When I was a kid growing up on the Cherokee Strip in the 1970s, the air was filled with country music, played and sung by a cast of colorful characters so ubiquitous in my environment that they practically seemed like aunts and uncles. George and Tammy, Waylon and Willie, Porter and Dolly, Conway & Loretta, Buck Owens & Don Rich, Roy Clark, Johnny Cash, Don Williams, the entire Hee Haw crew — and of course, The Storyteller himself, Mr. Tom T. Hall. By the time I was seven or eight years old, I was already a fan of Hall’s deceivingly simple songs, plain and direct enough to reach a child, yet so meticulously crafted that the best of them can still move me to tears today, as a middle-aged man.

So I was saddened last August to read the news that Tom T. Hall had died in his home in Franklin, Tennessee, at age 85 — and then again, doubly so, just a couple weeks ago, when I learned that his death had come as the result of a self-inflicted gunshot to the head. I wondered, as I am sure many did, what had led him down that lonesome path, but in the end that is not my business to speculate upon. One can only be thankful that he is no longer plagued by whatever suffering drove him to such desperation.

At the time of his passing it had been 35 years since he had cut a hit record, and a decade since he had last set foot on a stage, but Hall left behind a legendary body of work, earning him gold records, Grammy and CMA awards, near-universal respect among the songwriter community, a spot in the Grand Ole Opry, plus permanent enshrinement in the Kentucky Music Hall of Fame, the Country Music Hall of Fame, and —dearest to his heart — the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

But accolades like these were not yet a distant dream in the days of Hall’s humble youth. Born during the Great Depression to an impecunious brickmaker/preacher in Tick Ridge, Kentucky and christened Thomas Hall — no “T.” — the young man had to share his household’s meager resources with seven siblings. He distinguished himself with his intelligence and creativity, writing poems and stories and picking up the guitar while still in elementary school. By age nine — when he wrote his first song — he had fallen completely into the thrall of a teenaged neighbor boy, Lonnie Easterly, who played guitar in a regional band. The older boy’s slow and agonizing death (most likely from tuberculosis) at age 20 crushed young Tom, but would later inspire one of his most celebrated songs, “The Year That Clayton Delaney Died.”

As a teen Hall put together a touring bluegrass band called the Kentucky Travelers, who provided entertainment before movies at a traveling theater. This group sometimes played live on area radio stations, and after Hall’s departure would even go on to record a number of sides for Starday Records. Hall took a shine to radio and got a gig as a DJ, which led to making extra pocket money writing radio jingles.

But the young man grew bored running around in small circles, and to better widen his horizons, Hall joined the Army in 1957. Stationed in Germany, he became a popular fixture of Armed Forces Radio, which allowed him to perform his funny songs about military life on the air. Back in the States, in order to sharpen his writing skills, he signed up for journalism classes at Virginia’s Roanoke College, where he once again took a DJ job. He married Opal McKinney, also known as Hootie, a woman ten years his senior. She became pregnant —but it appears there was a falling out between her family and Hall, and he moved to another town, leaving Hootie and his unborn son Dean behind. (Spoiler alert: They would reunite happily later on.) The whole time, he continued honing his craft, composing countless songs and trying to get them noticed by anybody, anywhere.

In 1963, somebody, somewhere noticed. Grand Ole Opry star Jimmy C. Newman (the “C” stands for “Cajun”) liked Hall’s song “DJ for a Day” so much that he not only recorded it, but offered the young Hall a salaried job as a songwriter at Newkeys Music, the Nashville-based publishing house Newman co-owned with country impresario Jimmy Key. Hall jumped at the chance; he moved to Music City and was soon making $50 a week grinding out songs, sometimes as many as six a day. (As a bonus, it was Key who gave Tom Hall his “T.,” suggesting it would make his rather pedestrian given name stand out.)

Unfortunately, though his talent was obvious to anybody who listened, Hall had a problem: The literary, thought-provoking, often first-person narrative style of his songs was simply too weird for many of the established Nashville names to consider recording. Hall couldn’t get arrested on Music Row.

And then in 1965, things started looking up. Dave Dudley recorded no fewer than five Hall compositions, Flat & Scruggs did one more, and Johnnie Wright — half of the iconic country duo Johnnie & Jack, not to mention Mr. Kitty Wells — took Hall’s gung ho “Hello Vietnam” all the way to number one on the country chart.

