Author’s Note: This is the first installment of New Old Stock Cinema, an ongoing series of reviews of films and television shows that I am viewing in the modern day for the first time, despite the fact that they were released many years before. Yes, they’re old — but new to me. Consider this a sub-department of Eyelands in the Stream.

How did this happen? I mean, I know it was 1968 and there was a lot going on — but what do you suppose it was that inspired Otto Preminger to try to cram every bit of it into one zany experimental swinging sixties free love mobster hippie LSD sex comedy? How did he manage to cast Groucho Marx, Jackie Gleason, Carol Channing, Mickey Rooney, Cesar Romero, Frankie Avalon, Arnold Stang, Peter Lawford, Burgess Meredith, Michael Constantine, Austin Pendleton, John Phillip Law, George Raft, Frank Gorshin, Alexandra Hay, Richard “Jaws” Kiel, Slim Pickens, Harry Nilsson and ’60s proto-supermodel Luna, all in the same film? And how was Paramount talked into going along with this insanity?

To be sure, it was a time of change on an epic scale, and the tumult and uncertainty of the era were mirrored perhaps a little too harshly in Preminger’s contemporary career. The man who had challenged convention, courted controversy and electrified audiences for decades with edgy dramas such as Laura, The Man with the Golden Arm, Anatomy of a Murder and Advise and Consent seemed to have lost his way in the all-engulfing cultural maelstrom of the ’60s, and one can be forgiven for suggesting that he may have found himself grasping at straws, artistically speaking. The bloom was off his rose.

Preminger’s last well-received film, the 1965 naval epic In Harm’s Way, marked the end of an era in many ways. The straightforward World War II film featured John Wayne, Kirk Douglas, Patricia Neal, Henry Fonda and other heavy hitters from the Golden Age of Cinema — then already in full decline — and was among the last black-and-white Hollywood films released by a major studio in the era in which color was quickly becoming the norm.

Preminger then shifted gears repeatedly, following the old-school war movie with a gritty psychological thriller (Bunny Lake Is Missing) set in the UK and a tone-deaf racial drama (Hurry Sundown) set in — and shot in, causing considerable friction — the American South. Neither managed to burnish the director’s fading reputation. The Great Otto Preminger was suddenly box office poison.

And then came Skidoo. It was the dawning of the age of trippy LSD/hippie exploitation flicks — The Trip, Psych-Out, the Monkees’ Head and so on — and the whole “sex, drugs and rock & roll” youth culture vibe was fertile ground for an old taboo-breaker like Preminger. Electrified by all the discussion of mental and spiritual liberation through the power of positive chemistry, he even experimented with acid himself, guided by no less a psychic sherpa than Timothy Leary.

Preminger, long in the habit of adapting bestselling novels for the screen, optioned the popular college-kid-on-LSD novel Too Far to Walk for his next project. He hired a younger writer, Doran William Cannon — who had worked on the production of the massive hit The Graduate — to do the heavy lifting of crafting the adaptation, but the book was grim and heavy-handed and the younger man struggled to turn it into a screenplay worth filming. Cannon had already given the director a copy of a script he had written — a lighthearted counterculture farce titled Skidoo — and after getting nowhere with the Too Far to Walk for a few weeks, Preminger made the snap decision to drop the adaptation and shoot Cannon’s screenplay instead. It was kismet.

Paramount was horrified. One of the studio’s vice presidents reportedly begged Preminger in writing not to make Skidoo, but the old man had a seven-picture deal and he could make anything he wanted. And boy, does this film contain everything he could have ever wanted.

Skidoo is 1968 suspended in agar. Crammed end-to-end with eye-popping midcentury set design, the movie neatly balances the traditional aesthetic (and philosophical) sensibilities of the older generation of characters against the organic dayglo explosion of late-’60s youth culture, all in Technicolor and Panavision, and set to a jaunty period-perfect soundtrack by a wet-behind-the-ears Harry Nilsson. The main storyline is a dusty old standby — the retired mobster called back in to do just one last job — but in this case the story really only serves to tee up one opportunity after another to fling winking critiques at consumerism, authority, advertising, processed food, archaic social norms and the uptight squares who defend them. The fact that much of the cast is made up of outdated TV and movie stiffs — three of whom, like Preminger himself, had portrayed villains in the 1966-67 Batman television series — makes this an especially bizarre effort.

The reviews were terrible, and the viewing public took a large collective pass. Even Groucho hated it, complaining that he looked “embalmed” in the finished film. (He was nearly 80 and increasingly frail at the time of shooting. Tangentially, he was also the only major cast member known to have taken LSD before making the film, trying it under the guidance of Yippie journalist Paul Krassner.) Preminger’s career never recovered; though by the time of Skidoo he had directed 34 films in 38 years, he would make only four more over the next decade, none of which received wide acclaim. He died in 1986 after struggling for years with both Alzheimer’s Disease and lung cancer.

But this isn’t how the story ends, of course. Time has, as it so often does, softened the abysmal reputation of Preminger’s last 15 years of work, and though clunkers like Hurry Sundown will probably never be rehabilitated, younger generations of audiences are finding more and more to like in Bunny Lake, 1971’s Such Good Friends and yes, even Skidoo.

