Genny was ready for bed. She labored to swallow each of her evening pills in turn — one to calm her nerves, one to prevent back spasms, one to ease her all-over discomfort, one to help her sleep. She couldn’t get them down with water so I trotted to the kitchen and poured a couple ounces of my Diet Dr. Pepper into one of her 1970s-era insulated plastic cups and brought it to her. Something about the carbonation seemed to help her get her meds down, and bringing her a little soda pop had become an almost nightly occurrence.

She wobbled haltingly to her feet, bracing herself with one hand on her footstool and the other on the handle of her walker. I asked if she wanted to try to walk the perhaps 20 feet to the bathroom on her own feet, or preferred me to push her in her wheeled transport chair. She opted to be pushed. I brought the chair over to her and helped steady her as she turned around, very slowly, finally plopping down with all her weight, heaving a great sigh. As I rolled her out of her bedroom door toward the bathroom, she shook her head a little and spoke.

“I wish I’d go to sleep and not wake up.”

She said something like this multiple times a day, every day, and I was accustomed to hearing it — but this time her declaration of resignation was tinged with something new, a sort of spent and airless frailty. She sounded like she really meant it.

I stopped pushing and leaned forward and put my arms around her from behind.

“I know, Grandma,” I replied. “I’m sorry you’re suffering.” She clasped her right hand gently over my arm and leaned her head against mine and we were quiet together for a long moment. Finally I straightened up and rolled her to the bathroom, where I had already got her toothbrush and glass of water ready. She couldn’t stand without holding onto something, so she had taken to brushing her teeth on the toilet; I helped her get her gown up, and her disposable drawers down, then guided her awkwardly onto the pot and left her to her business until she called.

Afterward we went through the considerably tedious nightly choreography of getting her out of the chair and into her narrow twin bed, concluding as always with a little goodnight peck on the lips. It was maybe 10:30 when I turned out her light.

I went into the living room to watch TV, but before long I heard Genny muttering to herself and went in to see what was the matter. She just couldn’t get comfortable. She insisted there was a “hump” in the middle of her twin bed, but I assured her that couldn’t be the case, as we had just sourced both a new mattress and box springs because of the perceived “hump” in her old ones. The simple matter of fact was that she didn’t have the strength to turn herself over, and she felt like she was going uphill any time she tried.

Within the next couple hours she pressed her call button twice, summoning me into her room to again try to help her get situated comfortably. Finally I nodded off on the couch, and when I awoke again with the TV still on it was around 2:00 am, and I could hear my grandmother snoring in her room.

I breathed a sigh of relief, as she had been having terrible trouble sleeping over the previous month or so. She would page me up to five or six times in the middle of any given night, sometimes needing to go to the bathroom or take a Tylenol, sometimes just confused because she was mixing up her dreams with her waking life. She would think I was her late husband, or my father, or a stranger, or that she was somewhere or somewhen else. And after these long restless nights, she would spend much of the following day sleeping in her rocking chair.

For now, though, she was sawing logs and I was grateful. By 2:30 I was out, too.

The next morning was a Sunday, and at around 8:00 the sun peeked through the blinds in the living room, waking me up on the couch, where I slept each night — in part because I habitually fell asleep with the TV on, and in part because it was close to Genny’s room. I peeked in on her and saw her long white hair spread across her pillow. She had slept through the whole night! A minor miracle.

At around 10:00 I went in to see if it was warm enough in her room. It was my policy to let her sleep, always, but if I didn’t wake her up by about 10:30 in the morning, she would complain that she was letting the whole day go to waste. (I found this amusing, as her entire day typically consisted of sitting in her chair watching reruns of old game shows, but I indulged her wishes.)

It was then that I noticed she was sleeping face-down rather than on her side as usual. I reached out a hand to gently shake her shoulder to wake her, and found her curiously cold to the touch. I tried to roll her onto her side but horror washed over me as I felt the resistance of her stiff body. I gasped and let go, recoiling in shock. I stared at her motionless form, looking for any sign of breath, for a long minute. There was none.

After nearly a century, my grandmother, Genny Tally, had gone to rest. Her wish had finally come true.

Genny was the first of eight children born to John Wyant and Lillie Mae Dunbar of Newkirk, Oklahoma, a Cherokee Strip town just south of the Kansas border. John had been born there, too, before the “Indian Territory” had formally become a US state. One day in his early 20s, while working as a delivery boy for a local grocer, he had the good fortune to see a man standing outside the Santa Fe railroad depot, and — half-jokingly — asked if the fellow had any work for him. He was told to come back after lunch if he wanted a job. John did just that, and fell into a career that would last until he retired in the 1960s.

The first thing John did when he started making a regular salary was to build a house from his own plan. There was not only electric wiring throughout the place, but indoor plumbing too — a luxury not enjoyed by the majority of his neighbors. He married his sweetheart Lillie, and before long, the young couple became fruitful and multiplied.

In 1923 came Genny, and then the other siblings, every two years like clockwork — Clyde in 1925, Mary Helen in 1927, twins Leon and Louise in 1929, Imogene in 1931, and the second set of twins, Ola and Opal, in 1933. Two of them succumbed to childhood illnesses: Leon at three months of age, and Mary Helen at four years. I have seen just a couple blurry snapshots of Mary Helen, and there exists but one lone photograph of poor Uncle Leon — a studio portrait taken after his death, swaddled in his tiny baby coffin.

The other six Wyant children, however, proved remarkably robust, and all would go on to live into their seventies, eighties and nineties.

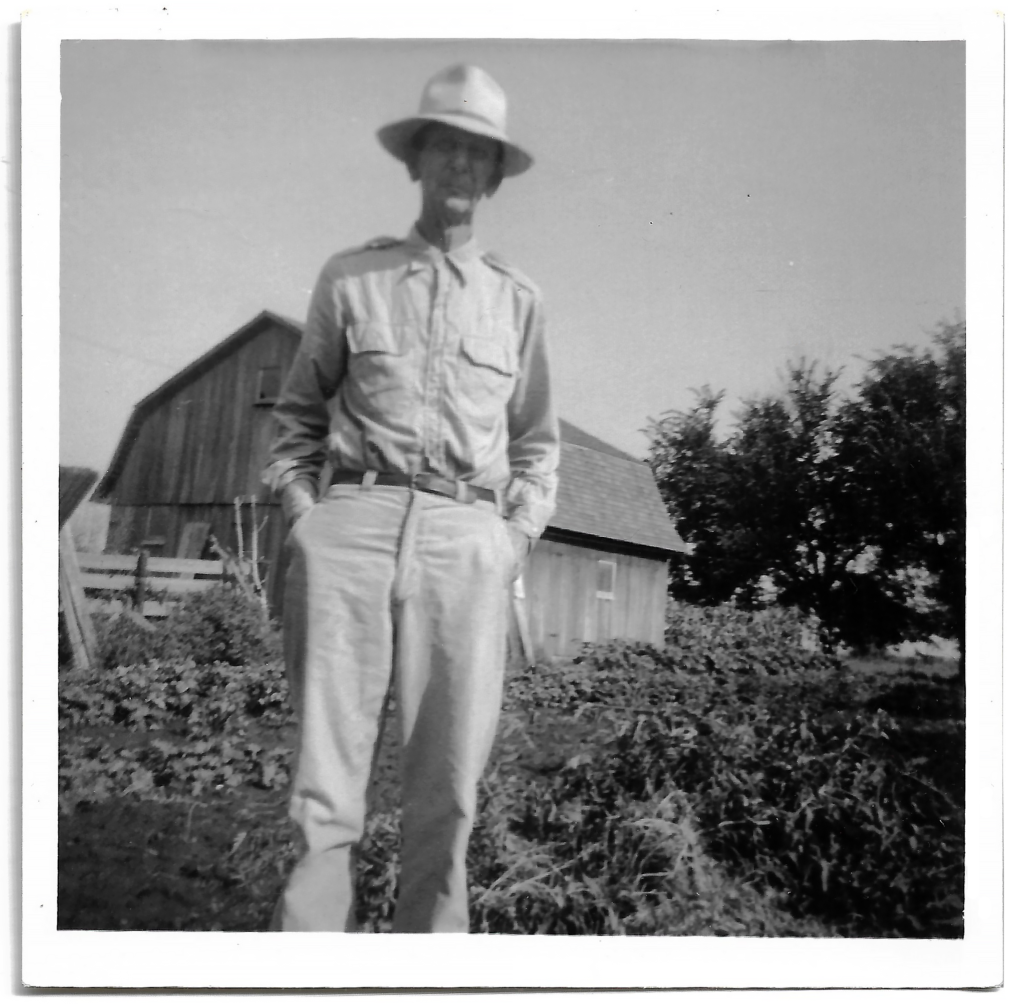

Genny often marveled at how her father juggled so many responsibilities in those days. He worked six or seven night shifts a week at the depot — this was before unionization — and back at home, he kept bees, raised livestock, tended an extensive garden and a small orchard of fruit trees, dithered in woodworking and kept an eye on his flock of children. He was a busy man indeed.

