HOLY HOME VIDEO, BATMAN! Nearly a full year after this story was first published here at Honk, video from these gigs has suddenly surfaced on YouTube, posted by Kirk Rhorer, the drummer of Overhead Rejector. Your faithful narrator is truly shocked to learn this footage exists after 29 years! You will find it embedded in the story below.

Friday, June 17, 1994 was one hell of a day for sports fans. Arnold Palmer played his last-ever round at the US Open, the FIFA World Cup opened for the first time in the United States, the New York Rangers were fêted with a tickertape parade to celebrate their Stanley Cup win, the Rockets and Knicks faced off in game five of the NBA Finals and baseball’s Ken Griffey, Jr. tied one of Babe Ruth’s home run records.

But I wasn’t a sports fan then, and I can’t say I am one now. For me it was another workaday Friday in downtown Wichita at the ancient mom-n-pop sign shop where I worked. The place was one of a dying breed, the kind of shop that still produced giant advertising banners painted by hand in lead-based One Shot paint. It was enjoyable work on the whole, made more so due to the fact that my good friend David worked there, too. We carpooled most every day and spent our days together designing and producing all kinds of signage, chain smoking cigarettes and indulging in endless hilarious conversation that sometimes had us laughing so hard that the boss’ dour middle-aged daughter would come back from the front office to scowl and bark at us to keep it down.

On this particular Friday, Dave’s band Bottom Feeder and my band Sunshine Family and another band called Overhead Rejector were all set to play a two-night stand at the local heavy metal club, the Silver Bullet, which was located at the unlikely intersection of Maple and McComas, just a couple blocks east of West Street. This is a part of town most folks in Wichita rarely drive through, much less drive to — yet somehow the Bullet was consistently a great venue for us, and we always drew our biggest crowds there.

As the afternoon at work dragged by, Dave and I both grew more excited in anticipation of that night’s show, and our energy was running high. We were chattering away as we worked, listening as usual to the radio spewing the endless stream of “cutting edge rock” singles that had materialized in the wake of Nirvana, whose frontman Kurt Cobain had taken his own life only weeks before. Dave cracked wise about the songs we disdained, which were numerous and often in heavy rotation; we heard the current biggest hits thrice daily at work. Collective Soul’s “Shine,” that mumbly Crash Test Dummies hit, some Gin Blossoms thing, Green Day’s “Longview,” everything by Counting fucking Crows. At least it wasn’t the billionth repeat of “More Than a Feeling,” we shrugged.

Our boss, Don, entered the room in his stiff, arthritic gait. He was an old veteran of the Korean War and a former greaser who still loved to dance to the blues, and we were pretty sure he was having some boozy lunches and sleeping in his office a lot of afternoons. He treated us very kindly; I recall one day when he came up next to me and silently watched me using pencils and X-Acto knives, then complimented both my hands and my handiwork. Dave and I thought a lot of him.

“Hey, you boys hear about ol’ OJ Simpson?” Don asked as he sauntered in. “The police are after him, they say he killed his wife.”

Dave and I both dropped our jaws in shock. Neither of us were sportos but everybody in America knew OJ Simpson. And as far as I knew, everybody thought the world of him. I immediately rejected the notion out of hand.

“No way,” I said.

“I guess it happened last weekend,” Don continued. “You boys haven’t heard?”

We shook our heads. Neither of us consumed much in the way of TV or radio news at the time, and the story had somehow missed us. We discussed this seemingly preposterous turn of events for a minute, but lacking any additional context or information, eventually drifted back to talking about that evening’s upcoming show.

Later after dinner at home — the dilapidated Cenpeka Apartments — I walked upstairs to the second-floor unit where my pal Jeff, who was also Sunshine Family’s bass player, lived with his girlfriend. It was time. We hopped into his 1967 Dodge A100 van — painted in a lovely yellow and white two-tone scheme that once appeared to me as a lemon-flavored layer cake while I was on LSD — and drove down to our practice space to load up our equipment.