I have known of this film, which was released when I was five days old, for decades, read about it in books about both cinema and counterculture — and yet until this week had never seen it. As it turns out, a quite good print of the entire film is available for interruption-free viewing at YouTube. So I settled in the other night and watched it on the big screen. And I have to admit, I really enjoyed it. In fact, I’m gonna give it…

Grade: B

What follows is a detailed synopsis of the movie. Consider everything beyond this point a spoiler!

Skidoo starts out with a period-perfect cartoony opening title sequence that draws back to reveal itself being viewed on a large console color television. Suddenly comes the iconic click of the old Zenith Space Command remote control and the channel changes back and forth, between a showing of Preminger’s own naval war epic In Harm’s Way and various commercials preying on the sloth and insecurity of the average TV viewer, pitching beer, guns, cigarettes, deodorants and placebos. It becomes clear that two different clickers are battling for control of the television.

This movie is meta before it even starts. Carol Channing’s voice breaks in over the din of channel-clicking, complaining that watching films on television is no good because they “cut them to pieces.” (Wink, wink!) The camera finally breaks from the TV screen and we see a well-appointed living room peopled by retired mobster/car wash operator Tony Banks (Jackie Gleason), his longtime right-hand man Harry (the eternal Arnold Stang) and Tony’s beloved wife/ex-moll Flo (Channing, looking as always like a living exotic flower in a spectacular Rudi Gernreich original).

They settle on watching live Senate testimony in a hearing on mob activities involving some of their old cohorts and it’s clear that Tony is happy to have left that life behind him 17 years prior, at the birth of his daughter and only child, the honey-haired Darlene (Alexandra Hay). For a moment the grandfather of all right-wing TV cranks, Joe Pyne, is seen on-screen, commenting on the Senate hearings.

When Harry sees a familiar old car — a down-at-the-heels 1937 Rolls-Royce — coming up Tony’s drive, he thinks old enemies have come to whack them and panics, sending Tony scrambling for guns he had put away years before. We see that it is only Darlene, returning home from a date with her hippie boyfriend Stash, played by John Phillip Law in a truly insulting and ridiculous wig. Tony misunderstands the situation at first at knocks Stash out with the butt of his pistol.

Flo, having retired to the kitchen, burns a pan of sausages in a gag crafted just to shoehorn in a reference to the space age miracle product Teflon, and Stash is brought inside to indulge in a by-the-numbers generation gap scene. And just when you think you know where the movie is going next…

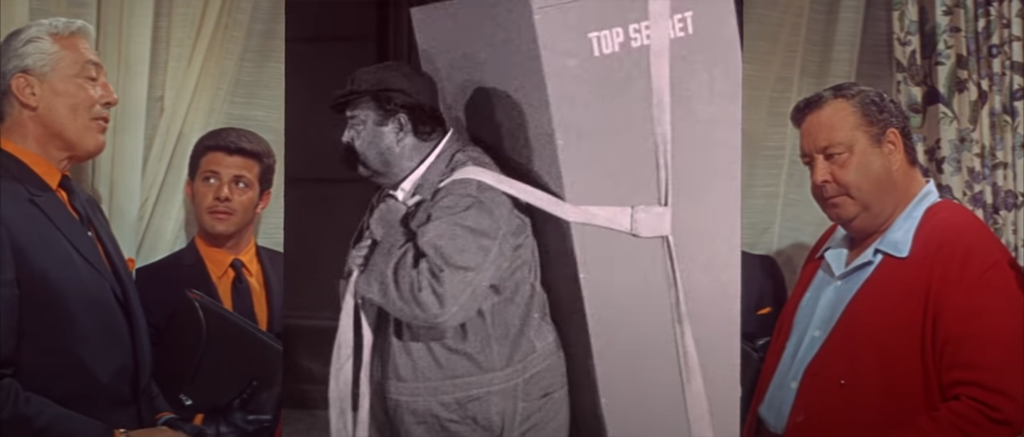

The Banks household receives an unexpected visit from fellow veteran gangster Hechy (Cesar Romero) and his son Angie (Frankie Avalon), who came under cover of darkness by speedboat. They have bad news for Tony — the top boss, known only as God, wants him to infiltrate Alcatraz undercover as a prisoner and murder the incarcerated mob accountant “Blue Chips” Packard (Mickey Rooney), who they expect to spill all the organization’s beans in the ongoing Senate hearings.

Tony objects, reaffirming his retirement in no uncertain terms and reminding his guests that he was allowed to quit the mob — and even given his new name and business — by God himself all those years ago after Tony saved the whole outfit in a daring raid on an FBI office, stealing a file cabinet full of evidence against the organization. (This is depicted in a split screen sequence straight out of the French New Wave, in which the action-packed raid scene is juxtaposed in grainy black-and-white against the bold color of the rest of the film.)

Hechy indicates there is no way out for Tony. He and Angie will be waiting for him until dawn at the old Pier 17, but Tony says they are wasting their time. On their way out they see Darlene and Stash making out in the driveway. Tony runs everybody off and goes to bed.