One might think this would have led a flock of artists to Hall’s front door — but it didn’t. Nashville’s biggest stars continued staying away in droves, rejecting song after song. Hall grew more and more frustrated, and might have given up, had it not been for Jerry Kennedy.

Kennedy, a session guitarist and talent scout for Mercury Records and its subsidiary, Smash, recognized the young songwriter’s brilliance and proposed Hall record his own songs himself. This had never been Hall’s intention, as he was perfectly happy working behind the scenes, and had little desire to become a recording artist, with all its attendant touring, and gladhanding, and publicity. But Kennedy was willing to sign him as a singer, and Hall figured at least this way, his work would see the light of day, and maybe stir up more interest from other artists.

Hall’s first single, “I Washed My Face in the Morning Dew,” surprised everyone at Mercury by making the Top 30 on the country chart in 1967. For much of the next year he treaded water, releasing a couple more singles that went nowhere, selling a couple songs to other artists, and hoping for another hit.

And boy, did he ever have a hit.

Aspiring singer Jeannie C. Riley, herself the secretary of another Nashville songwriter, recorded Hall’s sassy, timely, quasi-feminist “Harper Valley PTA” — and her version not only topped the country chart, but also skyrocketed straight to number one on the Billboard Hot 100, the first time in history a woman hit the top of both charts with the same song. (Dolly Parton would do it again 13 years later with “Nine to Five.”) The single sold six million copies, and in its second week on the Hot 100, jumped from number 81 to number seven, the greatest one-week leap of any single of the 1960s.

All eyes (ears?) turned to Hall, and he responded with his own recording of another humorous story song, “The Ballad of Forty Dollars” — which shot to number four on the country chart. Thus began a decade-long streak of 35 (thirty-five!) singles in a row to make the country Top 40, including seven number ones.

Suddenly everything seemed to come together for Tom T. Hall. He had by this time married the love of his life, English-born Dixie Dean — herself a hit songwriter — and a stream of classic songs poured like water out of him, each eagerly lapped up by millions of radio listeners across the continent and abroad. Other artists still occasionally hit with his material, too; Bobby Bare took the marital infidelity drama “Margie’s at the Lincoln Park Inn” to number four, and Hall’s 21-year-old protégé Johnny Rodriguez became the youngest person ever to top the country chart with “You Always Come Back to Hurting Me.” But Hall no longer relied on others to interpret his songs. He was now comfortable cranking out his own hits in the studio, and he found that his years in radio had amply prepared him for life in front of TV cameras, too, where he never failed to project an air of gentlemanly Southern charm. He was now self-contained, and as it turned out, despite his earlier misgivings, that suited his stubborn independent streak just fine after all.

Here is a short glimpse at just a few of the timeless hits Hall wrote and recorded over the next decade:

Homecoming (1969, #5) • “I guess I should have written, Dad, to let you know that I was coming home. I’ve been gone so many years I didn’t realize you had a phone.” A traveling country musician drops by his rural family home briefly after being away a long, long time. He makes small talk with his father about the old man’s cattle, inquires about some of the town folk, and apologizes for having missed his mother’s funeral — “I was on the road and when they came and told me it was just too late.” It’s as devastating as any short story I have ever read. The saddest Tom T. Hall song I know of. I cry literally every single time I hear it.

A Week in a Country Jail (1969, #1) • “One time I spent a week inside a little country jail, and I don’t guess I’ll ever live it down. I was sittin’ at a red light when these two men came and got me and said that I was speeding through their town.” A salesman passing through a backwater burg is arrested and held for days in a cell with seven other men before finally being able to see a judge. The jailer’s “awful” wife brings in daily rations of unpalatable hot bologna, eggs and gravy, but at least the narrator and his cellmates are allowed to pool their money and send the jailer out for beer, so it’s not all bad.

The Year That Clayton Delaney Died (1971, #1) • “I remember the year that Clayton Delaney died.

Nobody ever knew it, but I went out in the woods and I cried.” Hall’s ode to his childhood guitar hero, Lonnie Easterly. The name “Clayton Delaney” was cobbled together from two street names.