Just coincidentally, we practiced at another sign shop, where Jeff was then employed, and where I had worked the previous year. It bears mentioning that at the time, Wichita’s sign companies were staffed in large part by local musicians, as it was the kind of job where a person could exercise their creativity, and most of the shops were local family businesses with owners who were generally agreeable to the flexibility required to be a practicing musician. (Also, they wouldn’t test your piss!) And a major added bonus of being a “sign guy” was that it put professional design and production equipment right into your hands, giving you the power to create your own band merch — t-shirts, stickers, etc. — on demand, and far cheaper than paying to have it done. It was a good job to have.

Jeff and I let ourselves into the dark shop with his key, loaded up our gear and headed to the gig.

The bar called the Silver Bullet occupied a squat, unassuming , shoebox-shaped brick commercial structure that was built in 1967 — I think maybe as a fraternal order’s clubhouse — and as far as I could tell, it had never been upgraded. The place was about 2600 feet square in total and its only outward concession to ornamentation was a small vestibule that extended feebly out of the direct center of the front of the building, trimmed in limestone and fitted with an ugly steel fire door. As we pulled into the parking lot the sun was still up but there were already a lot of cars out front.

Inside the front door I immediately spied our drummer Moore and his identical twin brother John standing at the bar, both staring slack-jawed at the TV mounted up on the wall behind the cash register. On the screen, something like 20 cop cars were rolling down the highway very slowly behind a white Ford Bronco. The woman who ran the place — Maria, an immigrant with a thick accent, but from where, I have no idea — was behind the bar, also gaping at the tube.

“What the fuck is going on?” I asked Moore.

“Dude, see that Bronco? OJ Simpson is in there holding a gun to his head,” he replied with his typical molasses-thick slacker inflection. “I guess they’re tryin’ to arrest him for killin’ his wife or some shit. The whole thing’s fuckin’ berzerky.”

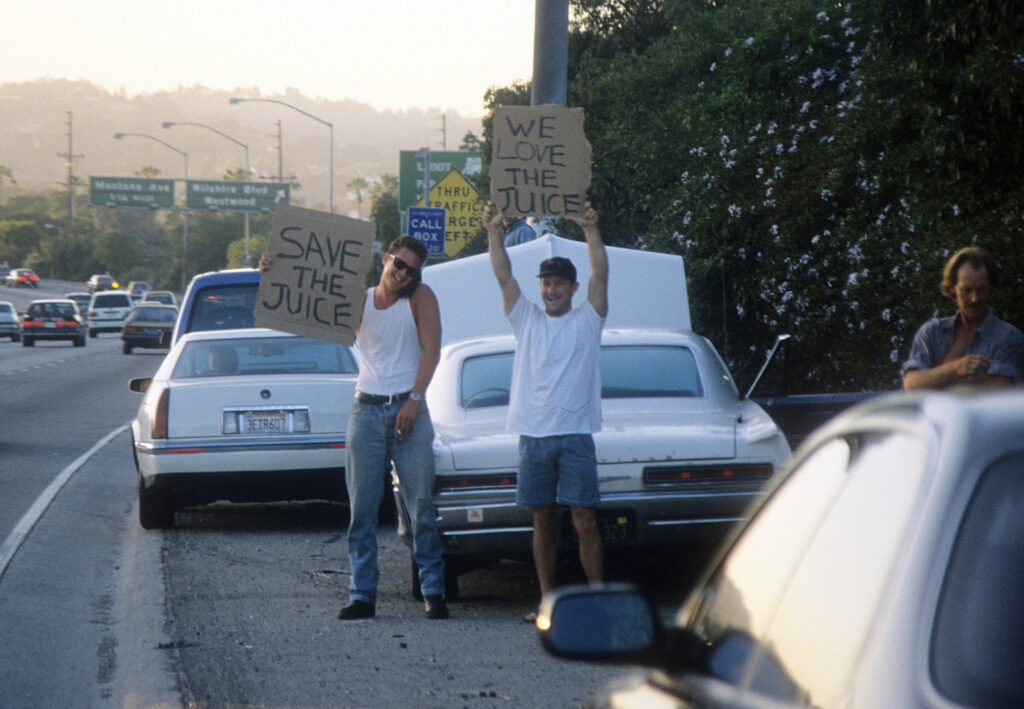

We watched for a while, noting in some of the news footage that the highway was lined with people cheering OJ on, holding up signs of support and applauding and pumping fists in the air as the Bronco leisurely rolled by.