In the middle of the night the phone rings in Tony and Flo’s bedroom. Someone reports that the lights and machinery are on at Tony’s car wash. He gets dressed, drives down there and finds Harry’s car sitting in the middle of the wash cycle, with Harry himself dead in the front seat, shot through the center of the forehead.

Tony grudgingly accepts that he’s going to have to go through with the hit on Packard, pushes Harry’s corpse aside and drives to Pier 17 to meet Hechy and his boy. He descends to the boat and into darkness.

The movie suddenly cuts from this grim nighttime scene to broad California daylight. An encampment of rainbow-colored hippie caricatures is trolling the cops downtown, engaging in heavy petting in a parking space and complaining that they have paid the meter for the spot when the police attempt to eject them.

Inside an adjacent Merry Pranksters-style school bus, Stash introduces Darlene to his tribe of free-love freak flag flyers (real-life members of Wavy Gravy’s Hog Farm collective), who immediately begin to disrobe her and paint her body. The cops come in, get fondled by some hippie girls and ultimately arrest everybody for possession of drugs. The whole vast coterie of hippies is taken downtown to be confronted by the Mayor and a council of concerned citizens.

Flo happens to be among said citizens and when the mayor orders the hippies to move on, she is afraid Darlene will abandon her upcoming enrollment at Vassar and run off with them — so she offers to let them stay at the Banks residence (even though she knows Tony won’t like it).

Meanwhile the mob manages to smuggle Tony inside the prison, where he is assigned a cell with a recidivist rapist bookworm named Leech (Michael Constantine, most widely known today as the Windex guy from My Big Fat Greek Wedding) and incoming draft card burner Fred, aka the Professor (Austin Pendleton, who I recognized as Max from The Muppet Movie).

The older men take exception immediately to Fred’s politics, but in the interest of peace in the cell allow him to hang a copy of Tomi Ungerer’s “Kiss for Peace” anti-war poster. Tony settles in and waits for his opportunity to meet “The Man,” his gangland contact inside the prison.

Back at the Banks house, Flo has been too occupied washing the hair of one hippie after another in her kitchen sink to notice that she hasn’t heard from Tony. But she knows the previous evening’s appearance of Hechy could only mean trouble, and assumes correctly that Tony has been reactivated. She sets off for Angie’s swinging bachelor pad to put the squeeze on the young man for information on her husband’s whereabouts.

Coincidentally, while Flo is en route, Angie calls the Banks residence to let her know what she has already deduced. Darlene, still painted head to toe like an extra from Laugh-In, finds out that Angie knows where her dad is, but when he won’t tell her, she decides to take matters into her own hands and heads to his apartment, too — unaware that her mother was already on the way there.

Cutting back to the prison we see our trio of cellmates in the chow line, where Leech laments the frozen, processed food served in the cafeteria. “I remember when this place used to serve fresh vegetables from our own farm,” he says. “Now everything tastes like plastic bags.”

In the cafeteria Tony finally meets The Man (Frank Gorshin), who informs Tony that Packard will not be an easy target, as he is kept in luxurious isolation in an unknown location inside the prison — even his food is prepared separately. Tony once again objects to being dragged into the affair. If he can’t get to Packard, then why was he called out of retirement?

The Man reveals to Tony that Fred, the draft-dodger kid, had been placed in his cell for a reason. Turns out the young man is an electronics wizard, and despite his protestations of having sworn off technology, he is pressed into service in aid of Tony (but not before having his mop of hair forcibly shaved to conform to prison standards).

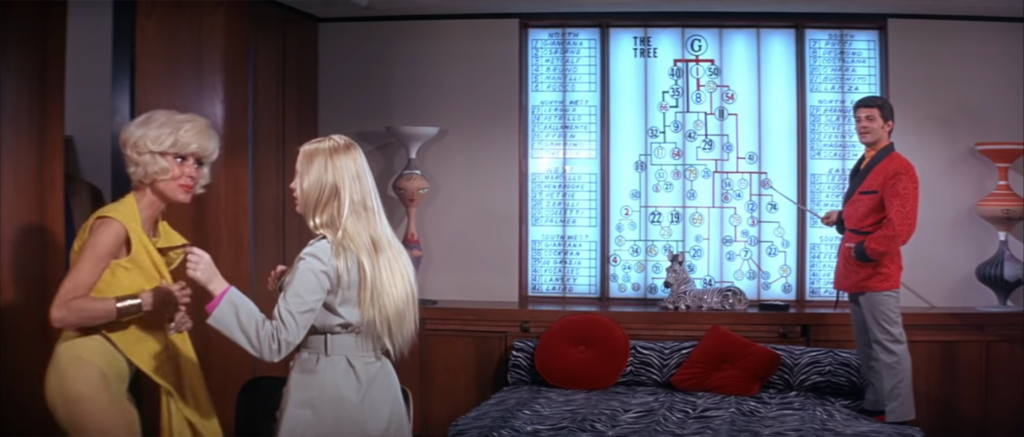

The action shifts back to Angie’s swanky, high-tech apartment, where we find the young rake clearly preparing the space for a lady caller. When the doorbell rings, it’s not the spicy redhead he has been working on for six weeks — it’s Flo. She wants to know where Tony is, and when Angie won’t tell her, Flo — fully aware she is about to cock-block the hell out of this kid — unzips herself out of another insane Gernreich creation and sprawls herself across the zebra-striped bed in only a bra, sheer leggings and knee-high yellow vinyl boots.

