“Power pop is what we play,” said Pete Townshend in 1967, referring to his band the Who, upon the release of “Pictures of Lily,” their cheeky and adolescent ode to masturbation. He was not wrong, entirely — the Who absolutely trucked in super catchy pop tunes delivered with, well, power — but the term “power pop” as we use it today has come to mean something more specific.

But what exactly? Like obscenity, it’s hard to define, but you know it immediately when you hear it — raggedy/jangly guitars, creamy vocal harmonies, hooks for days, lyrics about your best girl (because power pop is almost entirely made by dudes) and what you, and maybe the kids, are gonna do together tonight… You know, power pop.

Looking back on the popular music of the post-British Invasion ’60s from the modern day, one can be forgiven for finding even the heaviest acts of that era charmingly inoffensive to the point of twee; nothing in the catalogs of the Who or the Stones or the Beatles sounds particularly heavy in a post-Pantera environment. It’s hard for the kids of today to appreciate the true impact of the Beatles — because they have been soaking in the band’s ubiquitous influence their whole lives. A fish doesn’t know it’s wet, after all.

Ever see a YouTube video in which a colorblind person puts on a pair of EnChroma glasses and sees color for the first time and promptly loses their shit? The whole of America collectively did that on February 9, 1964, when the Fabs appeared for the first time on Ed Sullivan’s show. It was as if the music on the radio had been in black-and-white the whole time and nobody realized it until the moment the band hit the stage and ripped into a smoking run through “All My Loving.” The door was kicked opened and suddenly we weren’t in sleepy, sepiatone Kansas any more. The Beatles were Technicolor, Cinemascope, in 3D.

That was the Power Pop Big Bang — the night the Beatles broke into the households of 73 million Americans, immediately rendering quaint and flaccid the pop radio offerings to which they had been acclimated. Stale and corny acts such as Mitch Miller, Perry Como, Pat Boone, Percy Faith and Anita Bryant were instantly relegated to the squarest corner of Squaresville.

This was pop music in America before the Beatles. Mitch Miller, a Columbia Records A&R man who had passed on signing both Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly, hated rock & roll and did everything he could to stop it from spreading. His weekly “Sing Along with Mitch” show ran for three years — until the Beatles hit and the public quit watching.

The next day, every single teenage boy in the viewing audience started combing his bangs down over his forehead, and a sizable coterie thereof raided local pawn shops coast to coast, trading socked-away wads of paper route money for cheap electric guitars. By springtime, wobbly, gritty jangle burst from countless American garages like flowers erupting from soil. “The local rock group down the street is trying hard to learn their song,” Micky Dolenz would sing not long thereafter in the Monkees’ suburban ode “Pleasant Valley Sunday,” illustrating how commonplace the American garage band had become in the aftermath of the Beatles.

But it wasn’t just the kids who were transformed. A whole generation of working musicians, from the Beach Boys to Bob Dylan to an endless of list of then-nobodies who would go on to later fame, were profoundly influenced by the Beatles. Earnest folkies, country pickers, rhythm & bluesmen, even long-in-the-tooth balladeers — all fell into a Liverpudlian swoon. Dylan introduced the Beatles to reefer on their first meeting and before you know it, he’d gone electric and was writing pop hits for Manfred Mann, the Turtles and most notably, the Byrds.

And speaking of Beatle-struck folkies, the Byrds —fronted by bluegrass-friendly coffeehouse picker Roger McGuinn, whose mind was blown when he heard George Harrison’s 12-string guitar on “A Hard Day’s Night” — certainly hold a valid claim to being power pop pioneers, with tracks like “I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better” and “All I Really Want to Do” laying down the fundamentals of the form without even trying.

And the same can be said of any number of British Invasion acts, including the aforementioned Who, the Kinks, Dave Clark Five, the Animals, certainly the Troggs. The ingredients were all being mixed together, but the cake wasn’t in the oven yet.