John was a frugal man, too — “tight as Dick’s hatband,” as Genny would put it — yet splurged when it came to his truest love: music. He bought a deluxe model Victrola, a player piano, an expensive radio, and many, many records. The old man enrolled young Genny in piano lessons, assuming her long, fine hands meant she would be a natural, but she preferred to listen — and dance — rather than play.

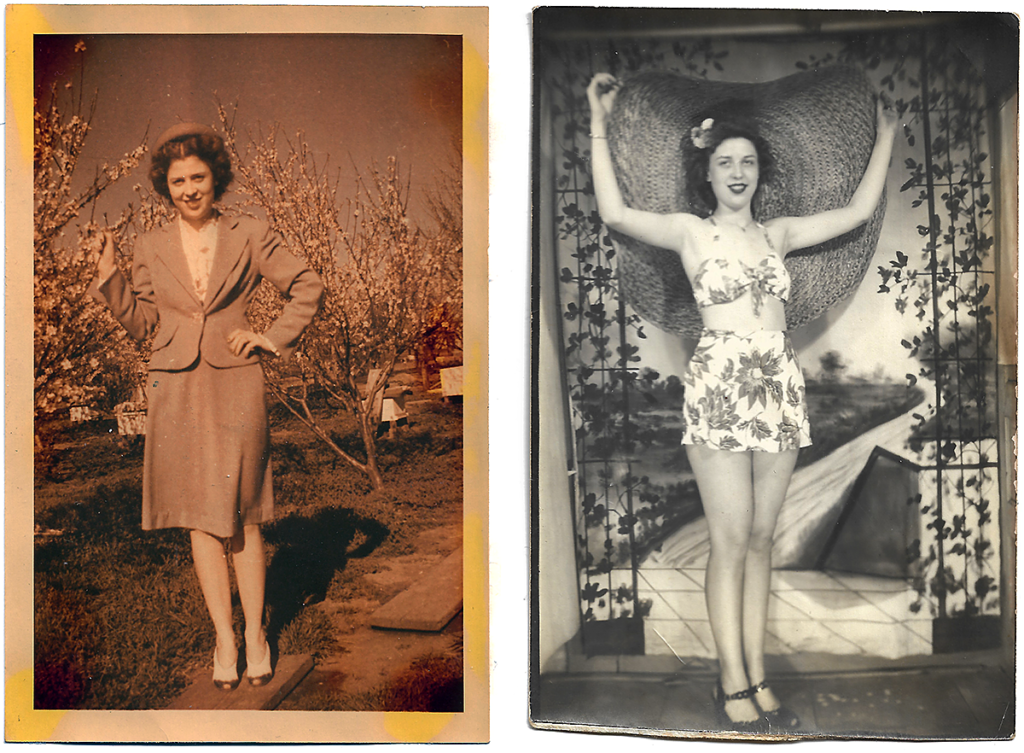

Genny was always creative, and known for being painstakingly precise in her work. As a young girl she would beg the neighbors for their old Sears & Roebuck catalogs, from which she would laboriously cut out figures from the fashion pages to use as paper dolls. Later in life she would go on to make most of her own clothes, always with an eye for beautiful fabrics, clean lines and splashy colors — and she took pride in filling her home with tasteful furniture that she refinished and reupholstered herself, too, to a meticulous standard.

It should be no surprise then, to learn that Genny was a childhood penmanship champion as well, and up until the last months of her life she boasted some of the most fluid, florid, lovely handwriting you are likely to see in the modern day. But as a child she bemoaned her long, unwieldy name. “Florence Genevieve Wyant,” she said on many occasions. “I had to spell all that. Why couldn’t I be like the other girls in my class with names like Betty or Sue or Jane?” Just as most of her sisters did, she chose to go by her middle name, but shortened it to the unusual “Genny with a G-E.” Over the years it would often be misspelled as Jenny or Ginny or even Genevee, but she took it in stride.

The Tally family of Newkirk was an even bigger brood, and to be honest I am not entirely sure how many of them there were. My grandfather was Troy Tally, and most of his brothers died either before I was born or when I was young, so I don’t really remember any of them except the irascible Harold, and just vaguely, Bill. Troy’s sisters, on the other hand, would live long and remain close to my grandmother always. There was Tinie, and Beulah, Ernestine and Edna — like the Wyants, another fine bunch of “cornfed” Okie gals.

In the summer of 1939, just weeks before Genny’s 16th birthday, she and Troy — himself not quite 21 — secretly eloped across the state line to Wellington, Kansas and were married. They returned to their respective parents’ homes and said nothing. A couple days later, John Wyant came home fuming, looking for Genny.

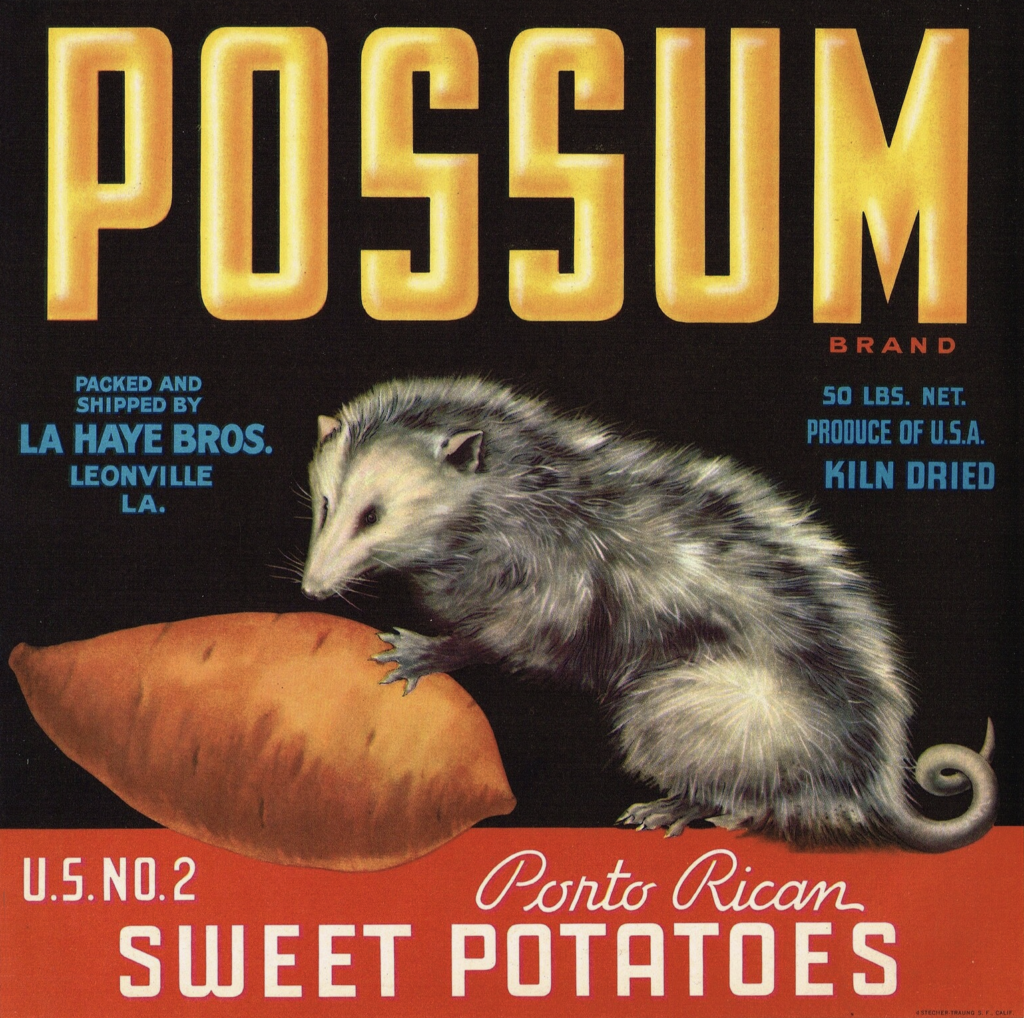

“What’s this I hear in town about you marrying that Tally boy?” he barked at her in the kitchen. “What are you gonna live on, possum and sweet potatoes?”