The doorbell rings again, and this time it’s Darlene. Angie presses a button, sinking his bed into the floor — complete with Flo atop it — and replacing it with an office set. Darlene has come to find out where her father is, but Angie quickly puts the moves on her, pouring champagne, setting the scene with low lights and soft music, and even sending the hotly-anticipated redhead packing when she finally arrives.

Darlene suddenly snaps out of Angie’s spell, and as she struggles to leave so she can search for her father, the remote control that operates the gadgets in the apartment goes haywire. Flo rises through the floor on the bed, leading Darlene to assume she and Angie are having an affair. Her mother quickly disabuses her of this notion, and as she zips herself back into her dress, Angie explains to the mystified Darlene that before she was born, her father was the top hitman in a massive nationwide protection racket called “The Tree.”

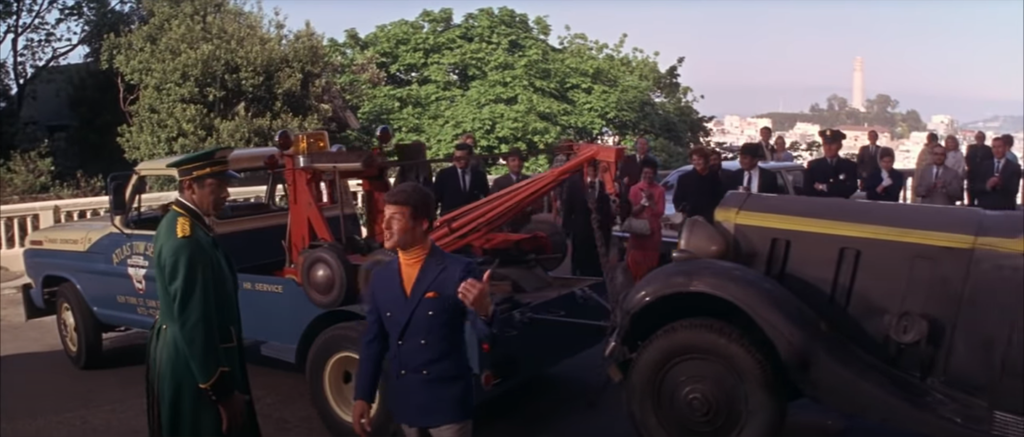

Darlene turns the charm offensive around on Angie and with a kiss convinces him to take her to see God. The three exit Angie’s posh building and find Stash, who has been waiting in the car for Darlene to return, engaged in a tug-of-war with a tow truck. Angie breaks up the conflagration and all four make their departure in Stash’s old Rolls. At the pier Angie and Darlene get in a boat to make the trek across the water to find God, and a suddenly jealous Stash leaps into the water and swims out to join them before they pull away.

Back at Alcatraz, we see “Blue Chips” Packard for the first time, in his fully-furnished office cell complete with stock ticker, telephone, television and personal butler service provided by the prison staff. He is busy making trades when he hears a distorted voice emanating from his television set.

It’s Tony, using a radio modified by his cellmate Fred to act as a two-way communicator. The pair manage to instruct Packard how to talk back by sticking a fork across his TV’s antenna connections, and the old mob cohorts have a radio reunion of sorts. Packard immediately senses that Tony’s presence in the prison can only mean that he is there to murder him, and though he admits he has the power to arrange a meeting between them, he won’t do it.

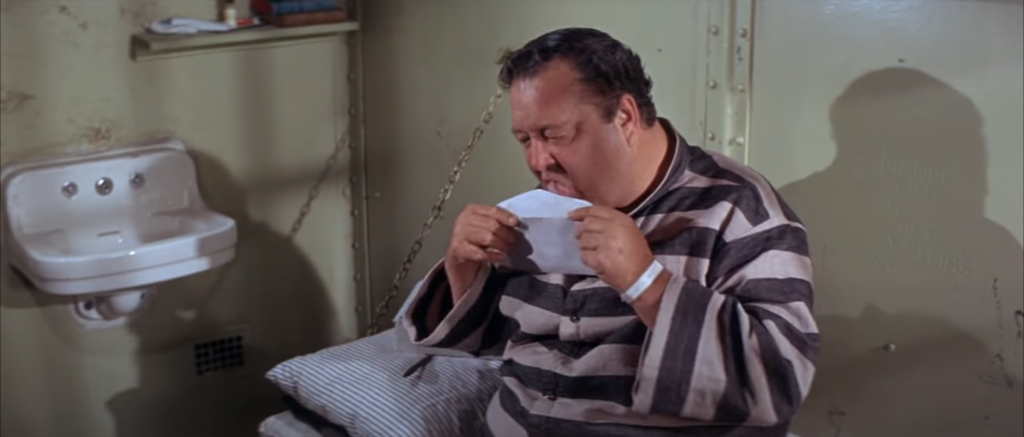

When Packard abruptly cuts off their radio signal, Tony sees his one opportunity to complete his mission and get back to retirement slipping away before his eyes. He resumes writing an unfinished letter to Flo, adding that he may be gone a long time — as his failure to kill Packard means he will most likely remain in prison the rest of his life.