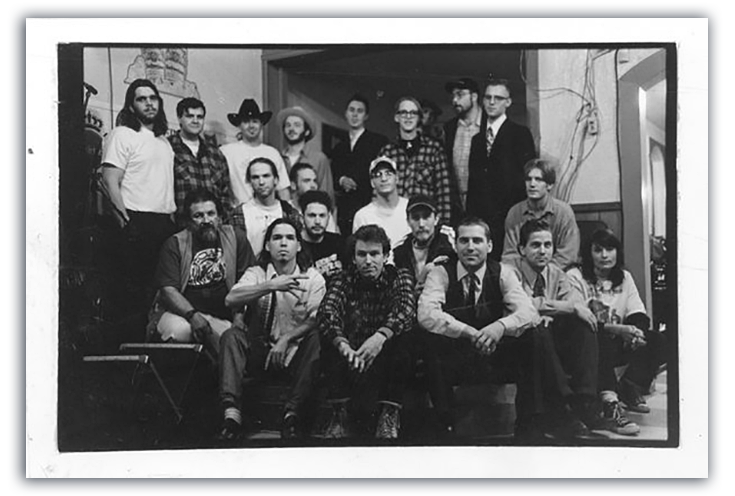

After a while I saw Dave and the guys from his band Bottom Feeder walk in. I didn’t know anything about the third band, really, or even how they ended up on the bill, but they showed up too. They were really sweet, a trio of younger guys more or less just out of high school, from Hutchinson up the road, and I think this might have been their first gig “in the city.”

The crowd started swelling. A healthy percentage of the regulars at the Silver Bullet (aka the Silver Toilet, aka the Silver Mullet, aka the Bullet) were various shades of hesher — the kind of (mostly) good-natured, party-hearty, beer-swilling rock & roll animals you might remember from “Heavy Metal Parking Lot,” but removed by about a decade. There was still plenty of love to be had for metal pioneers like Judas Priest and Iron Maiden, of course, but the younger guys — and they were mostly guys — were way into more modern acts like Pantera, Tool and even alt-rock-adjacent heavy hitters like Helmet, Alice in Chains and Stone Temple Pilots.

My band played hard rock, but of a weirdo version of it that Jeff had described as “heavy without the metal.” He wasn’t wrong. I was always surprised at how well our oddball material went down with the Bullet people, whom my own ridiculous prejudice had led me to assume might not be that open-minded about music. We shared the bill there several times with other popular locals and those riff-hungry animals always made us feel like proper rock stars. I was humbled and grateful for their endless enthusiasm for what we were doing.

On this particular Friday the house was pretty well-behaved, but as the night progressed and the room filled with more people, and drunker ones at that, it started to feel a little rowdier. Things were warming up when the Overhead Rejector kids took the stage. They played a very tight, angular, noisy, aggressive set and got a vigorous response. I felt like this was going to be a good night.

Bottom Feeder went up next, running through their set of Dave’s heavy, funny, memorable tunes to even greater response from the crowd. A really shit-hot shredder who grew up on ’80s thrash like Megadeth and Anthrax, Dave had remarkably broad tastes and a sharp ear for melody and — though he might roll his eyes to hear me say it — hooks. His lyrics were often brutally funny but sharply pointed, too; he lampooned his own southside Wichita white trash upbringing while also taking a perverse pride in it, and when he wrote about interpersonal issues, he could be as simultaneously hilarious and blackly bitter as prime-era Elvis Costello or Joe Jackson. We all knew the words to his best tunes because they were catchy as hell — and the rest of the band rocked, too.

