When driving along on the commercial streets of central Wichita, one occasionally notices a well-preserved vintage home or two wedged incongruously between, say, a Popeye’s Chicken and a Sonic Drive-In. In the middle of mile after mile of business development, there remain like stubborn sentinels a number of residential dwellings that have stood since the early days of the city, when locales such as those known today as Midtown were far-flung suburbs.

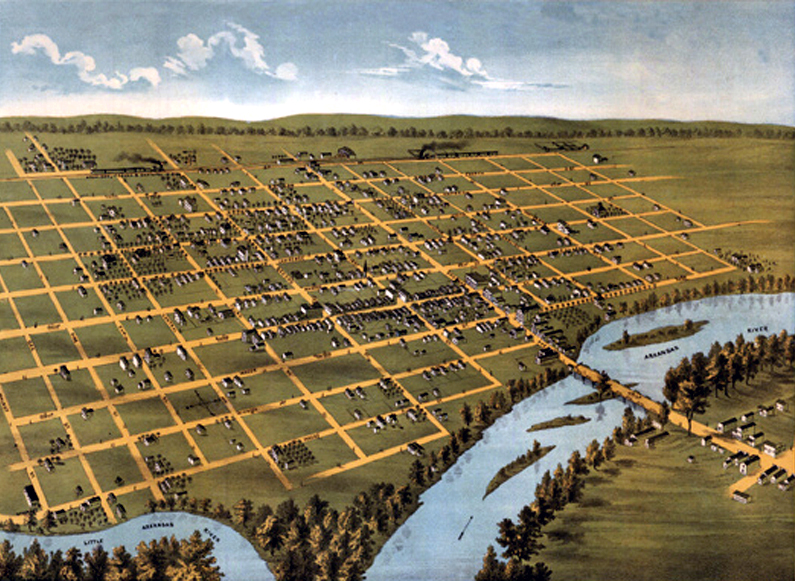

Back in 1870, when the city of Wichita was officially incorporated, there was not much at all in the way of infrastructure. In fact, most of what was to become the city proper existed only in the minds of visionary plainsmen like James R. Mead, William “Dutch Bill” Greiffenstein and D.S. Munger, all of whom claimed land in the area before the city charter was signed.

Mead selected what would become prime territory, from present-day Washington to Broadway on the east and west and between Central and Douglas on the north and south. Greiffenstein snatched up land on the south side of Douglas east of the river and later became known as the “Father of Wichita” for giving away much of this property to entrepreneurs who would develop it for commercial use.

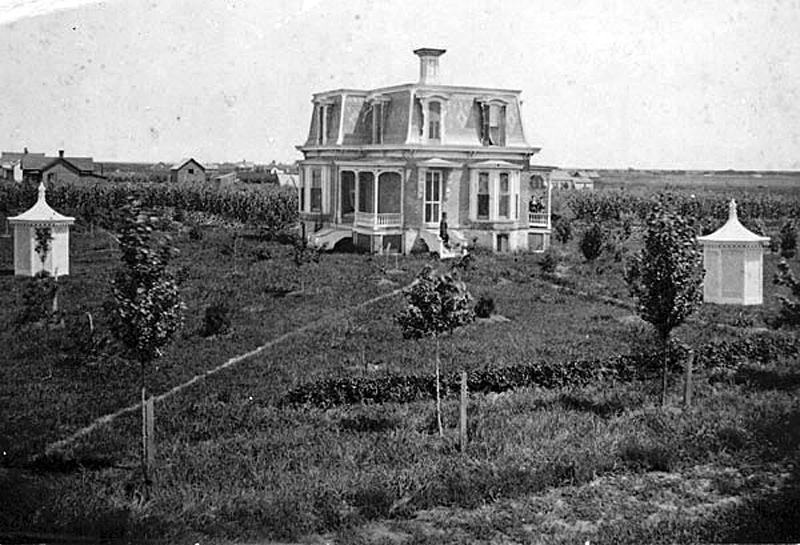

But it was Munger who made the first real improvements, building his rustic house by hand from local materials all the way back in 1868. This house, which served as the town’s first hotel, church and post office as well as Munger’s personal residence, stood near Ninth & Waco— and still exists , thanks to a bizarre feat of preservation. The Munger House was purchased in the 1870s by Wichita’s first banker, W.C. Woodman, who then actually built his beautiful Victorian house, Lakeside Mansion, around it. Decades later, the newer construction was razed, revealing the original cabin within. It can be seen today at Wichita’s Old Cowtown Museum. (The administration building at Cowtown, by the way, is modeled after Lakeside Mansion.)