And right here, Tony makes a grievous error. Having helped himself to some of Fred’s stationery, he folds up the letter, slides it into an envelope, then licks the adhesive seal just as we’ve all done countless times before. How was he to know that the Professor’s personal stationery was soaked in LSD?

The ever-empathetic Fred leaps into action, gently informing Tony what has just happened and preparing him for the high-octane psychedelic voyage upon which he is sure to be embarking any minute now. Tony has heard of LSD on the news, and though he is understandably nervous, he has by now built enough trust in the Professor to let the younger man guide him through his experience.

Here the film cuts to international waters, several miles off the California coast, where God (Groucho Marx) lives in self-imposed exile on a yacht named (in rather Freudian fashion) Mother, on which he plays bumper pool with his supermodel mistress Elizabeth (the tall, rail-thin, black ’60s cover girl Donyale Luna). A paranoid germophobe, God never leaves his cabin, which is separated from the outside world by a vault door. He keeps an eye on the things he needs to see with a large television monitor, through which he can access a myriad of cameras and intercoms.

God is less than happy to hear from his skipper (classic Hollywood tough guy George Raft) that visitors have arrived. Suspicious of Stash with his long hair, God dispatches Elizabeth to frisk the incoming party. After some two-way communication over the intercom, God allows Darlene to come into his inner sanctum — but only after she’s been given a hot bath to decontaminate her.

Back in the cell at Alcatraz, shit is about to get weird.

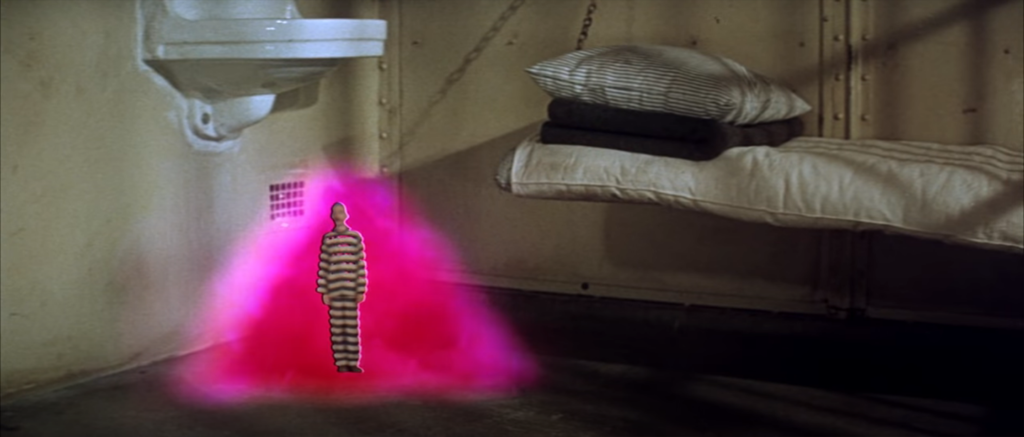

As Fred gently coaches him along, Tony’s acid trip begins in earnest. He starts sweating bullets. Then the hallucinations begin. He sees eyeballs staring back at him from the bunk bed frame above his, then pictures the Professor and Leech as tiny versions of themselves, surrounded in a swirling miasma of pink and purple haze.

Tony lies back down and imagines a Thompson submachine gun with its barrel bending like wet spaghetti, shooting ratatat! and writing numerals on the blank canvas of his acid-drenched mind. The sight of this prompts Tony to laughter. When Leech asks what’s so funny, Tony replies, “Mathematics! I see mathematics!”

Next, Tony appears to be momentarily beset upon by unseen insects, at which he snatches repeatedly, to no avail. And this brings us to perhaps the single most bizarre shot in all of Preminger’s filmography.

Yes, after Leech suggests Tony “has a screw loose,” Tony hallucinates a screw, bobbing and spinning around the cell — topped by the waxy rotating head of Groucho Marx, complete with cigar. Tony says, “Aw, no… I’m not playing your game,” and watches the Godhead Screw drop down the grubby hand sink in the cell.

Feeling better, Tony splashes his face with water from the sink, and Fred encourages him to “look for yourself, Tony. Find yourself in the water.” Tony peers deep into the water and enters the next phase of his trip through his own reflection.

I must explain here that there has been a running gag throughout the picture, in which practically every man Tony speaks to inquires about Flo, with the unspoken implication that they have all slept with her. As Tony enters this intensely self-reflective segment of his acid trip, he immediately fixates on the question of Darlene’s paternity. It’s obvious that he loves her and is proud of her, and would be even if she was revealed to be another man’s child, but, as he mumbles repeatedly, “A father’s got a right to know.”