(Old Dogs, Children and) Watermelon Wine (1972, #1) • “Ain’t but three things in this world that’s worth a solitary dime — but old dogs and children and watermelon wine.” Hall appears as himself, a troubadour on the road, “pourin’ blended whiskey down” alone in a lounge in Miami. His solitary reverie is broken when the “old gray Black gentleman” who cleans the place engages him in philosophical conversation about the things the older man has come to find precious and meaningful in life. By the end, Hall is inspired to write the song we are listening to: “When he moved away I found my pen and copied down that line.” And indeed, the song was in fact based on an actual conversation between Hall and a porter in Miami, during the Democratic National Convention in 1972. Rather strangely, “Watermelon Wine” enjoys remarkable popularity in Great Britain, despite never having been released as a single there.

Ravishing Ruby (1973, #3) • “Ravishing Ruby, she was a truck stop child, born in the back of a rig somewhere near LA.” Unlike many of the other songs here, the narrator is not the protagonist in this one. Instead he sketches a portrait of a comely truck stop waitress who rejects the ceaseless advances of the truckers, as the only man she cares about is “Smilin’ Jack” — the father who abandoned her.

I Love (1973, #1) • “I love little baby ducks, old pickup trucks, slow-moving trains and rain. I love little country streams, sleep without dreams, Sunday school in May and hay. And I love you too.” Here Hall takes a page from the Fred Rogers lyrical playbook, stripping away his usual arch humor and tendency toward verbosity to deliver perhaps his gentlest, most sincere tune — practically a lullaby. The song became a runaway hit, easily topping the country chart, and making it all the way up the Billboard Hot 100 to number 12, Hall’s only appearance as a recording artist on the pop Top 40.

Country Is (1974, #1) • “Country is sittin’ on the back porch, listenin’ to the whippoorwills late in the day.” Sort of a more nuanced “I Love,” in this song Hall conjures up scenes that he purports to mean “country,” though some of the examples — “Country is teachin’ your children ‘find out what’s right and stand your ground'” for instance — may not be so black-and-white as they appear on the surface.

I Care/Sneaky Snake (1974, #1) • Technically, the a-side of this single is “I Care,” which went to number one on the country chart — but as a kid, it was the b-side that was the big hit in our household. Both tunes were from Songs of Fox Hollow, Hall’s album of music written for children, which itself went to number three on Billboard’s country album chart. Once again he channels Mr. Rogers in “I Care,” a tender song of support, consolation and reassurance. After listing a number of situations that might make a child sad, or scared, or bored, Hall reminds the young listener: “I care, I do. There’s no one like you. And sometimes I act like a grouchy old bear — I want you to know I care.” The b-side is entirely different, a funny uptempo number alerting children about a certain pilfering reptile. “Boys and girls take warning if you go near the lake — keep your eyes wide open and look for the sneaky snake.” But in the end, this snake isn’t out to bite anybody, he just wants to giggle, dance and, if you’re not careful, steal your root beer! This song was my absolute jam in 1975, and my kids today have a copy of not only the Fox Hollow album (complete with full-color booklet!) but the “I Care/Sneaky Snake” 45, too.

I Like Beer (1975, #4) • “In some of my songs I have casually mentioned the fact that I like to drink beer.” ‘Nuff said!

Faster Horses (The Cowboy and the Poet) (1975, #1) • Another short story song in the mold of “Watermelon Wine,” with a young poet asking a wizened old cowboy about “the mysteries of life,” only to be told the answers lie in “faster horses, younger women, older whiskey and more money.” The narrator takes issue with this, but is put in his place by the old cowhand: “I told him I was a poet, I was lookin’ for the truth. I do not care for horses, whiskey, women or the loot. I said I was a writer, my soul was all on fire. He looked at me an’ he said, ‘You are a liar.'” This was Tom T. Hall’s last number one song.

Your Man Loves You, Honey (1977, #4) • “Had my golf clubs on my shoulder when you saw me first today, wearin’ my old army sweater that you thought you threw away. And when you saw me standin’ there you shook your head and sighed — when you saw I’d bought a six-pack, I thought you were gonna cry.” A song from an obstreperous husband to his long-suffering wife; they both know he’s incorrigible but at least he’s loyal, and he hopes it’s enough.

The Old Side of Town (1980, #9) • “Ain’t it strange how people change, and almost overnight? Who once was a country girl is now a socialite. We’re proud for you, but when you’re through and seek some common ground — oh, we miss you on the old side of town.” A love letter to a friend (or maybe an old lover) who may have gotten too big for her breeches.