And then it was our turn. The Sunshine Family included me and my friend Tom (aka the Blind Reverend) on guitars, Jeff on bass and Moore on drums. We hopped in with both feet and got people jumping around pretty good that night. I think this show might have been the first time Jeff and I kissed one another on the mouth while in the middle of a song — a shtick we adopted for a time as part of our stage antics, just to rankle any potential homophobes in the house. I have a vivid memory of Jeff’s old 1980s-era Pac-Man collectible drinking glass from Arby’s, filled with water at his foot next to his various noise pedals. And I remember it being quite hot and, as always, extremely loud. We ran through one rocker after another, riding the waves of joyous energy being beamed back at us from the smiling, head-banging denizens of the pit in front of the stage. And then we were at the end of our set, and there was much cheering and sweating and my ears were ringing to beat the band. It had been a good show, but we all knew from prior experience at the Bullet that the Saturday night show would be bigger — it always was.

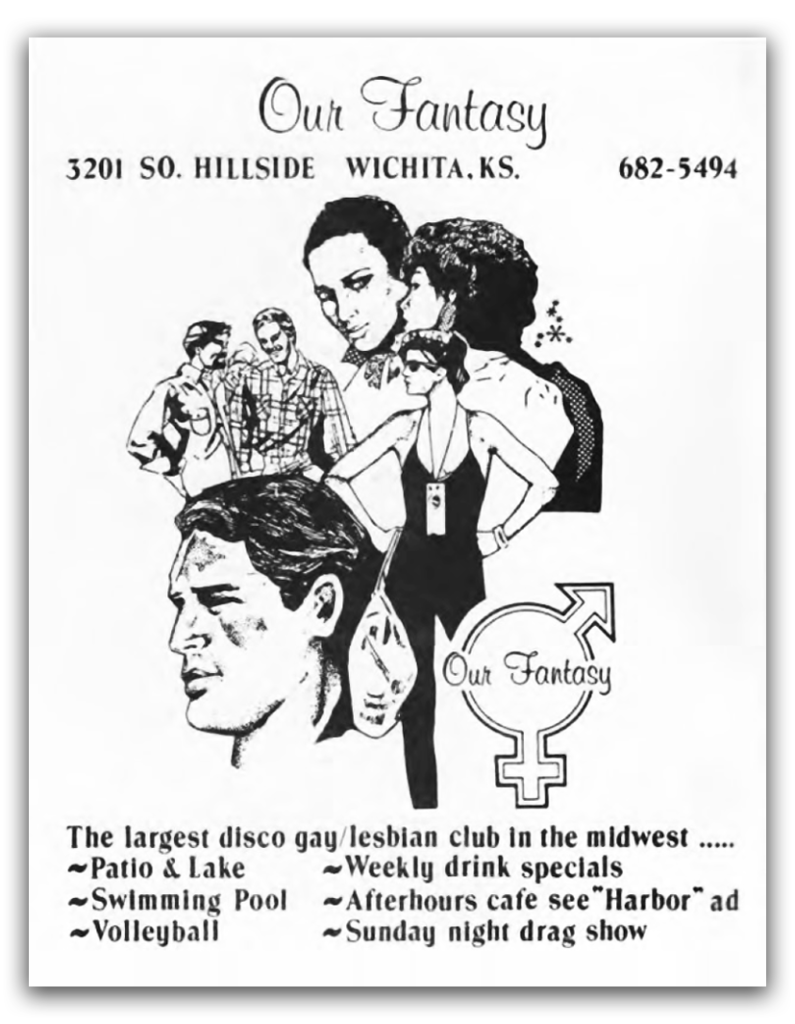

After we had put our gear away, we asked the kids from Hutch if they wanted to join us for breakfast. It was just about 2:00 a.m. by this point and there weren’t very many options open, but we knew just the place. We headed down south to 31st South & Hillside, the location of Wichita’s most storied gay bar, Our Fantasy. It wasn’t just a bar, it was a complex — made up of a discotheque, a separate country-western bar, an outdoor pool and volleyball court, and a kickass diner called the Harbor, which was only open at night.