Tony finds himself confronted with a kaleidoscopic panoply of voices and images and faces and music. There’s Blue Chips dancing around in the center of the action, taunting Tony with two giant bags of money while the other players in his life — his wife, his daughter, the Senator from TV, God, Hechy — carom around the periphery. Flo appears and Tony asks her directly about her extramarital affairs, then decides he doesn’t want to know. Flo reassures him that Darlene is obviously his daughter, as she has his ears. The sudden delight he takes at this realization is just as quickly crushed when he is confronted with the specter of poor Harry, shot dead through the windshield of his car, speculating that he thought he was probably Darlene’s father. “Sorry, Tony,” says the dead man. “It’s just one of them things.”

Tony asks for a flower and Fred hands Leech an upturned shaving brush, cueing him to hand it to the tripping man — who accepts it with a smile, having perceived Leech as Flo. Fred, clearly proud of Tony, announces, “He did it. He lost his ego!” The worst of it is over.

On the good yacht Mother, God has a handsy heart-to-heart with Darlene, explaining to her that her father — “the best torpedo in the business” — is in prison, but safe and sound. Elsewhere on board, Elizabeth chases down the initially reluctant Stash, with whom she has found herself smitten. Predictably, it doesn’t take her long to whittle down his defenses.

Back in prison, Tony has recovered from his trip when The Man visits his cell, bringing him trusty credentials and a knife with which to kill Packard. In the proposed new plan, Tony will take the place of the guard delivering Packard’s corn flakes, giving him the opportunity to make the kill. But Tony wants no part of it and refuses the job.

The Man reminds Tony that his refusal means losing his freedom forever, and adds that Darlene is on God’s boat at that moment, and in mortal danger should Packard live through the day. As The Man leaves the cell, Tony breaks down in tears at his predicament. Fred, once again showing immense compassion for Tony, vows to use his intellect to solve this problem.

Once again on the yacht, God has the first in a series of frustrating video/phone calls. Waking Stash in his cabin via remote viewer, God makes him a business pitch, proposing a partnership in a nationwide drug distribution network run by young longhairs. Replying that while he does like money, he is bored by business, Stash rejects the offer and rolls over to return to sleep.

Next, God gets a call from The Man inside the prison, breaking the bad news that Tough Tony has gone soft. Furious, God then pages Angie in his cabin, where he is sleeping with the clearly frisky Elizabeth. (Fortunately the camera is obscured by her bra, preventing God from witnessing this dalliance. ) God tasks Angie with murdering Darlene, should Tony fail to come through with his assignment.

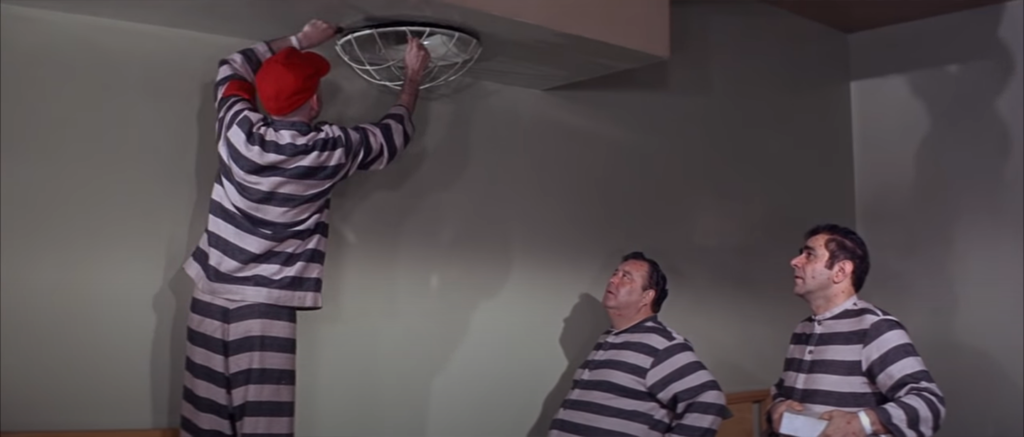

Back at Alcatraz, our three cellmates set their escape plan in action, faking “Lithuanian Measles” to get into the infirmary. From there Fred crawls through the vents to the kitchen, where he dumps his sizable stash of LSD into the evening’s meal. Tony manages to get into the walk-in freezer, where he starts cutting up the giant plastic bags in which Reddy-Freddy frozen foods are shipped.

Unbeknownst to any of the crew, the Senator (Peter Lawford) in charge of the mob hearings just happens to be visiting the prison in order to meet with the Warden (Burgess Meredith) and have dinner with the prisoners. (You can see where this is going, right?)

Returning to the yacht, we see Elizabeth going behind God’s back, warning Stash that he and Darlene are in danger. Stash pretends to agree to God’s business proposition, on the condition that he can make a phone call to make sure he can hold up his end of the deal.

Stash calls the Banks house and asks for Geronimo (played by Law’s real-life brother Tom Law), then feeds him a coded message that tells Flo and the caravan of hippies exactly where to find them.