But his anger was short-lived, as he quickly found it useful having Troy around to help out with his many chores. He even managed to get his new son-in-law a plum desk job at the Santa Fe depot, provided the younger man learn to at least rudimentarily operate a typewriter.

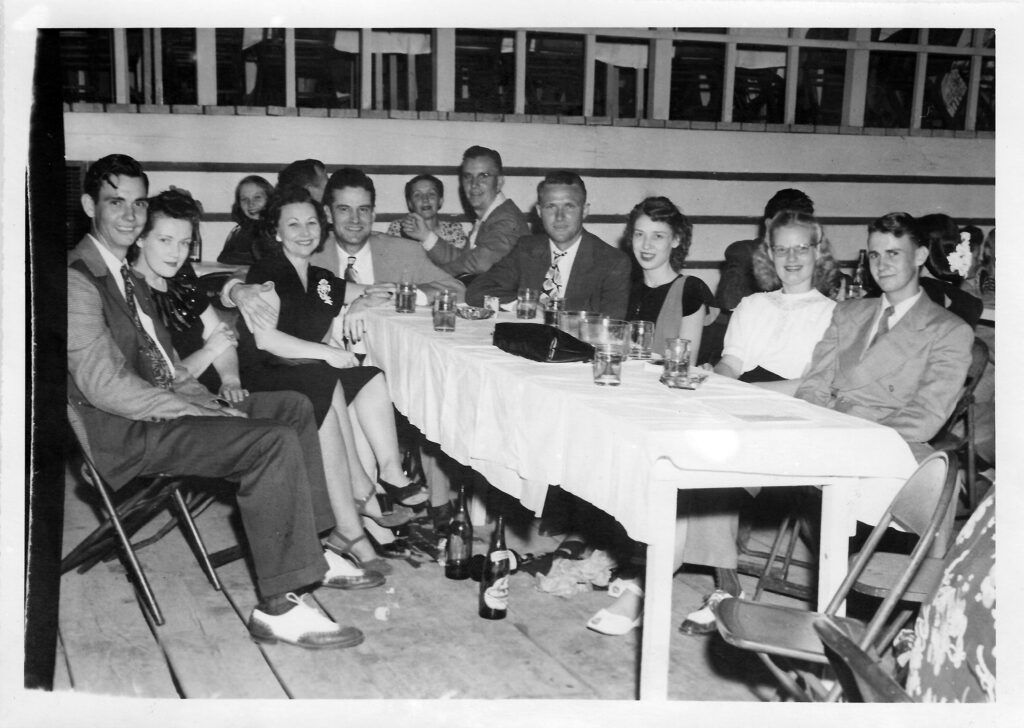

And so began married life for Troy and Genevieve. He worked at the depot, and she kept house, and sewed, and canned vegetables, and did the shopping, and all the rest. In their leisure time, the young couple occupied themselves with rollerskating, lake outings, drinking home brew, and — chief among their pastimes — dancing. They would hitchhike down long stretches of barren Oklahoma highway to attend performances by Bob Wills & the Texas Playboys and other regional favorites.

One night, drunk and exhausted after a night of dance floor revelry, Troy and Genny stood with their thumbs out on the narrow shoulder of a dark road, hoping for a ride home. A pair of headlights appeared on the horizon, and the driver was kind enough to pull over for the bedraggled young couple.

“Where are you kids going?” asked the middle-aged man behind the wheel.

“We’re trying to get back to Newkirk,” Troy said.

“Well, do you mind driving while I get a little sleep?” the driver asked. “I’ve been on the road all day and have a long way yet to go.”

Troy was surprised but agreed, and before another minute had passed, the stranger was fast asleep in the backseat of his own car with this random intoxicated young Okie behind the wheel, hammering it full-tilt down the pitch dark highway. When they arrived home in Newkirk, Troy roused the fellow, pointed the way back to the main road and thanked him for the lift. The stranger rumbled off into the night, and the exhausted young couple stumbled inside and fell into the sweet embrace of their own bed.

It must have been around 1942 when Troy got transferred from the Newkirk Santa Fe depot to the company offices in Perry, Oklahoma, some 50-odd miles to the southwest. He and Genny loaded all their belongings onto a boxcar — a perk of being a railroader — and drove their car down to Perry to check in. When they got there, Troy was gobsmacked to find a telegram waiting for him — from the area draft board. They didn’t even take their things off the train. Genny went back to Newkirk and Troy reported to the Army.

Before being deployed overseas, Troy was assigned first to a base in Alabama, and then to California. As soon as she was able to, Genny followed him to those places, taking jobs tying sausages and sewing tents and uniforms for the war effort. In California they rented an apartment from a magnanimous Italian named Bonano, who showed Genny how to make a rustic spaghetti with roast beef the way his family always had back in the old country. The gentle paesano would no doubt be honored to know that Genny would go on to make her spaghetti that way for the rest of her life.

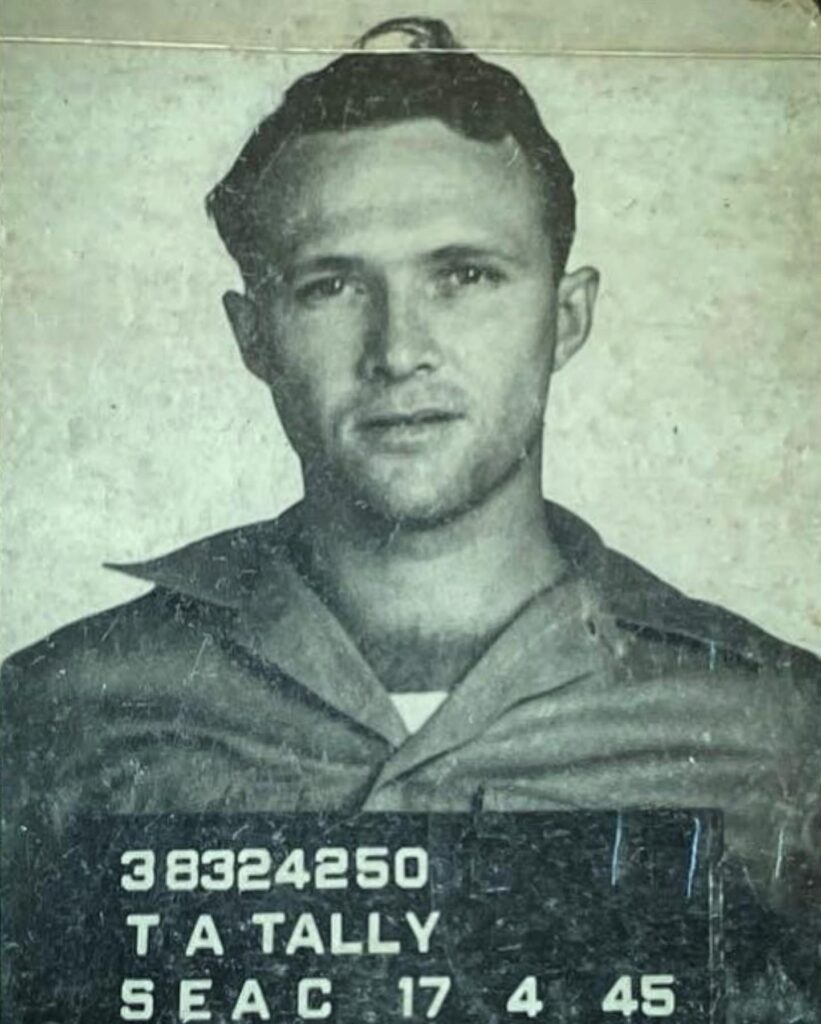

In the Army, Troy’s civilian position as a clerk bore an unexpected bonus; rather than being handed a rifle and shipped off to Europe like so many of his fellow Okies, he was instead assigned to a series of military offices in Australia, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and India. He was blessedly spared from direct exposure to many of the horrors of war, and made the best of his time serving in a tropical paradise. At one point he even lived in a barracks with a pet monkey, for which someone sewed up a little uniform.