And these are just the cream of the crop. Let me say it again: On top of these, Hall put almost two dozen additional singles — literally every one he released — into the country Top 40 in this span of time. He was as bankable a star as anybody Nashville had to offer and it seemed he could do no wrong. Chevrolet hired him as the public face of their truck division and he made numerous commercials for them through the mid-to-late ’70s, and “Harper Valley PTA” was revived as a feature film, and then a TV series, both starring Barbara Eden as the song’s “Mrs. Johnson.” In 1980 he replaced legendary country butthole Ralph Emery as the host of the syndicated TV series Pop! Goes the Country, which also gave Jim “Ernest” Varney his first regular coast-to-coast television exposure.

But by the mid-’80s, country music had changed a lot. A generation of young country artists had moved in, bringing with them fresher, more modern, pop-oriented sounds. Alabama, Rosanne Cash, the Judds, Reba McEntire and others began squeezing old artists off the charts, and Tom T. Hall was no exception. He made the Top 40 twice in 1984 and ’85 — both times, uncharacteristically, with songs written by others — and then slowed way, way down. After 1986 he issued only three albums of new material, and no further singles.

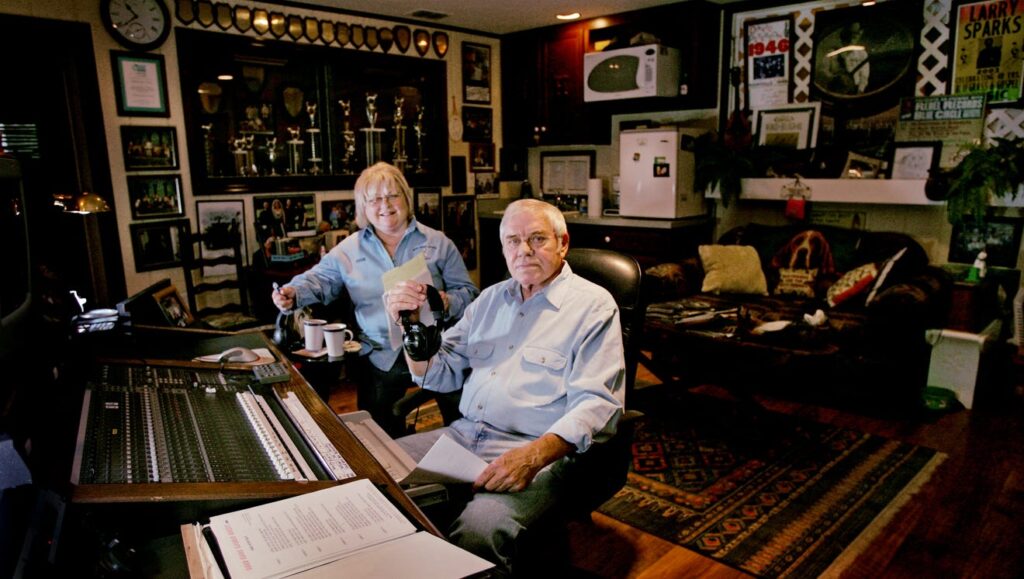

Hall tried to retire altogether from music in the 1990s but his wife, Dixie, refused to stand by and watch him let his talents go to seed. She challenged him to get back to work and he agreed, on the condition that she would, too — and so they both got busy writing, separately and together. In 1996, one of Hall’s new compositions, “Little Bitty,” was recorded by Alan Jackson — at the time one of the hottest country stars on the planet — and it went straight to number one. Dixie put the proceeds to good work, turning the dog kennel in their house into a recording studio, founding an independent bluegrass record label and setting up a music publishing house.

Tom T. and Dixie spent the rest of their lives writing and farming out bluegrass songs, winning awards — including ten straight Songwriters of the Year awards from the Society for the Preservation of Bluegrass Music of America — and enjoying one another’s company. Dixie’s health went into decline; at the time of her death in January 2015, she had set a record for the greatest number of recorded bluegrass songs ever written by a woman (with over 500!), and she and Tom had been married for 46 years.

And now Tom has gone to join her, leaving behind his own remarkable music legacy. I consider myself lucky to have grown up in a time when his warm voice, humanistic philosophy and gentle good humor were so omnipresent, he felt like a real part of my family. There won’t soon be another like him.