Cutting back to the prison we find the entire population and staff tripping their brains out in the cafeteria. The Man hallucinates an image of himself as an angel. Beany the trusty (Richard Kiel) begins grabbing each person around him in turn, looking for his lost “Loretta.” The liberal Warden dreams aloud of his vision of a prison in which inmates are perfectly computer-matched for compatibility, provoking the sweating Senator to leap to his feet in a sudden burst of fiery oratory. The distracted Warden willingly hands the prison keys over to the Professor, and our trio moves on to the next step of their escape plan.

God attempts to call The Man back for an update on Packard’s assassination, but can’t get through the prison switchboard operators (Slim Pickens and Robert Donner), who are goofed out of their gourds. He ends up patched to the prison kitchen, which has descended into chaos.

Tony, Leech and Fred begin gathering up items — giant frozen food bags, canisters of compressed gas, etc. — and hole up in the prison’s sewing shop. Outside, a pair of acid-soaked tower guards overlooking the prison yard (Harry Nilsson and Fred Clark, who died two weeks before the film’s release) watch prisoners busily moving large galvanized steel trash cans out of the facility. The older guard sees them as a nude vision of the Green Bay Packers football team; moments later the cans move on their own, getting up and dancing in a spectacular solarized psychedelic light show performance of Nilsson’s “Garbage Can Ballet.”

At the end of the musical number, the guards are too blasted to do anything about it when Tony, Leech and Fred begin the final stage of their escape in plain sight, unloading the various items they have cobbled together from a dumpster and scurrying away with them.

Completely by accident, the switchboard operators connect God with Packard, blissfully unaffected by the mass dosing of the evening’s dinner, as he has his own food supply. Needless to say, God is quite annoyed to find Blue Chips still alive and well. Their brief call is abruptly terminated when one of the operators disconnects the line.

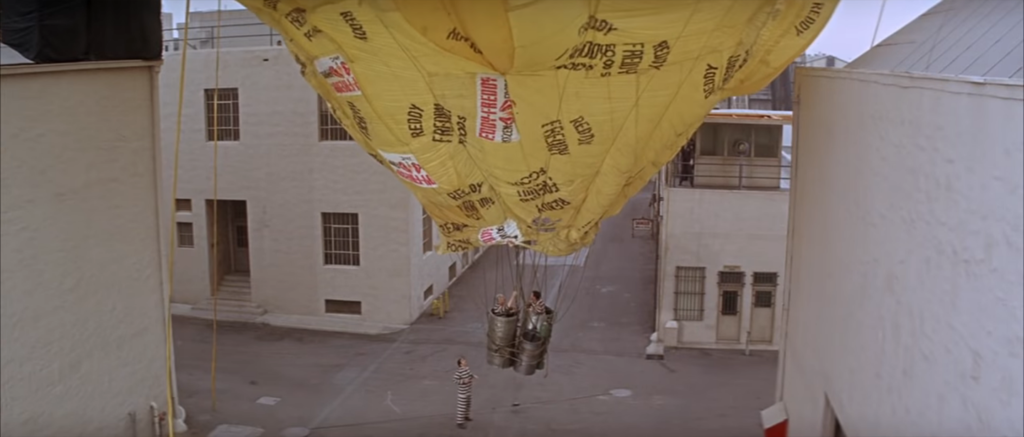

Day breaks and Tony and the Professor make a getaway in their makeshift hot air balloon, which is only big enough to carry the two of them — forcing them to leave Leech behind. The majestic airship, stitched together from the purloined frozen food bags, soars away into the sky to the tune of Nilsson’s “Man Wasn’t Meant to Fly,” sweeping the two men out to sea and ever closer to God’s yacht.

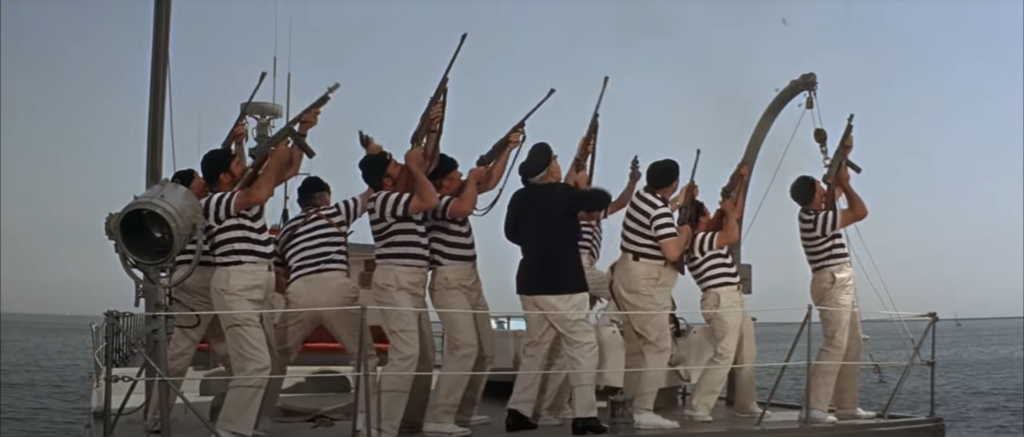

Meanwhile on that very yacht, God gives Angie the order to whack Darlene, and watches from his sealed cabin via monitor as Angie sneaks into the young woman’s bathroom with his pistol, shuts the door and fires. Satisfied that she has been taken care of, God is just about to go about his business when the Skipper announces the impending arrival of what looks like a flotilla of “friendly natives.” God calls out his security squad, but they quickly find themselves faced with the dilemma of whom to shoot at — the hippie navy approaching from astern or the hot air balloon suddenly descending from above.