Not long after Troy came back from the service in 1946, Genny received a letter from a young woman in Nebraska. She claimed that she had been Troy’s girlfriend overseas during the war, and that she was pregnant with his child. Genny wasn’t having it. She got out her stationery and wrote in reply a letter that began with, “Dear Sucker.” She thanked the other woman for taking care of her man while he was overseas, then curtly dismissed her, telling her in no uncertain terms not to contact them again. And you better believe that was the last of that.

Troy went back to working on the railroad, this time in the Arkansas City, Kansas office, just 12 miles north of Newkirk. He and Genny lived in a series of apartments around town and attempted to start a family of their own, but their efforts were thwarted when Genny suffered a serious uterine ailment that led to her having a complete hysterectomy. Their subsequent attempts to adopt a child were routinely denied for several years.

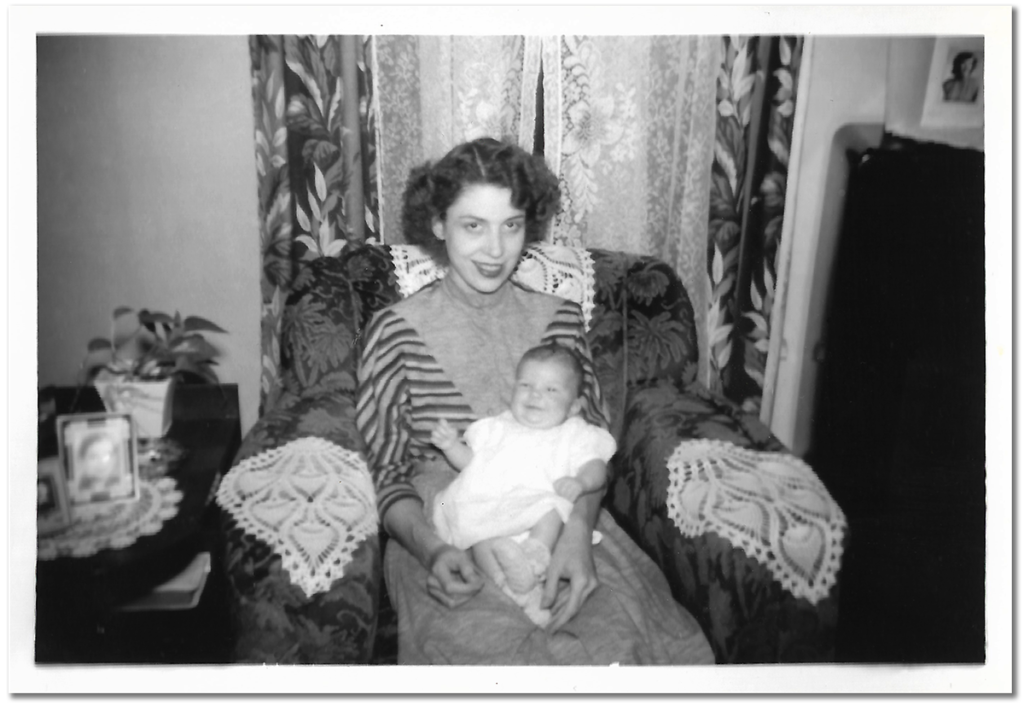

On Sept. 1, 1950, they closed the deal on a modest house of their own, a little place on the northwest side of town, built in the 1920s. And three weeks later, out of the blue, they received a phone call with word that they had been approved to adopt a newborn baby girl. Jeanetta Lynn was born in Kansas City, at a hospital dedicated to unwed mothers, and shortly thereafter came to 1015 North 8th to stay.

Genny was never a religious person, but she got it in her head that having a baby meant they ought to start going to church, as that seemed to be what people did. She and Troy chose to join the Episcopalians, in no small part because the people they knew from that congregation were not holy roller types — and also it didn’t hurt that their church in Ark City boasted a lovely gathering area where people smoked and drank coffee after Sunday meetings, and an outdoor playground too.

The Tally family was living the American dream.

And I mean they really were. Troy’s job provided a solid middle-class salary, and was low-stress enough that he spent a good portion of many of his workdays at his other “office” — the old Puritan pool hall a few blocks from the Santa Fe station, and right next door to his bank. Genny occupied herself maintaining an immaculate home and doting on her precious child, Jeanetta. And even with the kid along for the ride, Troy and Genny still socialized regularly with their old gang, playing cards or dominoes and having cookouts.

They enjoyed church functions — including the legendary Episcopal Bean Feed at which all the men got so drunk while working the door that they were scarcely able to take tickets. And in the summers, they started making annual trips to Grand Lake o’ the Cherokees in Oklahoma, along with various friends and family. The men would fish and putter around on the lake in boats; the women would go into the town of Grove to shop or over the Missouri line to swim in the crystal clear Elk River at Noel, then cook massive dinners for the whole bunch in the evenings.

And so passed the ’50s and much of the ’60s.

But it wasn’t all sunshine and roses, either. Genny and Troy quarreled over his gambling and his flirtations with other women; the former he hid from her and the latter he did not. She accused him of laziness around the house as well. In one famous family story, the washing machine died and she told him they needed a new one. “Well,” Troy suggested, “you can always just go to the laundromat up the street.” Genny looked him square in the eye and replied, “OK, that’s fine. We’ll go on the weekends when you’re off work and you can come with me.”

She got her new washer.

And then there was Jeanetta. She was a handful from the get-go, always getting into things that were better left alone, and always lying to cover her tracks when she was busted. This behavior was there all the way back to the beginning, and would continue for the rest of her life. “Jeanetta was a darling little girl,” Genny would recall wistfully in her later days. “I don’t know what I did wrong.”

But I don’t think it was anything anybody did or didn’t do. I believe that Jeanetta — my mother — would have been who she was, regardless of where or how she was raised or by whom. She couldn’t help herself. She didn’t mean any harm. She simply lacked the ability to stop herself from acting on her worst impulses, which in turn caused endless turmoil for herself and those around her until the day she died. And all along, Genny was right there to pick up after her many messes.

