular regional band in the Depression era, and as a youngster he sometimes sang with them in public. He loved classical music, and played clarinet in school bands in high school and his brief time in college. He was also long interested in the visual arts, inspired by the early animated films of Walt Disney, which as a child he watched repeatedly in his local theater. By the time he enrolled at Iowa University, he was an accomplished illustrator.

In 1950, at age 21, he moved to the nearest big city, Omaha, and got a gig working as commercial artist for a television station. This turned out to be a great fit for the young man, and he spent ten years at KMTV, learning many arts-related skills on the job. During this time he also enjoyed doing set design for the local opera and ballet companies, which allowed him to work close to music, his heart’s truest love.

Across town at the Bozell & Jacobs ad agency, execs were impressed with Fries’ work and in 1960 they offered him a position at twice his current rate of pay. He jumped at the chance. Fries fit right in at B&J and it didn’t take long for the team there to realize what a coup they had pulled off in hiring him.

In 1970, the same year Fries was promoted to creative director, the Union Pacific railroad was shopping around for a new ad campaign. Fries surprised his team — who were largely unaware of his musical past — by writing a song he hoped might help win the lucrative contract.

Union Pacific president John Kenefick absolutely lost his mind over the song, insisting Fries play it several times in a row and immediately giving Bozell & Jacobs the coveted deal. “Great Big Rollin’ Railroad” was used across all UP’s marketing for years thereafter, and even played a central role in the railroad giant’s pavilion at the Spokane World’s Fair in 1974.

But Bill Fries was just getting warmed up. In his decade at B&J he had developed a pitch format called the “Five Screen Slide Show,” which he used to great success in presenting ideas to potential clients — and the biggest idea of all was that a good television ad campaign could benefit even the smallest company. One business that took the bait was the Metz Bakery of Sioux City, Iowa, a regional producer of bread and other baked goods. The owner, Bill Metz, was hoping to establish a strong brand identity for one of his company’s flagship products, Old Home Bread.

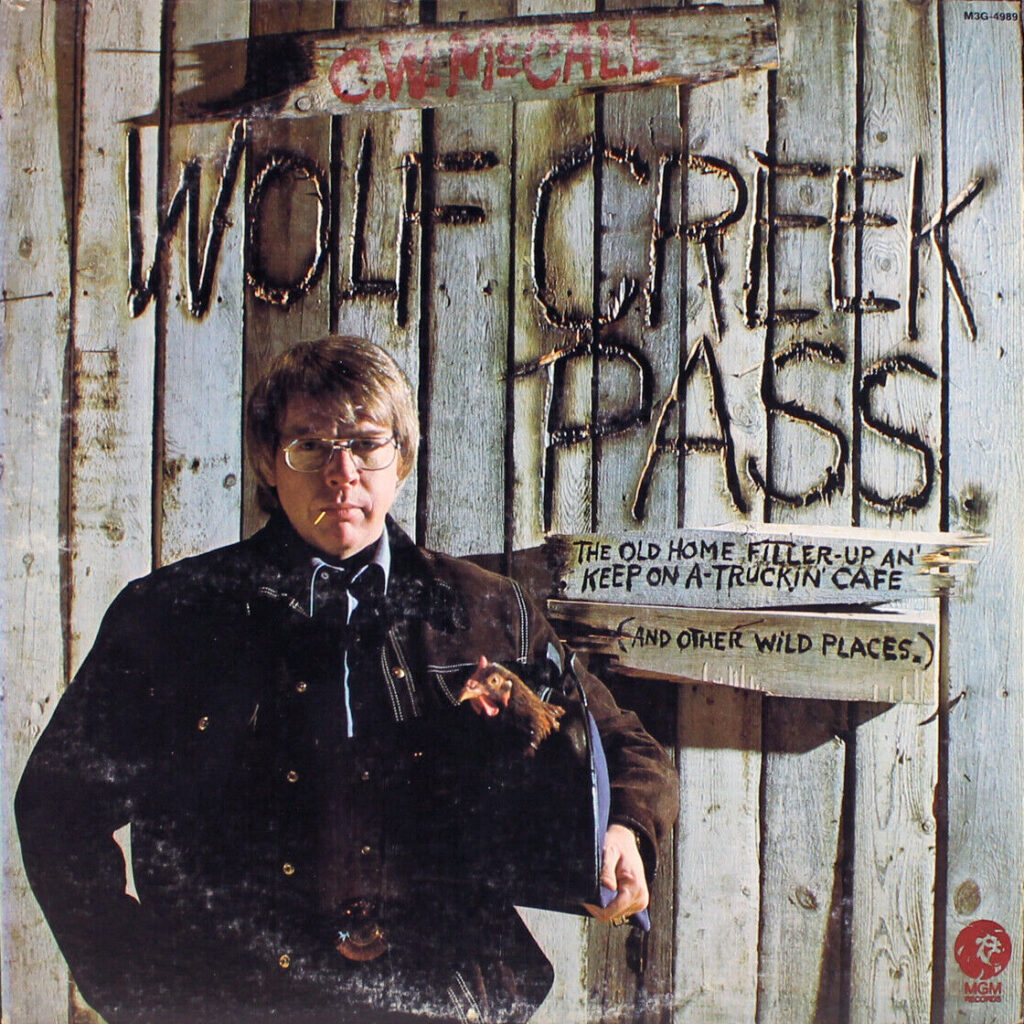

The B&J staff was busy with other projects at the time, so Fries took on the job himself. Aiming at the sensibilities of working-class Midwesterners, he envisioned a good ol’ boy truck driver delivering delicious Old Home Bread to a down-home country diner, where a feisty waitress fed hard-working people wholesome food all day long. And there would be a song, too —after all, what worked for Union Pacific would work for the Metz Bakery, too, no? The waitress he named Mavis, after a memory of a server from his own youth — but what to name the heroic trucker? He glanced around the room and saw a copy of McCall’s magazine, and in a stroke of genius, added “C.W.” — for “country & western” — and C.W. McCall was born.