Resistance turns out to be futile, and the yacht is boarded by both encroaching parties at once. Sensing certain personal jeopardy, God fakes a getaway, opening the vault door to his cabin, but hiding inside a closet therein. The balloon deflates, covering most of the deck just before the lead small craft reaches the yacht’s stern, captained by Flo — now dressed in a bespoke John Paul Jones getup complete with waist-length blonde wig. She leads the charge onto God’s vessel and leads the invading force of flower children in a rousing rendition of the film’s theme song, accompanied by members of the real-life RCA Records recording act Stone Country, as the entire ship is engulfed in bedlam.

Tony finds Darlene holed up with Angie, who it turns out had (like Tony, Elizabeth, Packard and Stash) betrayed God — by faking his murder of Darlene. Flo leads the hippie invasion into God’s inner sanctum, and they happily help themselves to the many creature comforts inside as she continues singing the theme. Tony enters, angrily looking for God. “Have you seen God? Where is God?” he asks various members of the crowd, none of whom has an answer. Finally he and Flo are reunited, and she gently shushes him and leads him to a private cabin, where they kiss passionately, fall into bed together and shut the door to the world.

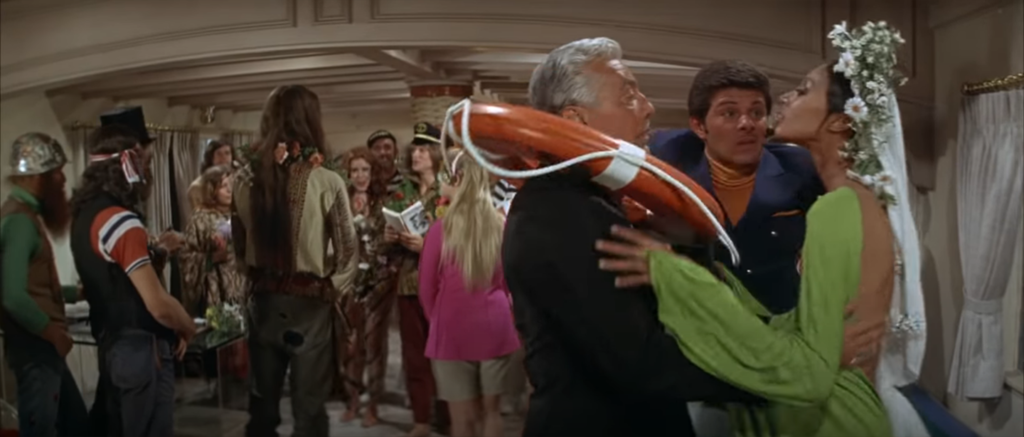

The action cuts back to God’s cabin, where the Skipper is performing a sea wedding, uniting Elizabeth and Angie. In place of a Bible, he holds a copy of Gabriel Vahanian’s iconic The Death of God; in lieu of a wedding ring, Angie gives to his bride one of the ship’s bright orange life preservers, emblazoned with the word MOTHER. Immediately after the wedding kiss, Elizabeth turns to Angie’s father Hechy, places the big buoyant ring around his neck and leads him off to the side, where she smothers him with kisses, over the protests of her new husband. In the same shot, we see the Skipper hand his hat and book to Geronimo, who promptly begins a second wedding ceremony — uniting Stash and Darlene.

The camera cuts away to a shot of a small sailboat, its sails gaily painted with brightly-colored flowers and the words LOVE and PEACE. In it are two figures, shrouded in robes, beads and flowers reminiscent of Hare Krishna garb. It’s God and the Professor, both set free from their respective prisons, smiling beatifically and passing a joint back and forth on a roach clip.

Just when you might expect to see THE END superimposed on the screen, the film freezes and Otto Preminger’s Teutonic voice breaks in. “Stop! We are not through yet! And before you skidoo, we’d like to introduce our cast and crew.” This is followed directly by the end credits, the entirety of which are sung by Harry Nilsson, accompanied by a second animated title sequence. This movie came in meta, and it goes out meta.

So after all that, if you’re still reading, surely you can see why I feel this movie is better today than when it was made. It’s still an absurd, jumbled mess of caricature, hokum and performative edginess, make no mistake — but as an artifact from the era in which it was made, it captures (intentionally or not) so much of the zeitgeist of the time that it holds its own easily against any number of contemporary films that have traditionally been held up as touchstones of the day.

And I haven’t been able to get the theme song out of my head, either.

I missed this particular article the first time around, read it this morning, and watched the movie after that. It really is campy in the best nostalgic way, and the cast is pretty incredible. I am a big Nilsson fan and got a kick out of his scene in the movie, as well as his music. Being as I had never even heard of Skidoo before, I want to thank you for introducing me to it. Lots of fun! Thanks, Michael!

It’s a wild ride, for sure!