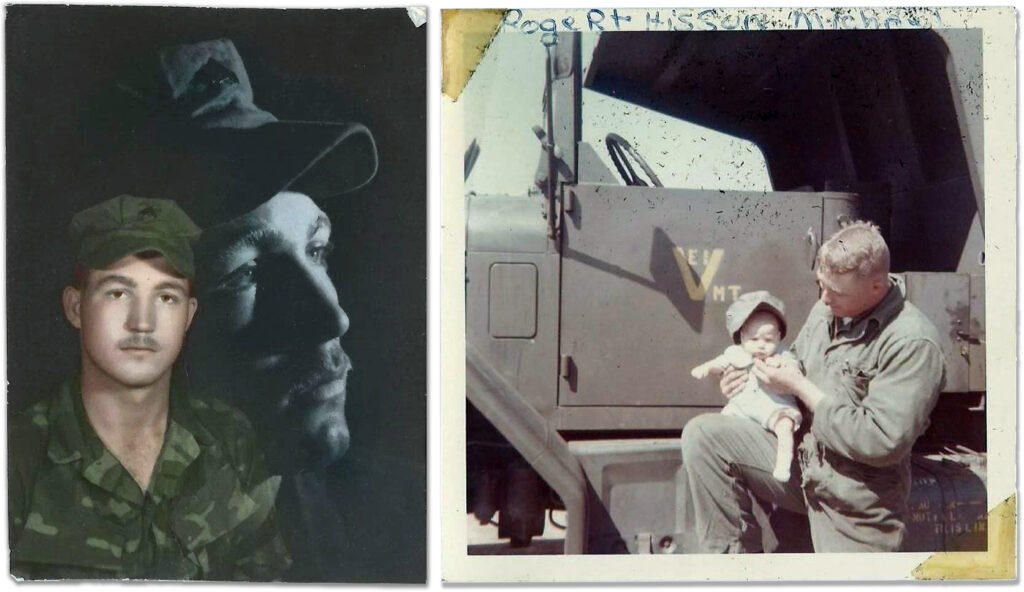

Jeanetta dropped out of school at 16 to marry her boyfriend, my dad, Roger, a tough but sensitive kid from a hardscrabble background. He was a couple years older and just graduating high school. I have to admit I wonder what drew them together in the first place, but thinking back on my own early dating life, I recall that such matters are seldom rational. At any rate, like her mother before her, Jeanetta suddenly found herself a teen bride — and not long thereafter, a military wife too.

Roger joined the Marines during the height of the Vietnam conflict and while he and my mother were living on the base at Camp Pendleton in Oceanside, California, I was born. A few months later they sent him off to the war and my mother returned to Ark City, with me in tow.

Genny was over the moon to have a grandchild. Among all her siblings, she was the first grandparent and she made a full-time job of spoiling me. She sewed many cute baby outfits for me and was forever pulling out the old Polaroid Land Camera to take my picture, at a time when film was an expensive commodity. My earliest memories are uniformly of her house on 8th Street, and come from the time after my mother and father split in 1972. By then my little brother Chris was on the scene, too, but my father was rapidly disappearing from my view after losing visitation privileges in a time when neither father’s parental rights nor their value to their children were regularly recognized by family courts.

What’s funny is that I don’t remember my mom as a mom figure, ever. It was always Genny. Jeanetta was much more like a flighty, unreliable older sister, or a fun-loving but flaky aunt, than anything like a mother. Always. I found in Genny the mother I was missing, and she found in me a second chance to raise a bright, cute, and perhaps most importantly, well-behaved child.

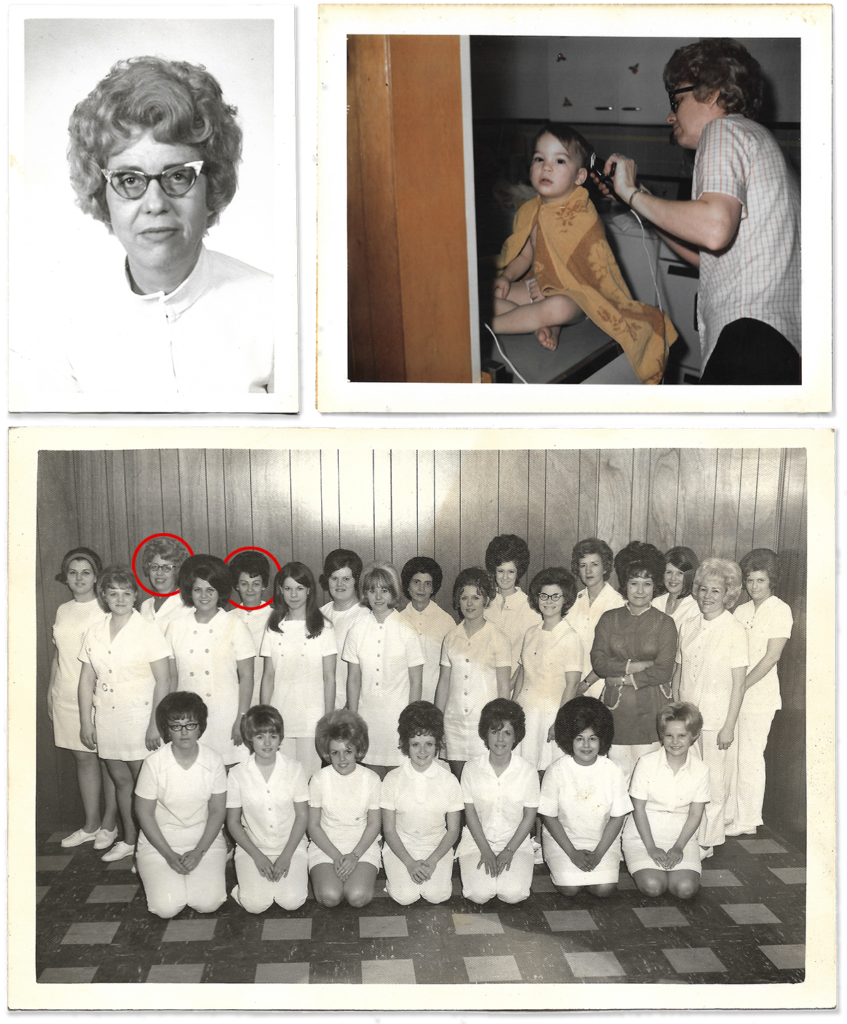

Around this time, Genny and her sister Louise both enrolled in the local cosmetology school, in order to learn how to cut and style hair. They figured the money they spent on tuition would be more than made up for over the years as they gave one another hairdos and cut all their family members’ hair as well.

“Hell, you’ll never finish,” Troy scoffed when she told him her plan. This only served to double her resolve. She and Louise both finished their courses of study and were issued state licenses.

“I wanted to shove that license up his ass,” she recalled years later.

I must have been only three or four at the time, but I remember visiting her and Aunt Louise once at the old hair school, in the basement of a building — now a mortuary — just up the street from her house. A gaggle of women in smocks fawned over me and pinched my cheeks and cooed about how cute I was and Genny beamed twice as hard as my mother did. She went on to cut my hair until I decided to grow it out as a teen. To this day I still have her case of cosmetology supplies, including combs, scissors, clippies and tons of curlers — and her textbook, too. In fact, I have been using her electric clippers to trim my beard and shape up my hair for much of my adult life. So in the end, that schooling really did pay off.

Jeanetta remarried in 1975, and she and my brother and I all moved in with the new stepfather, David, just four blocks down the street from my grandparents’ house.

The turbulence of life with my mom and David are of course well-documented elsewhere in these memoirs, so I will suffice it to state here merely that things were very, very bad for me and Chris. Neither Genny nor Troy could stand David, but they did their best to be civil. If they had known two percent of what was going on, I am sure they would have lost their minds — but I never told them. For all the day-to-day horror of our lives at the time, I still didn’t want them to be mad at my mom.

By my fourth grade year in school, Chris and I had started spending every Friday night over at the grands’ house. I remember having PE class on the playground at Pershing Elementary (RIP) in the late afternoon and seeing Genny’s long chiffon yellow Oldsmobile parked along the curb there on 2nd Street. How my heart fluttered! I would get to hang out with Grandma and watch TV and have whatever I wanted for dinner and probably even get a whole glass of Coca-Cola! And most importantly, there would be no Mom, no David. Even though by then the two of them had separated, David kept coming around and making things worse for me and Chris. Those nights at Grandma’s were true godsends.

I was long accustomed at this point to being left alone in charge of myself and my little brother, and was surprised when my mother told me one day that we were going to be staying over with a babysitter on some upcoming overnight shifts she was working at the local Sambo’s restaurant. The lady, who had pictures of the Pope and JFK on the walls of her living room, was old and rather grumpy, but she let us watch what we wanted on TV and fed us name brand cookies, so I was OK with her.

The morning after the second or third time we stayed over with her, sleeping on pallets on the living room floor, my mom didn’t come pick us up. The sun grew brighter and brighter in the sky and the old lady got madder and madder.

“Maybe your grandparents should take you boys away from your mother,” she said out loud. “I’ll be glad to help them do it.”