We walked into the Harbor in time to get seated at a long table just before the door from the adjacent disco opened wide and a considerable stream of drunken, sweaty, mostly gay patrons flooded noisily into the room. A few randos asked if they could join us in the two or three empty chairs at the end of our table and of course we invited them to sit. Soon the whole diner was engulfed in inebriated cacophony and a thick haze of cigarette smoke. The Overhead Rejector guys, one of whom was celebrating his 21st birthday that weekend, seemed extremely jazzed at everything that was going on.

In the conversation that followed, OJ Simpson came up again, and everyone shook their heads, except for one of the drunken randos.

“Nah, uh-uh,” he said, shaking his head side to side. “That motherfucker did that shit.” Our group lapsed for a moment into awkward shrugs and chuckles and then the waiter arrived to save the day.

The Harbor was famous for its omelettes and had several named for famous local drag queens; there was the Tish, the Rusty, the Whumbly (I think?) and of course, the Fritz, named after the legendary Fritz Capone, who had once been crowned Miss Gay Oklahoma 1981. I ordered an omelette with ham and cheese and when it came I was so famished I devoured it in no time at all, with hash browns, toast and coffee too. An immensely satisfying close to a fine night.

I don’t recall now if we started talking about the jerseys that night, or if it came up the next morning. I don’t recall even whose idea it was, mine or Jeff’s. But clearly we both thought it was worth acting on, and if we were gonna do this thing, we’d have to act fast.

Early (well, not too early) the following day, Jeff and I got in his van and drove down to the sign shop where he worked. Our plan was to screen-print a one-off set of four matching t-shirts, patterned after the football jersey OJ Simpson wore during his glory days as a running back for the Buffalo Bills — and the Sunshine Family was going to wear them onstage that night. People were so hyped about the OJ situation, we just knew they would shit.

As neither of us were super into football, we called a friend for reference to double-check whether we had the right jersey number and team colors. Jeff laid out the design on the computer, burned the screens and set up the printing workstation. As I had on earlier occasions, I served as his printer’s monkey, providing assistance during the production process. Before long we had four white t-shirts, each with a big 32 in red and blue on the front and black block lettering across the back shoulders reading SIMPSON.

We had, of course, talked to both Tom and Moore ahead of this to make sure they were OK with the idea, and having agreed, we swore them to secrecy. Nobody outside the band, with the exception of our domestic partners, knew what we were up to.

That night we showed up in our regular street clothes, which is what we most generally performed in back in those grungy anti-glam days; our custom shirts remained hidden in the van through the first two bands’ sets. And we had indeed been correct in our forecast for a bigger crowd the second night, too. By halfway through the proceedings it was clear that this was the wildest house I personally had ever seen at the Silver Bullet. Now I was starting to get apprehensive. What if we mounted the stage in the OJ shirts and got booed? Only time would tell.

The Overhead Rejector kids played another sharp, roaring set and were treated to a raucous reaction from the crowd, getting more amped as the evening wore on. Then Bottom Feeder uncorked their shit and the vibe in the room immediately jumped three levels. Superheated metal kids jumped around and hooted like apes, caroming off one another in the crowd as Dave and his crew ran through one grimy slab of rock after another. The air thickened, every breath seemed to be drawn through a hot wet sponge floating in a dirty ashtray.

It almost felt dangerous.

Finally Bottom Feeder’s set was over and those guys, absolutely soaked to the skin in sweat, moved their gear offstage to make room for ours. Jeff’s van with all our equipment was parked directly outside the north doors adjacent to the stage, and in short time we loaded in and got everything set up, turned on our amps and tuned our guitars. The audience was yelling at us now to hurry up and play, but we had one more quick preparation to make.