No, we are still not really quite in truly proper power pop territory until we get over the Peak ’60s hump, when the music got heavier and the artists became more self-serious and rock & roll was for the first time considered worthy of legitimate criticism. Power pop came on almost as a reaction to that vibe, a return to simpler times, a callback to an age that already seemed long ago, before Vietnam heated up and our civil leaders were being assassinated in bulk. What was it Ferlinghetti said? “Fuck art, let’s dance!”

Enter Badfinger, née the Iveys. Discovered and championed by Beatles henchman Mal Evans, the band was signed to the Fabs’ brand-new startup record label in 1968. Apple Corps boss Neil Aspinall changed their name and Paul McCartney wrote and produced their first hit, insisting they record their version exactly as it appeared on the demo he had made.

Of course Paul was right. “Come and Get It,” a bouncy come-on to the greedy tied thematically to the film The Magic Christian, for which it was written, did indeed make the Top Ten on both sides of the pond, but it was not Badfinger’s seminal contribution to power pop. That honor goes to their next three singles in a row — “No Matter What” (1970), “Day After Day” (1971) and “Baby Blue” (1972). All three are love songs comprised of immaculate series of irresistible hooks, and all feature yearning, aching vocals and lush, velvety cushions of three- and four-part harmonies. If that ain’t power pop, I’ll kiss your ass.

From there on, the form began to take shape and propagate, as a whole new generation of younger musicians forged its own interpretation of their seminal influences from the ’60s, just as those earlier bands had aped and transformed American R&B, fusing it with English music hall, rockabilly, blues and doo-wop stylings. All over America, the kids raised on the Beatles were ready to take their own stab at it.

Suddenly there’s Todd Rundgren, who recorded his landmark Something/Anything double album almost entirely by himself, some of it in his own home, laying down track after track, switching from one instrument to another — just as proto-power-popster Emitt Rhodes had done the year before on his vaunted eponymous debut album. (There’s a whole other bedroom recording story out there waiting to be written.) Rundgren’s influence on future generations of musicians is inestimable, and he is still working today, in his 70s. Rhodes had bad luck in the music industry and dropped out of the spotlight for years but made a surprising comeback in the 2010s with his Rainbow Ends album, featuring a huge list of top-shelf guest musicians.

Out of Cleveland came the clean-shaven, matching-suited Raspberries, who stood out from the era’s cosmic beardos and Rapunzel-locked hobbit rockers by spitting out a series of four gold-standard power pop singles in the short span of two years — “Go All the Way” and “I Wanna Be With You” (1972), and “Let’s Pretend” and “Tonight” (1973).

California’s Flamin’ Groovies, a band that had long been tagged as Rolling Stones wannabes, already had three largely unsuccessful albums under their belt when they replaced their existing frontman with a teenager, put on Mod suits and recorded the ageless “Shake Some Action,” setting them on an entirely different vector.

Big Star emerged from Memphis as power pop’s own Velvet Underground, a band whose records proved massively influential despite the fact that almost nobody bought them. The band started as a partnership between local garage band stalwart Chris Bell and former teen heartthrob Alex Chilton, who had found chart success — seven Top 40 singles, including a number one and a number two — with his early band the Box Tops. Together they wrote a handful of enduring classics, including “When My Baby’s Beside Me,” the absolutely gorgeous ode to puberty “Thirteen” and the ebullient “In the Street,” which most folks know chiefly as the theme song from That ’70s Show. Bell joined the 27 Club when he crashed his Triumph automobile into a light pole, and Chilton went on to become a revered grand old man of American music, enjoying greater exposure later in his life. He died of cardiac arrest in 2010.

Down from Illinois came a ragtag foursome who would go on to become the biggest-selling power pop act of all time, Cheap Trick. A band with great visual appeal, exhilarating stagecraft and chops chops chops, they had a hard time getting a foothold in America’s ears until, ironically, they recorded a live album in Japan, where they were inordinately and inexplicably huge. Live at Budokan — which was just this year selected for preservation in the Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry for its cultural significance — sold three million copies and sent the single of the live version of “I Want You to Want Me” (an infinite improvement over the sterile studio recording) to number four on the Billboard Hot 100. The band would go on to enjoy a remarkable second act a decade later, when they scored their first number one with their 1988 power ballad “The Flame.” In 2009 they worked up a version of the entire Sgt. Pepper album, with numerous guests and a full orchestra, and released a concert film and live album of the results, demonstrating their debt to the Beatles. Cheap Trick is still a ferocious touring act today, as they enter their sixth decade together.