It was a punch in the gut. The way she said it made it sound like this proposition was already hanging out there in the air — and yet no such possibility had ever even remotely occurred to me. But just a split-second after the surprise came a tiny warm glimmer of emotion — was I daring to hope!? It didn’t last. I was just as quickly overcome with shame, as the moment I heard it suggested that I might be taken from my mother, that instantly became all I wanted. What kind of kid did that make me? I felt sick.

That Christmas Eve we had dinner at my grandparents’ house, and as we were finishing our meal, a knock came at the door. It was David. My mother had invited him over, neither of them fully grasping just how unwelcome he had made himself there by that time. My grandfather told him to leave but David unwisely chose not to. The two men snapped back and forth at one another and before I knew it, they were grappling with one another in the minuscule kitchen. My mother and grandmother both squawked at them to stop as Chris and I sat frozen in terror at the dinner table.

The action came to a sudden stop and there was Troy, once an incorrigible brawler, clutching a paring knife in front of him, a glare in his eyes I had never seen before. David was only a couple feet away, right next to the dish drainer, and he snatched up a butcher knife and for just a second I was sure there would be blood.

But David left, and the police came to the house and gave my mom, Chris and me a ride home in a squad car. I was still young enough to worry that we wouldn’t get in bed in time, and maybe Santa would skip our house.

It was clear Genny was worried about us. For a while we were functionally homeless, crashing on the floor of a house on the south end of Ark City with some hippie friends of my mother’s. My grandpa dutifully drove across town each morning to pick me and my brother up and take us to school, as my mother no longer had a car. He and Jeanetta argued bitterly and frequently and after a while they barely spoke at all. We moved into a low-income housing project right next to my old elementary school, Adams, which itself was only about three blocks from Troy and Genny’s house — close enough that I could walk over there any time I wanted. And I did, a lot.

In the middle of my fifth grade year of school, just weeks after my grandfather retired from his life of service on the Santa Fe Railroad, my mother instructed me and and my little brother to load anything we wanted to keep onto the wood-staked Radio Flyer wagon she had borrowed from a neighbor.

“We are moving back in with my folks,” she explained.

I was stunned, shocked, exhilarated! In no time at all we had packed our modest collection of clothes and books and toys, and then there we were, walking over to Troy & Genny’s house to stay. I don’t know that I had ever been happier than I was in that moment, my ears filled with the sweet sounds of gravel crunching under my feet and the squeaking wheels of the toy wagon.

My mother told us to go on ahead of her into the house, and when we did, she walked away without a word and did not return.

I would live at my grandmother’s house for the next nine years.

Chris and I settled in quickly. I was in heaven, finally in a place where there was food and electricity and water every day, heating and air conditioning, clean clothes — and just so much love. Nobody hit me, nobody threatened me, nobody got sloppy drunk or drugged themselves to the point of uselessness, nobody came into my room in the night to perpetrate horrors upon my body. My prayers had been answered.

But as happy as I was, Chris took things tougher. While my feelings toward Jeanetta had slowly been transformed from love to something closer to repulsion, Chris and she shared a profound emotional bond. In fact, I often thought they were more like twins than mother and child. Jeanetta came around less and less as she spent longer stretches of time crashing with some of her trashier friends, and when she did come, she and Troy often clashed. Chris would throw fits as she turned to leave, hurling himself bodily at her and locking both arms around her waist, begging her to take him with her. It was heartbreaking. Her visits became even fewer and farther between.

My grandparents, robbed of their retirement years, became our legal guardians and full-time parents.

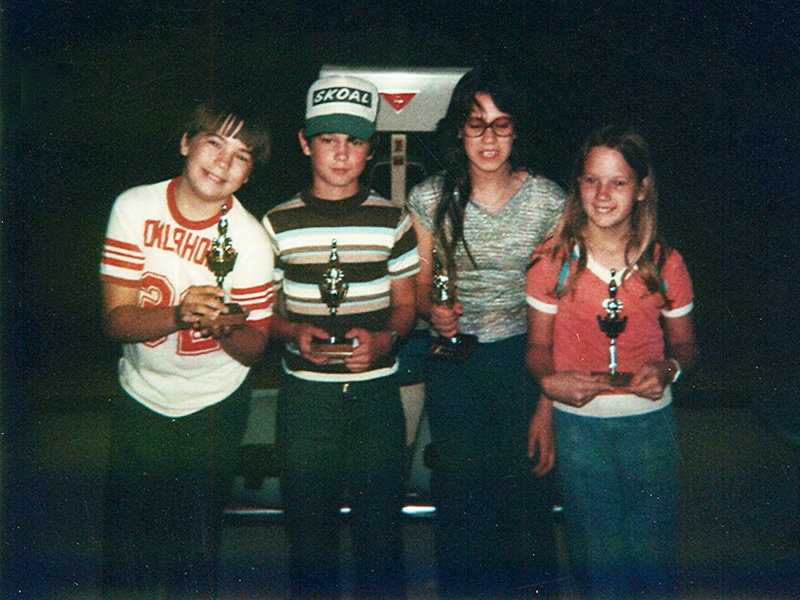

Time went by. I got a paper route and bowled in a Saturday morning youth league, both of which Troy helped me get into. In the summers we went to Grand Lake for a week with him and Genny, and there were still plenty of nights back at the house when friends and family would come over for cards or dominoes, just as they had done since all the way back in the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s. Chris and I went to school like everybody else. The scars from my prolonged trauma were still there, of course, but I wasn’t getting so many new ones. I felt (a little) more like a normal kid.

My mother went to jail for a little while after forging checks stolen from Genny’s purse. Her assumption that her own parents would not press charges against her proved to be mistaken. I was embarrassed, knowing that everybody in town read the Police Notes in the local newspaper — but relieved that a jail sentence meant she wouldn’t be showing up randomly, upsetting Chris and stirring up a hornet’s nest with Grandpa.

On the morning of February 12, 1982, Troy dropped me off at the middle school, then just minutes later keeled over dead behind the wheel of his ’67 Pontiac while driving down the road. Chris was in the passenger seat, but managed to escape injury, as the car came to a gentle stop in someone’s snowy yard.

Genny was 58 years old and had been married to Troy since she was 15. For the first time in 43 years, she was alone. And she had two kids depending on her too. There was some sort of holdup with her railroad widow’s pension for a little while, and out of concern for her household income, she moved her octogenarian father, old John Wyant, into the house with us to help make ends meet. It was a hard adjustment for her, but she powered through, rarely allowing her obviously considerable stress to compromise her poise.

In the spring of that year, just a couple months after Troy’s passing, I walked down Linden Street toward Wilson Park with my tennis racket, intending to practice bouncing balls off the big backboards at the courts there. I had joined the tennis team at Ark City Middle School — though they never let me compete in a single match — and was really trying to get better, albeit fruitlessly. As I passed the house of one of my mother’s druggy BFFs I saw the Pontiac that Troy had died in sitting in their driveway. Just then Jeanetta came out of the house and waved at me. She seemed to be in good spirits.

“Where you goin’?” she hollered.

“To the park to practice,” I replied.

“Well, OK, have fun! I’ll see you later.”

I returned home that afternoon to find Genny in a fury. My mother had let herself into the toolshed at the house and taken all my dead granddad’s tools, fishing poles, anything of value, loaded them into the trunk of the Pontiac, and disappeared. The car was found abandoned outside of town with an empty gas tank; the stolen goods later turned up at a disreputable local pawn shop. I would not see my mother again until much later, when we would visit her in the state prison at Lansing, where she spent several years, I think for drugs.

By this time, my father had been allowed back into my life for the first time in nearly a decade, and as I had virtually zero memories of him from before, we forged a relationship from scratch. He had remarried and had three more children, and his new wife and kids were all very sweet to me. Just when I needed a male role model the most, he showed up — and Genny and I were both happy for his return into our sphere. For the rest of her life, the two of them treated one another like mother and son, and that example was really good for me to see.