The four of us — Jeff, Moore, Tom and me — adjourned quickly to the van for one last chance to have a quick toke of reefer — and to change into our OJ Simpson jerseys.

“All right, let’s do this shit,” said Moore. We took a breath, opened the stage door and ran inside.

In the thirty-plus years I have played live music, I cannot recall a single moment that was more purely, overwhelmingly rock & roll than this one. When the drunken metal maniacs in that bar that night caught a glimpse of us in our matching number 32 jerseys, they simply lost their fucking minds. Devil horns were thrown all over, hands were cupped around mouths to amplify screams of FUUUUCK YEEEEAAAAAAH!!!, the deafening applause and hoots of laughter creating a palpable sensation of force, the crowd’s energy literally pushing back at us onstage before we had played a single note. Jeff and I caught eyes as we strapped on our axes, both of us a little dazed in the furious sustained blast of raw power coming at us from the room. Moore counted off four and we launched our offensive.

Everyone on the floor jerked into action on the count of four, as though a giant lever had been pulled. A few rowdies literally swung from the rafters halfway back across the room near the sound guy, who was trying his best to protect his mountain of gear from being bumped, tromped on and spilled into by the wild jackals standing, jumping and even dancing on adjacent tables. We played and played and played — until Maria yelled at us to stop, and then we played a little more and by the end people started dropping, with a few rowdy hangers-on continuing to bellow for yet more, even as we began unplugging our gear. Now we were just as wet as everybody else in the room, sweat dripping down our noses and running in rivulets off our guitars. I, for one, was completely exhausted — and beatifically satisfied.

Over the many years that have passed since that night, this t-shirt shenanigan of ours has come to needle me, and I have to say that if I were then the person I am now, I would not have done it. I was 25 years old and more than a little obnoxious at times; I enjoyed being a little provocative, I think, and didn’t really give a shit what people thought as long as we gave them something to talk about.

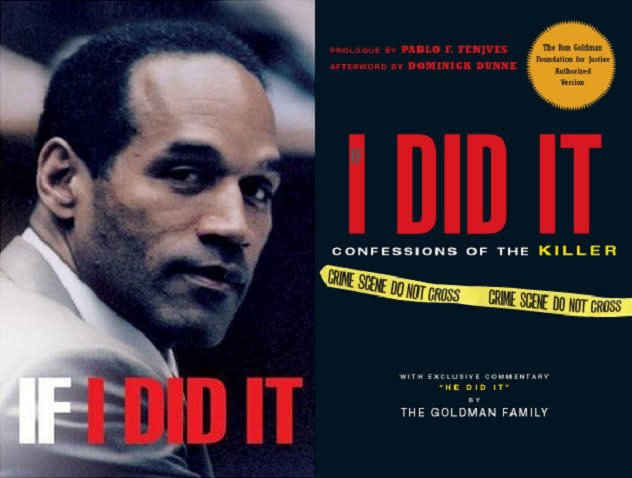

And I swear, it honestly didn’t really occur to me that OJ Simpson was probably really guilty until much later, when he was found culpable for the deaths of Nicole Brown and the extremely unfortunate Ron Goldman in the civil trial that followed his murder trial. Later still, when I heard of his plan to release a book called “If I Did It (Here’s How It Happened),” I felt positively sick. This shit was nothing to cheerlead.

The younger me had not for a moment considered how it might feel for the Juice’s kids to see dorks like me rooting for the man whose out-of-control toxic masculinity had taken away their mother forever. I wasn’t even a football fan. I was just in it for the lulz — and we scored lulz a-plenty. I wonder how many of the people in the crowd there that night would still find it funny or cool today. On the other hand, how many even remember it?

So I suppose it doesn’t matter. What I will always carry with me from the experience is that what felt like my greatest moment as a performing musician will be forever attached to this rather obtuse, slightly embarrassing act of buffoonery. But at least I can take some value from it by using it as a mile marker for how I have become a more sensitive person, in at least this one little way.

It ain’t much, I reckon, but I’ll take it.