The latter half of the 1990s was a transitional time for the music industry. Production of vinyl records had petered out almost entirely and the long-popular cassette format was plummeting from favor, too — both supplanted by the compact disc, which itself now faced an existential threat in the form of the humble digital MP3 file format. Changing technology suddenly allowed music lovers to free themselves altogether from the chains of physical media, and the rise of peer-to-peer file sharing networks such as Napster gave them the ability to collect as many songs as their hard drives would hold — entirely for free.

None of this really much affected the bottom lines of major label marquee stars, despite the outraged protestations of human prune Lars Ulrich. The heavy hitters were still on commercial radio every day, scoring with big-budget MTV videos and major publicity campaigns. But what of the indies?

Just a handful of years before, at the dawn of the ’90s, there had been a thing called “alternative music,” a brilliant and beautiful creature which made its home in the robust network of local college radio stations that dotted the American landscape — and on MTV’s stalwart alt-rock omnibus 120 Minutes as well. Made up primarily of acts on independent labels such as Twin Tone, IRS, Homestead, Shimmy-Disc, Flying Nun, et al, some of the top names in the field were beginning to gravitate to majors, starting with Hüsker Dü’s defection from the iconic indie SST Records to no less than Warner Brothers. So deep was the association between alternative rock and college radio that the official trade publication of the biz was called College Music Journal.

But then came the one-two punch that altered the indie rock playing field forever.

First there was the nationwide trend of replacing organic local student programming on public radio stations with slick canned content from NPR and PRI. Almost all at once, it seemed that America’s public radio, long a beloved vehicle for idiosyncratic local and regional voices, was transformed into a homogenous coast-to-coast chorus of All Things Considered and Fresh Air. In a majority of cases, as happened in Wichita in 1990 (see video above), the very first thing to be cut was alternative music programming — and the student on-air talent was consistently thrown under the bus as the reason.

The second blow came out of nowhere when David Geffen signed a cheeky, gritty rock trio out of Aberdeen, Washington — and their album sold 30 million copies. So began the “Grunge Gold Rush.”

The skies over Seattle were suddenly darkened as industry hacks from LA and NYC parachuted into town by the thousands, clutching briefcases full of money in one hand and recording contracts in the other, ready to hit the ground running and sign the first dude they saw on the street carrying a guitar.

Countless young musicians with stars in their eyes signed on with established labels who were looking for the next Nirvana — and a huge number of them found themselves chewed up and spit out after those labels decided they were worth more on the books as tax write-offs than as artists. By the mid-’90s, the scales were falling from the eyes of indie musicians, as they realized that the exposure and distribution opportunities associated with major label affiliation meant potentially losing their independence, and in many cases, their master recordings and a large portion of their royalties too.

With college radio strangled and dwindling underdog representation on MTV as alternative rock became corporate rock, how was a fan of underground music supposed to find out about new acts, to hear new sounds?

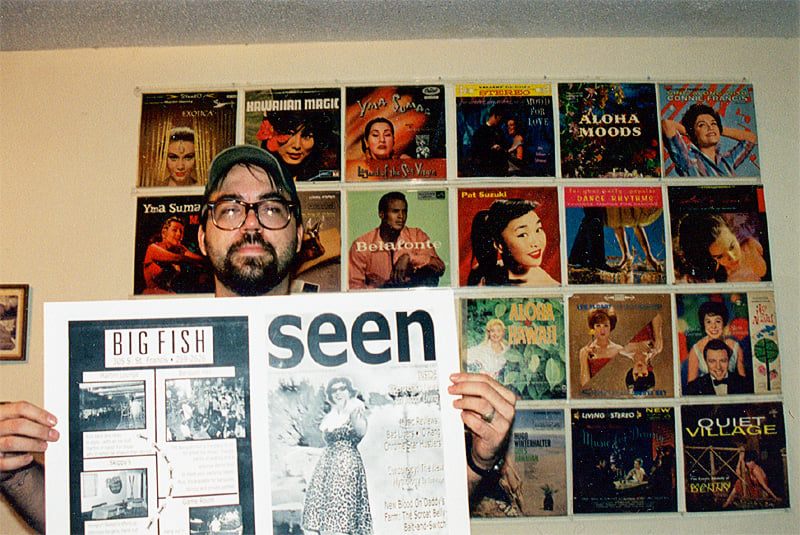

It was in this era that I started publishing a monthly music/art/culture tabloid called Seen. Though there would be only a dozen print issues and a further eight internet-only editions over the course of two or three years, Seen served at least as a sounding post for the community of music weirdos, art freaks and counterculture warhorses which had been fractured with the unforeseen demolition of KMUW’s After Midnight in 1990.

As publisher of such a rag, I was mailed a vast quantity of brand-new promo albums on CD for review, not to mention being put on the press guest list at concerts and given the opportunity to interview many musicians I admired — John Linnell from They Might Be Giants, Helium‘s Mary Timony, Superchunk‘s Laura Ballance, Robert Sledge from Ben Folds Five, Spoon‘s Britt Daniel, Shimmy-Disc heroes Dogbowl and Kramer and numerous others. Several local writers went out and did interviews on their own, then handed them to me for publication, too; I was very happy to run exclusive talks with Lemmy Kilmister, Fishbone’s Angelo Moore and Henry Rollins, among others.

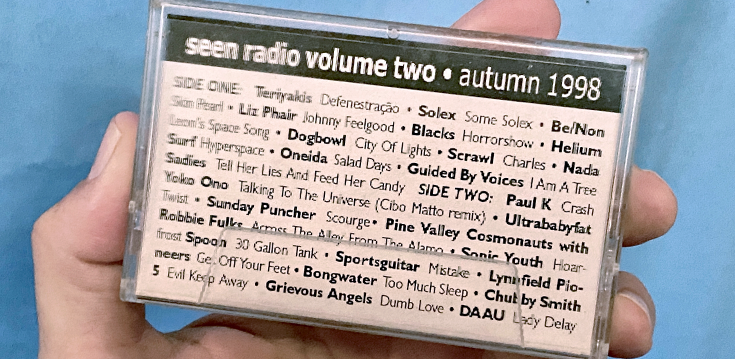

I wanted to start a 24/7 Seen internet radio station but in those days we were still using dialup modems and the quality of streaming music was at best roughly comparable to today’s best telephone hold music. All I could do to help spread the musical gospel was listen to as much new material as possible and try to review it fairly. I heard a lot of indie music in that period, and there are a few albums from then that became lifetime faves — Helium’s majestic, mystical The Magic City, Elliott Smith’s intimate XO, Sportsguitar’s woefully overlooked guitar pop masterpiece Happy Already and Neko Case’s haunting Furnace Room Lullaby among them.

Now I look back from 20+ years down the road, and as someone whose only permanent physical archive of music is a collection of several thousand LP records, I find myself wishing more and more to see these titles issued on vinyl, as most were released only on compact disc and/or cassette. It’s like a whole chapter of my musical life exists only in the aether for me, subject to the vagaries of Spotify, Apple Music and other streaming services of their ilk.

And so it’s come to this: a musical tour of the Seen offices circa 1997-2000 or thereabouts, delivered perhaps ironically via Spotify. Forty tracks in all, about two and a half hours in length. Guaranteed to take you back to the era of Frasier, Windows 98 and the Lewinsky scandal!

What would you add to this list? Honk Plus subscribers please tell me in the comments.