Genny attended every parent-teacher conference, took us to the dentist every six months like clockwork, bought or sewed all our clothes, and doctored us when we were ill. I had been a skinny kid when we moved into the house, but Genny made sure we had breakfast, lunch, dinner and snacks all day, every day. Chris and I chugged several gallons of fresh whole milk each week, sourced from a local dairy farmer, and I started getting fat. At least I wasn’t underfed anymore, eh?

Genny bought me my first car, a notorious lemon, and despite its many egregious flaws I appreciated it deeply. The freedom afforded by a simple automobile was so overwhelming, a gift beyond comprehension. I quit my paper route and started working a higher-paying fast food job to keep up my end of the bargain — she bought the car, I was responsible for gas and insurance, etc. I felt like I was growing up.

Through it all, I adored her, and I did my best to be helpful and avoid adding to her struggle as she attempted to navigate her post-married life with two goofed-up kids and a cantankerous old man in her care. For a long time the only static between us came as a result of my steadfast refusal to do my homework, or otherwise put in any sort of effort toward getting good grades at school.

And then I got my first girlfriend, who derived a Machiavellian sort of glee from causing friction between me and Genny. For a couple years there, I was constantly forced to choose my loyalty, and it strained my relationship with my grandmother nearly to a breaking point. I even moved out of the house and into an apartment with my girlfriend after graduating high school, but it didn’t last. I broke it off after her ongoing abuse got to be too much for me to take, and crawled back to Grandma with my tail between my legs. Genny, of course, welcomed me back with open arms.

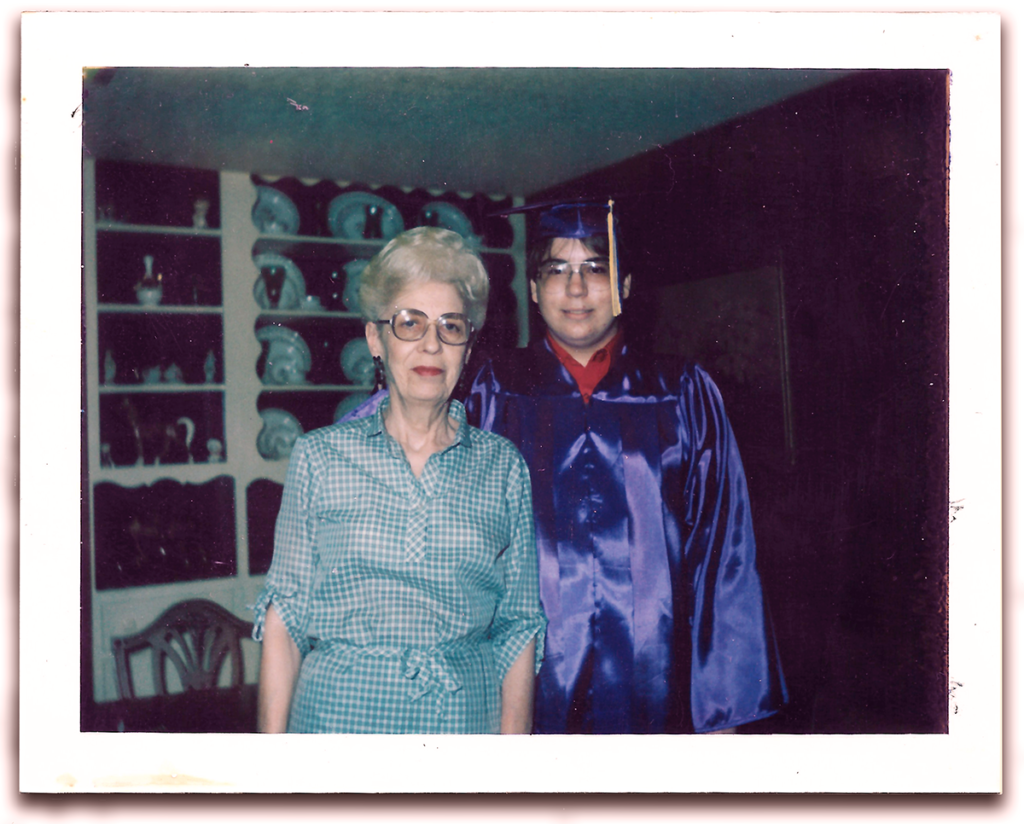

By that time I had finished one semester of community college, and dropped out of a second. I was accepted — under condition of academic probation — to Wichita State for the fall semester, and started making plans to leave Ark City. My mother had not returned to the house after her prison sentence; she had come out as a lesbian while inside, then went on to a succession of committed same-sex relationships with women in Wichita. Chris dropped out of school and moved up to the big city to live with her, and now I was going, too. By this time not even old John Wyant was around anymore, having passed at the age of 88 in 1987.

One of my buddies from high school rode up to Wichita with me and my grandmother to help move me into the dormitories at WSU. That night, Genny returned to an empty house, truly alone for the first time since 1939. Later she told me that she cried, something I had almost never seen her do.

On my first day of classes at WSU, I discovered that all my months of pre-registration and early enrollment had been for naught, as somehow the school’s computer had lost all my records and I was not listed as a student in any of the classes I had selected. And as those classes were now all full, my only hope to salvage the semester was to choose other classes in the same departments, so the credits would still count toward my degree. Within a few weeks, despondent at the experience of attending all these unwanted classes, I dropped out of school. By the next summer, I had little choice but to move back to Ark City for a while to regroup.

And of course, Genny was right there for me. I stayed with her during the weeks and helped out with the lawn and whatever other chores she had for me, and on the weekends I drove back up to Wichita to work the door at a college bar and crash on friends’ couches.

I had worried about her being too lonesome down there in the house by herself, but in my brief return to the nest, discovered that she was managing to fill her time quite well. In the mornings, one of her lifelong best friends, Ted Jones — who lived just a block away — would come over and drink cup after cup of coffee from Genny’s Bunn-O-Matic and shoot the shit for several hours. Aunt Imogene, also widowed, visited frequently after she got off work at the junior college. And Uncle Kenny, husband to Genny’s sister Louise, was on call at all times as handyman and lawn guy. She was socializing as much as ever and always had something to talk about.

In addition, Genny had joined a travel club for senior citizens, organized by her bank. She went on several budget-priced gambling junkets to Elko, Nevada, and a number of cruises, too. In fact, on the day of her 70th birthday in 1993, she was in St. Petersburg, Russia, on a cruise of the Baltic Sea. She bought me a souvenir t-shirt there, and I wore it until it fell apart.

Though I moved back to the big city for good, Genny never stopped providing me whatever type of support I needed: food, love, encouragement, money, anything. When I drew up plans to open a coffeehouse in 1992, she asked how much money I needed, and without another word, she cashed in one of her certificates of deposit and gave me $10,000 to get the place started. Juggernaut was a huge hit — but an unmitigated financial disaster, and a magnet for negative attention from city officials. We were closed within months, and I lost my ass. I was sure Genny would rip me a new one, but she knew how hard I had worked, and she went easy on me.

I was married twice, and divorced twice. Over the years I brought countless friends (and girlfriends) down to Ark City to meet my grandmother, and she almost always took a shine to them, immediately treating anybody I dragged into the house like family. Everybody was always offered a drink, and something to eat, within a minute of coming through the door. She was still her old self — gregarious but ornery. Genny was know so long for her bottomless catalog of old-timey off-color catchphrases that she was sure to drop one or more in any given conversation, often cracking up my guests. In 2000, in order to enshrine her Okie wit, I put up a website with some of her choicer sayings.

But then, with time, she started to slow down. Eventually my mother moved back into the house with her, after the last of her long-term relationships fizzled out. The timing was fortuitous for both of them; Jeanetta did more and more of the cooking and cleaning and shopping as Genny became less and less able to.

I had my first child just before my 43rd birthday; as Genny had been 45 when I was born, the age gap between her and myself was almost the same as between me and Nash. She spoiled him (and later his little brother Moses) rotten, and continued doing so for the rest of her life.

The Wyant kids started passing away, one by one. First came Ola in 2009, then her twin Opal in 2013. Louise went in 2014, Clyde in early 2019 and Imogene later that year. Genny, the first born of eight, was the last one standing.