At just about this time Fries met a young musician named Chip Davis, who was fresh out of the University of Michigan and had toured the country with the Norman Luboff Choir and as a drummer in a traveling production of Hair. (Talk about polar opposite gigs!) Fries asked if Davis would be interested in helping him write some commercial music and the younger man was happy to take the job. Together they wrote a song called “The Old Home Filler-Up an’ Keep-On-A-Truckin’ Cafe.”

The actor hired to play C.W. McCall in the commercial had too high a voice for the material, so Fries — a natural baritone — sang it himself, and something clicked.

The resulting commercial was so popular that the Omaha daily newspaper started printing a schedule of what times it would air. Numerous subsequent spots were produced with the same actors, each featuring new lyrics to the song to accompany the visual narrative. The campaign won a Clio Award for Best Overall US Television Campaign for 1973 — putting Bozell & Jacobs in the spotlight like never before.

One of the companies that came knocking in the wake of this success was MGM Records. They weren’t looking to hire an ad agency, though — they came to invite Fries & Davis to Nashville to make a record. The men were caught off-guard but happily obliged, cutting a single-length version of the bread commercial song, and were shocked when it made the Billboard country Top 20, peaking at number 19. MGM came back around, this time asking for an album — but Fries was skeptical, as it had never been his intention to become a recording artist and he didn’t really know how to go about it. The label told him to just write nine more songs, so he and Davis sat down and did just that.

The resulting LP went to number four on the country album chart and spawned two additional hit songs, including “Wolf Creek Pass,” — which not only went to number 12 on the country singles chart but actually entered the Top 40 of the Billboard Hot 100. (This single, backed by the lost-dog saga “Sloan,” was my most cherished 45 as a child.) As few outside the Nebraska/Iowa television market had seen the Old Home Bread commercials, it was Fries, and not the actor in those ads, who came to be recognized in the general public as C.W. McCall. Most people never knew he was playing a part.

As McCall, Fries’ signature vocal style was more spoken than sung, his deep, froggy drawl a natural fit for the character, who was sketched out as a wise, good-humored son of the soil. “Recitations” — songs in which the singer speaks over an instrumental backing — were old hat in country music by this time, but nobody since LeRoy Van Dyke had shown such acrobatic facility on the mic. McCall’s “Classified,” which hit number 13 on the country chart, showcased this dexterity:

The suits at MGM Records were happy as pigs in shit.

A second LP, Black Bear Road, followed in short order. The title cut got a fair amount of airplay, and almost made the Top 20, but it was the second single released from this record, “Convoy,” that would make C.W. McCall a household name.

“Convoy” told the story of a parade of outlaw truck drivers rolling across America in protest of numerous issues that vexed real-life truckers of the day, including the then-new 55-mph national speed limit, industry practices that forced drivers to falsify their logs to indicate they were adequately rested, toll roads, weigh stations, and so on. It was, in short, not the kind of record one might imagine being played on pop radio. And yet “Convoy” went to number one not only on the Billboard country chart, but also the US Hot 100 and the pop charts in Australia, Canada and New Zealand. And on the strength of the big hit, Black Bear Road went to number one on the country album chart — and number 12 on the Billboard pop album chart.

America was in the thick of the CB radio craze — a sort of analog predecessor to social media — and even big city folk found the homegrown slang of citizens-band radio culture seeping into their own speech: “Ten-four, good buddy!” “Put the pedal to the metal!” “You got your ears on?” On both the big and little screen there were suddenly all manner of trucker-themed movies and series: Movin’ On, BJ and the Bear (starring Greg Evigan and a chimpanzee), White Line Fever, Every Which Way but Loose, Smokey and the Bandit, Breaker! Breaker! (Chuck Norris’ first starring role), The Great Smokey Roadblock (with Henry Fonda, Susan Sarandon and Robert Englund), High-Ballin’ and others.

In 1978 director Sam Peckinpah — cashing in more than a little on the rise of trucker chic — made a major Hollywood feature film based on “Convoy,” starring Kris Kristofferson, Ali MacGraw, Ernest Borgnine and Burt Young. Though Peckinpah had directed such iconic works as The Wild Bunch, Straw Dogs and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, it would be Convoy that proved the biggest hit of his career.

Fries/McCall continued releasing singles and albums through 1979, with sporadic activity thereafter. His last stab at a hit came in 1985, with a comedic take on the George Brett “pine tar” incident; the self-released seven-inch single is a rare bird these days. All in all he made 12 appearances on the country singles chart. (His longtime partner Chip Davis found success elsewhere — with his own project Mannheim Steamroller.)

In 1986 Fries was elected mayor of Ouray, Colorado, an office he held for six years. During his tenure there he led a nationwide campaign to raise awareness and money toward refurbishing downtown Ouray, which had been badly damaged by a fire. His efforts were successful in not only revitalizing the little mountain town but making it a much larger tourist draw. To this day there is a theater in Ouray which still shows a modernized version of Fries’ epic multimedia presentation San Juan Odyssey — which in its original format required five screens and no fewer than fifteen slide projectors.

Bill Fries, Jr. died on April Fool’s Day, 2022 at the age of 93, leaving behind a remarkable career as an ad man, musician, civic leader and storyteller. His work, such an indelible component of 1970s Americana, crossed so many social barriers that even today, just the word “convoy” still serves as a shorthand for that time and place. And for me personally, his voice was such a ubiquitous childhood presence that he always felt like an uncle to me, and I’m glad to have been there in just the right time and place to have heard it.