Okies Dwight Twilley and Phil Seymour launched themselves into the Top 20 with “I’m On Fire,” a song they recorded with little oversight or outside contributions in a Tulsa studio. Their debut album Sincerely is now power pop canon but at the time barely made a squeak. The two parted ways and each landed a later solo hit — Twilley with “Girls” and Seymour with “Precious to Me,” both in the early 1980s. Seymour, who can also be heard singing backup on the Tom Petty singles “American Girl” and “Breakdown,” sadly succumbed to lymphoma at age 41 in 1993.

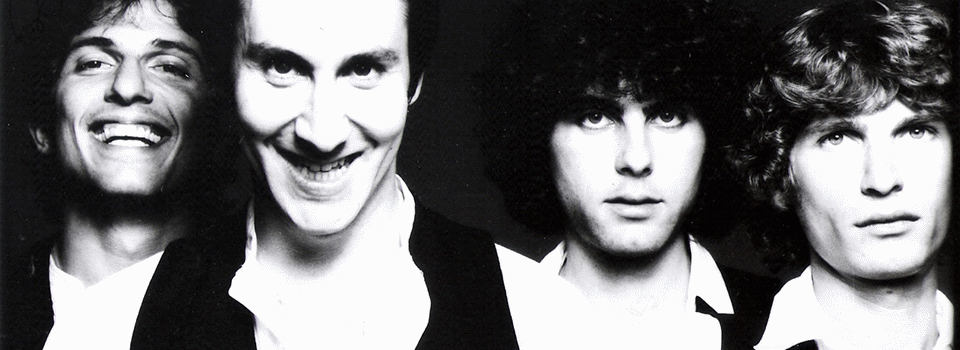

As disco and punk rock held down opposite ends of the listening public’s attention, the Knack dropped “My Sharona” like a bomb and for a brief moment in time there, it seemed like the only record in existence, becoming so ubiquitous that it sparked a backlash. The band’s landmark Get the Knack album remains perhaps the definitive document on the psyche of the horny teenage boy. (Leader Doug Feiger passed in 2010, felled by lung cancer.)

These guys had the fastest-earned gold single on Capitol Records since the Beatles’ “I Wanna Hold Your Hand.”

And the list goes on and on, from sea to shining sea — but as it does so, most casual music listeners will grow less and less familiar with the names. Despite power pop’s sterling provenance (not to mention its infectious nature), somehow the form has never received the mainstream acceptance it deserves. There are a few one-hit wonders, fewer two-hitters, and a remarkable pile of talented, ambitious, exciting no-hitters, bands that made great records and almost certainly had fevered fan bases, but never charted. The Nerves, the Records, the Other Ones, Greg Kihn Band, Tommy Keene, the Paul Collins Beat, the Nick Lowe/Dave Edmunds/Rockpile contingent, the dB’s, the Romantics. Later on there are the Bangles (a comparatively rare female presence in the genre), the Church, the Three O’Clock, Marshall Crenshaw, a sizable portion of the late XTC catalog, the Primitives, the Posies, Redd Kross, Jellyfish, Teenage Fanclub, Matthew Sweet, Superdrag, Fountains of Wayne and on up to the modern day, with youngsters like the Lemon Twigs carrying on the flame.

Though the form has been frequently dismissed and scorned for a half-century, power pop isn’t going anywhere. It has spent the past 50 years bouncing back and forth across the Atlantic, turning on one generation after another with its joyfully melancholic guitars, its cotton candy clouds of dreamy vocals, its ceaseless teenage yearning, its almost mathematically economical structure and its sheer capacity for instant nostalgia. And who isn’t a sucker for that?