Mead was a man of considerable wealth, having established a lucrative trading business among the natives and early white settlers of the plains as far back as 1859. The house he erected at 307 E. Central (current site of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception) was a fine, large brick structure with a stylish mansard roof.

Wichita Board of Trade’s first vice-president, J.C. Fraker, shortly thereafter built a lovely Second Empire home just across the street at 306 E. Central; this is believed to be the first house in Wichita designed by noted architect William Sternberg, who brought European aesthetic sensibilities back with him after visiting the 1855 World’s Fair in Paris.

Greiffenstein’s first home was, like Mead’s, a proper grand manse befitting a city father. Located just south of Douglas on Water Street, the two-story house with full-width front porch supported by six stately columns stood from 1871 to 1910, when it was moved to make way for the construction of the Forum. (Read more about that here.)

All these houses, save Munger’s, now enshrined in a museum, are long gone, consumed by the growing thrum of commerce in Wichita’s heart. But others held on longer.

Maurice Levy was president of Wichita National Bank when he hired Sternberg to build his mansion at the northeast corner of First & Topeka in 1887. Fifty years later, when the house was demolished, it was the last remaining residential structure in the neighborhood, completely surrounded by commercial buildings. (Perhaps fittingly, at that time it served as headquarters for the predecessor to the Chamber of Commerce.)

In the 1880s, Lawrence (Broadway) north of Murdock was known as “Lumberman’s Row” for the series of houses built there by men who made their fortunes providing building materials for the young city. One such fellow was Mark J. Oliver, who had a Sternberg-designed house at 1105 N. Lawrence (Broadway) that survived for many decades before being razed; the lot was rezoned “light commercial” and today the Saigon restaurant stands in its spot.

J. Hudson McKnight owned most all the land bordered by Douglas, Kellogg, Hydraulic and Grove, and operated a farm on much of it well into the 20th century. He fought against the encroachment of city development and improvement all his life, refusing even to allow electrical service to run to his property. When he died in 1925, his idyllic mansion, Willowdale, was still lighted by gas. The house stood until 1969, when it was razed and replaced by a generic commercial building. Willowdale is so ephemeral that it is hard to even find a photograph of it today.

Wichita Eagle founder Marshall Murdock built his house in the boondocks on North St. Francis in 1874, where it stood until being moved to Cowtown in 1982. The cross street where the house stood still bears the name Murdock.

And then there are the survivors, now seemingly so out of place.

The Hypatia House at 1215 N. Broadway is a gorgeous execution of the Dutch Colonial Revival style, built in 1906 for the manager of a local coal company. It was purchased by the Hypatia Club, a “women’s self-improvement organization” in 1934 and is now protected under the auspices of the National Register of Historic Places. Its neighboring buildings include several fast-food restaurants and a brutally austere motel.

Likewise, the former home of Judge Sankey at Broadway and Elm now lives on as the 20th Century Club. Like the Hypatia House, this paragon of late 19th century elegance was saved by virtue of being purchased by a civic organization in 1923. The Sankey House was updated considerably in the 1931 with the addition of the Louise Murdock Theater, added to the home’s rear along its Elm Street frontage. It now shares the block with the Lord’s Diner.

One cannot help but muse at what Mead, or Munger, or Greiffenstein might think of the ungainly, bloated sprawl of Wichita as it exists today. Greiffenstein’s first trading post was miles from town, at the present site of Eberly Farms— which is now well within city limits. Considering that the original township of Wichita did not even cover what we think of as “downtown” today, it is perhaps fitting that these men all built their original domiciles on what were then the outskirts of town, just as the well-to-do continue to do in the modern day. How could they have known that those edges would so quickly become the center?

Wichitarchaeology is a series of Wichita history columns originally posted in F5 Weekly. These articles are being presented here as they originally appeared, in some cases with additional photos, supporting links and/or addenda providing updated information. All photographs courtesy of the Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum. This post was first published 4/18/2013.