By that time Jeanetta’s health had failed spectacularly, and she was in full-time complete nursing care in a home in Winfield, Ark City’s twin city just ten miles to its north. Genny was alone in that old house still, 69 years after she had moved into it, moving around slowly with the aid of a walker in the wake of several frightening falls. She was barely able to cook anything for herself any more, and depended on the rather sad little offerings from Meals on Wheels. We spoke every day on the phone, and I lived in constant dread that something would happen to her down there.

Finally we talked about moving her into an assisted living facility, and to my surprise, she agreed. She didn’t have a huge amount of savings but we figured that selling her house would go a long way toward paying her rent for a while. She visited the veterans’ home in Winfield but found it too drafty and cavernous; at Ark City’s Presbyterian Manor she balked at having to use an elevator. Finally I took her to tour the senior living community in Winfield, where my mother lived. In addition to their nursing care units, they had two whole wings of assisted living apartments, and the price was as reasonable as it got.

In October 2019 we moved her in. It broke her heart that she had to leave behind many things she had lovingly cared for over the years — furniture that she had recovered and refinished herself, beautiful china, appliances, etc., but she wouldn’t have room in her new place, and she had already given me everything I wanted out of there. Our plan was to have an estate sale company come into the house before we sold it, and clean the place out.

And then came COVID-19. There were no estate sales, nor auctions. The house lingered on the market for months before finally selling for peanuts. The timing could not possibly have been worse. The things that had been left behind were just let go, because what else could we do?

For the next year I drove back and forth between Wichita and Winfield to take Genny to an ever-increasing number and variety of doctor appointments. This involved checking in and out of the senior community building, having my temperature checked, masking up, the whole bit. 100 miles of driving, sometimes twice that, if the doctor happened to be in Wichita. It was a lot, but I was happy to be able to see her in person, and she was forever giving me a blank check for my efforts, telling me to write it for whatever I needed to catch up my bills. And I cashed them, but never for what I really needed to catch up. I was too aware that she was running through her savings, and knew that her worst nightmare was to end up in one of the small double-occupancy rooms over on the other side of the building where my mother stayed.

And then on December 3, 2020, Jeanetta suddenly died. Genny was on the phone that morning, talking to my dad, Roger, when she saw on the caller ID that her daughter was calling. As they spoke numerous times by phone each day, Genny figured she would just call her back when she was done talking to my father. A few minutes later, one of the staff hurried into her room, put her in her transport chair and wheeled her all the way to the other end of the complex, where my mother was just breathing her last. Genny took her hand; later she told me it was still warm.

She would never forgive herself for not taking that call.

COVID wore on, and Genny grew depressed at her isolation. In addition, the lockdown rules meant she had a hard time getting her signature beehive hairdo fixed on a regular basis. After more than 50 years, she finally gave up the ghost and cut her hair, opting to wear it down with a headband from then on out. She hated it, even though I legitimately thought she looked cute like that, and people were forever telling her the same. “I hate to look in a mirror,” she said.

In the summer of 2021 I found myself burning up the highway taking her to appointments. There were eight in June alone, several of them in Wichita, requiring me to make double round trips on those days. After thinking about it a long time, I finally asked her what she would think about moving into my house in Wichita. Once again I was surprised when she agreed.

I spent several months making my rickety old 1930s house friendlier for walkers and wheelchairs. A friend lent me a 20-plus-foot aluminum wheelchair ramp, for which I built a custom side porch on my house. I completely remodeled the sole downstairs bedroom, which is just around the corner from the bathroom. I put up safety grab bars around the toilet and bathtub and added an extension with arms to the toilet seat. I customized a bathtub/shower seat so that it was tall enough to work with my giant antique cast iron tub.

Genny moved from Winfield to our house in Wichita in October 2021. Her decision to do so, I believe, came to bring her equal portions of comfort and regret. She missed her friends from the senior community. She was embarrassed by my dumpy old house. She didn’t like the way I cooked. But she was so happy to see her great-grandsons all the time, and they waited on her and hung out in her room watching TV with her a lot. She also came to be great friends with my cats, especially Miss Dusty Springfield. They developed a daily routine in which Dusty would wait patiently for Genny to finish her bowl of Cheerios, then lap up the milk.

Her moving in had mixed effects on me, too. I was gratified to be able to give back to this woman who had always been there for me, and I really dedicated myself to making her as comfortable as possible. But I was also dumbfounded when I realized just how debilitated she had become. It’s true that I had seen her frequently on my visits to take her to the doctor, but spending a couple hours with someone in public is vastly different from spending 24 hours a day with them at home.

I mean, I knew she was forgetful and often repeated herself — the usual signs of oncoming senility — but I was absolutely shocked when it became apparent that she didn’t always know who I was. We would just be talking and then she would say something that indicated she thought she was talking to a stranger, like referring to my son Nash not by name but as “my great-grandson.” Sometimes she thought I was my father, and she would tell me things about myself as though I were an absent third person and not the person right in front of her.

Other times I think she thought I was Troy, whose name she came to curse in her last days. One night I woke up to find her standing in her gown in the dining room, leaning on her walker in the dark of 3:00 a.m. She had shouted at me, and when I jolted awake and asked what she needed, she snapped bitterly, “Nothing. Just go back and wait for the next whore to come along.” I was baffled.

On St. Patrick’s Day of this year I wore a green t-shirt that I had never put on before. When I woke up Genny that morning, she did not recognize me, and when she asked, “Where’s Mike?” she wouldn’t believe that I was me. I called my sons in and she asked them, “Where’s your dad?” and they both immediately pointed at me.

“I don’t appreciate you pulling my leg like this, by God,” she grumbled. “It’s not very funny.” The same afternoon she told our neighbor, who often came to visit with her while I ran errands, that the three of us were pulling some sort of elaborate prank on her.

By dinnertime I thought the spell had passed, but then later that evening, as I brought her a snack in her room, she looked up at me and asked softly, “Whatever did happen to Michael Carmody?”

I pointed to my chest. “I am Michael Carmody,” I said. She frowned.

“No, I mean the boy. What happened to the little boy?”

“He grew up, Grandma,” I said quietly. “And now he is me.”

Genny took a minor spill one night — not a hard fall, but she slumped down on one of her ankles and injured herself. The doctor ordered physical therapy, and a woman started coming to the house twice a week to work with her. Genny was doing really well for a while, but one day, she just couldn’t get up and do it anymore. There was nothing obvious that predicated this; she just suddenly was unable to do much of anything. The tendons in three of the fingers in her left hand suddenly gave out, turning that paw into a perpetual finger gun, and she became terrified that the same would happen to her dominant right hand. Her misery grew in proportion to her dread, and she became meaner and more critical by the day, lashing out at me and others with uncharacteristic and entirely unnecessary cruelty.

“I’m living too long,” she said, every single day, to anybody and everybody she spoke to. “If you want my advice, don’t get old.”

Just three weeks before she passed, she entered a hospice care program, and we had all sorts of nurses and other support staff coming and going practically every day. When she heard the word “hospice,” she perked up — because she believed hospice workers were the people who came to “put you to sleep” when you were terminally ill, and that’s what she wanted more than anything. She had to be told repeatedly that this was not the case.

“Well, that’s the shits,” she’d reply.

Genny passed nearly two months ago now, and I have been trying to write this — or frankly anything — ever since. The passing of my mother figure, the family matriarch who all the living descendants of the Wyants (and Tallys too) still revere as the last living connection to our common past, hit me deeply from so many angles I have been unable to accomplish much at all. I have thrown myself into my kids’ projects and tilting at windmills. I am trying to get my shit together to lose this depression weight again. And I am struggling to keep up my end of the deal with my precious Honk subscribers, too — but as you know, I have been dropping the ball there. I thank you endlessly and sincerely for your patience with me.

In the end, Genny Tally was a lot of things to a lot of people. But to me, she was my personal savior and it is impossible for me to imagine what my life would have been like had she not been there to catch me on those countless occasions when I fell through the cracks. May she rest in well-earned peace, forever and ever, amen.