In the early years following its incorporation in 1870, Wichita developed in fits and spurts, growing quickly from a muddy cowtown into a beacon of proper civilization on the untamed plains. As the need arose for new buildings to house public offices, schools, civic organizations and the city’s wealthier private citizens, Wichita’s genteel nouveau turned up its collective nose at the simple wooden structures of the past and aspired to greater heights of architectural expression.

Perhaps no one (or in this case, two) made a more lasting impression on the landscape of Wichita than Willis T. Proudfoot and his partner George Washington Bird, of the firm Proudfoot & Bird. Between 1885 and 1891, these men designed some 70 buildings in and around Wichita, of which only nine remain today.

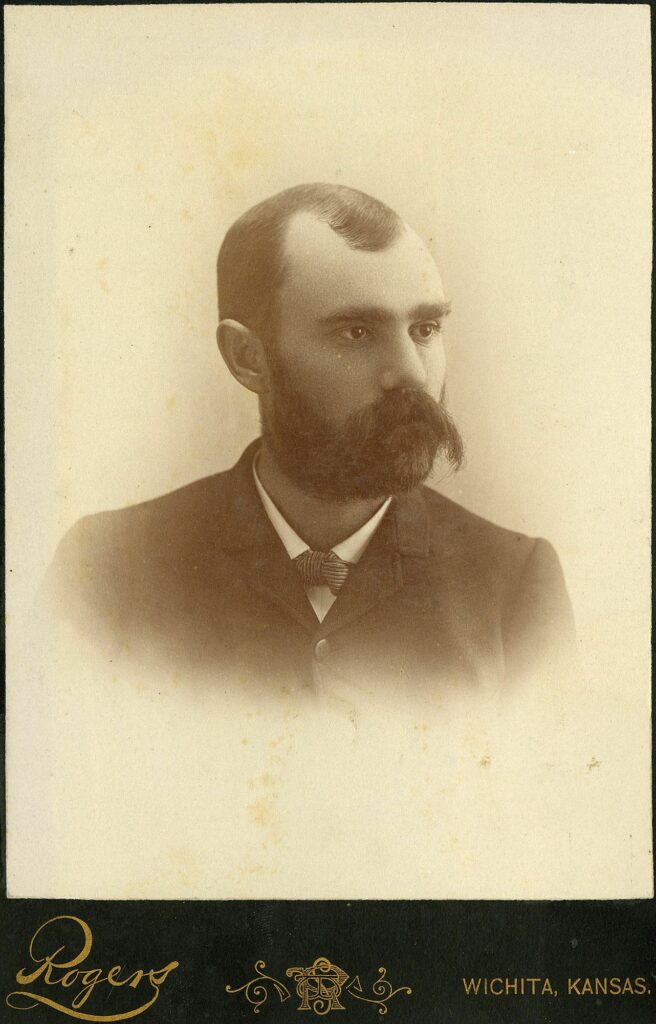

Proudfoot, an Iowa native, graduated high school in 1878 and by 1880 had secured a job with the famed Des Moines architects Foster & Liebbe. Not content with working for others, the young man struck out on his own, looking for design commissions in growing communities all over the Midwest. In 1884 he entered a course of study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT); though he only stayed in Boston a year, the effect on his design work was drastic. His earlier designs suffer by comparison to the far more elegant, mature works he would produce in the wake of his short formal tutelage.

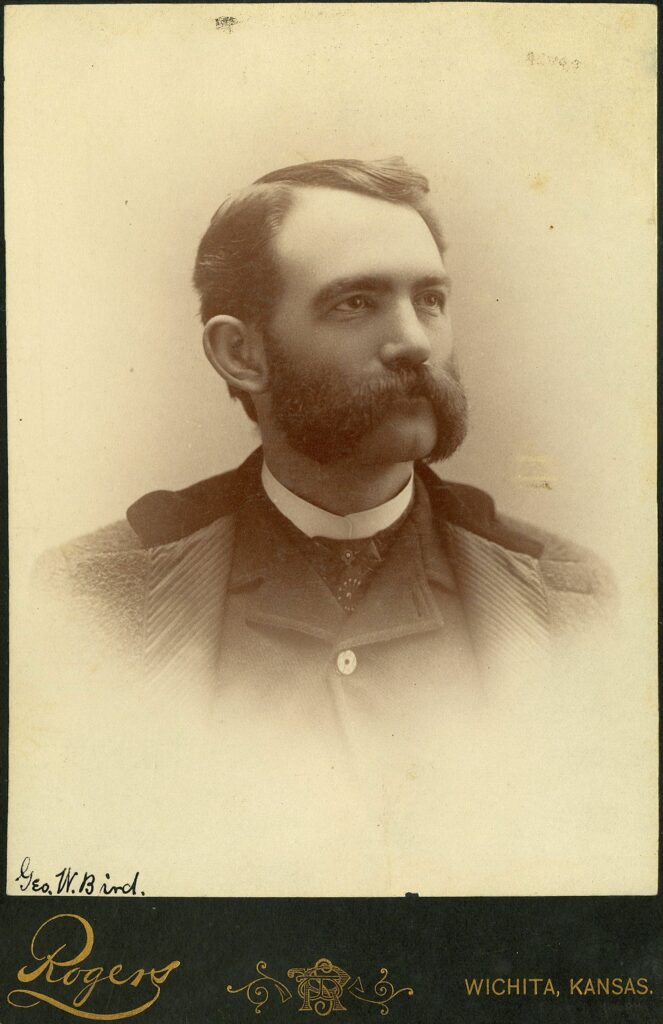

Bird was a few years older than Proudfoot, and hailed from New Jersey. Little is known about his early years, though he was rumored to have served as a woodworker in Philadelphia, where he may have also received some form of architectural training. Regardless of the provenance of his education, he was renowned for the beauty and elegance of his interior designs. In 1882 he found himself in Des Moines, also working for Foster & Liebbe, and it was most likely there that he and Proudfoot met, and the seeds for their partnership were planted.

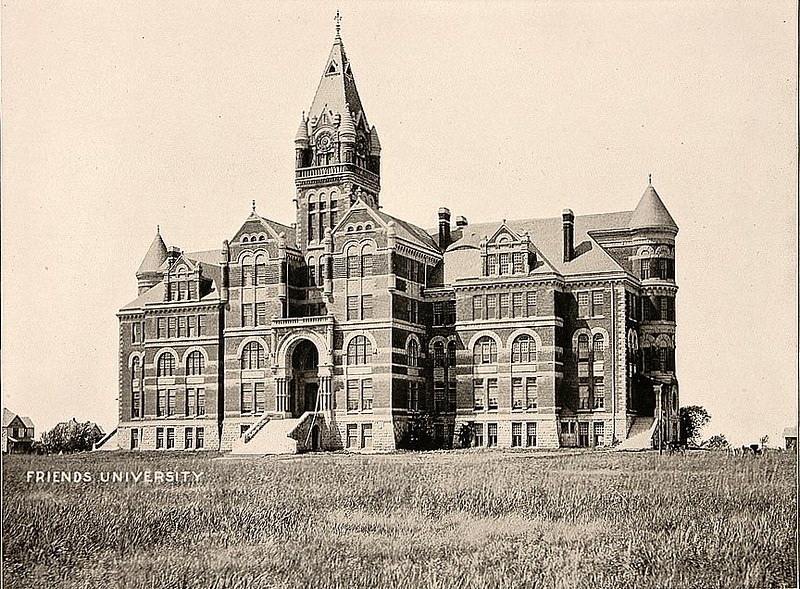

As a team, they quickly developed a modus operandus in which Proudfoot would set out by train to scour the prairie for work, and once commissions were secured, Bird would join him and do much of the actual design work. In 1885 Proudfoot landed a huge project in Wichita: the administration building for Garfield (now known as Friends) University. He set up office in town and was shortly thereafter joined by Bird.

Wichita was experiencing a huge building boom at the time; between 1880 and 1888 the city’s population doubled, then doubled again, then doubled again, swelling from 5,000 to 40,000. Everybody needed a place to live, or to do business, or to send their kids to school. An 1887 issue of the Wichita Eagle claimed that in that year alone, three thousand new buildings were erected in the city, including a mile of brick & stone commercial frontage. And Proudfoot & Bird arrived just in time to cash in.

Among their most notable projects: Lewis Academy in the 300 block of North Market, Franklin School in the 200 block of South Elizabeth, Park School at 1025 N. Main, the ornate YMCA building at First & Topeka (now known as the Scottish Rite Temple), the Wichita City Building (now home to the Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum), Riverside Cottage (electric streetcar kingpin Thomas Fitch’s private residence at 905 Spaulding, the first home in town to be wired for electricity), McCormick School on South Martinson, Fairmount Cottage (private residence of lumber magnate A.S. Parks at 1717 Fairmount) and Proudfoot’s own home, the beautiful Hillside Cottage at 303 Circle Drive, which later became the first clubhouse for Wichita Country Club’s golf course.

Proudfoot & Bird were famous not for the quantity of work they produced, but for the exceptional quality. They loved the native limestone quarried nearby in Silverdale and Winfield, and their idiosyncratic designs typically riffed on Richardson Romanesque and stylized Queen Anne elements, all the rage at the time. Considering the brevity of the period they spent working in Wichita, their body of work is staggering, averaging roughly one project per month.

And then came the bust. The real estate bubble popped, and the commissions slowed to a trickle, then stopped. In 1891, Proudfoot & Bird teamed up with architect Henry Monheim of Salt Lake City, submitting the winning entry in a contest to design that city’s City and County Building. The two pulled up stakes and left Wichita for good.

After a few years in the west, they wandered the country looking for work before ending up back where they had started, in Des Moines. Bird retired from the firm in 1912 and Proudfoot died in 1928, having turned out scores of designs for buildings in Iowa and surrounding states. Today there are 25 Proudfoot & Bird buildings standing in Des Moines alone, and 54 examples of their work nationwide are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Wichitarchaeology is a series of Wichita history columns originally posted in F5 Weekly. These articles are being presented here as they originally appeared, in some cases with additional photos, supporting links and/or addenda providing updated information. All photographs courtesy of the Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum. This post was first published 4/11/2013.