This is a true story and includes discussion and links related to the traumatic events of 9/11. It also details the period of my life in which I was prescribed a series of psych meds, during which the terror attacks occurred. Those sensitive to either topic are hereby warned. Please know that despite my own lack of success in treatment, I am aware that many people do very well on the sorts of pharmaceuticals mentioned in this story. This is not intended in any way to be critical of these medications or those who take them. It is merely an honest account of my own personal experience with them. Thank you. — MC

Lucy and I got married in October 2000 and enjoyed a lovely nine-day honeymoon in New York City, a place I had never been. It was the first, and to date only, airplane trip of my life. We had a magical week, walking the city day and night, miles and miles and miles, and it seemed like every time we turned a corner, there was another iconic sight — a building or a street or a park that felt deeply familiar despite our never having been there before. New York City really is America’s city, it seems, so ubiquitous in our popular culture that even rubes from Kansas know it well.

We had the pizza, we had the cheesecake, we saw Joey Ramone at CBGB and King Missile at the Sidewalk Cafe in the Village and even met the delightful Dogbowl for a drink. We took in the marvelous views from the 86th floor observation deck of the Empire State Building, basked in the breathtaking glory of the Chrysler Building’s High Deco lobby and enjoyed a meal accompanied by a lovely samba-vibe lounge act in the historic intimacy of Marion’s Continental Restaurant & Lounge in the Bowery.

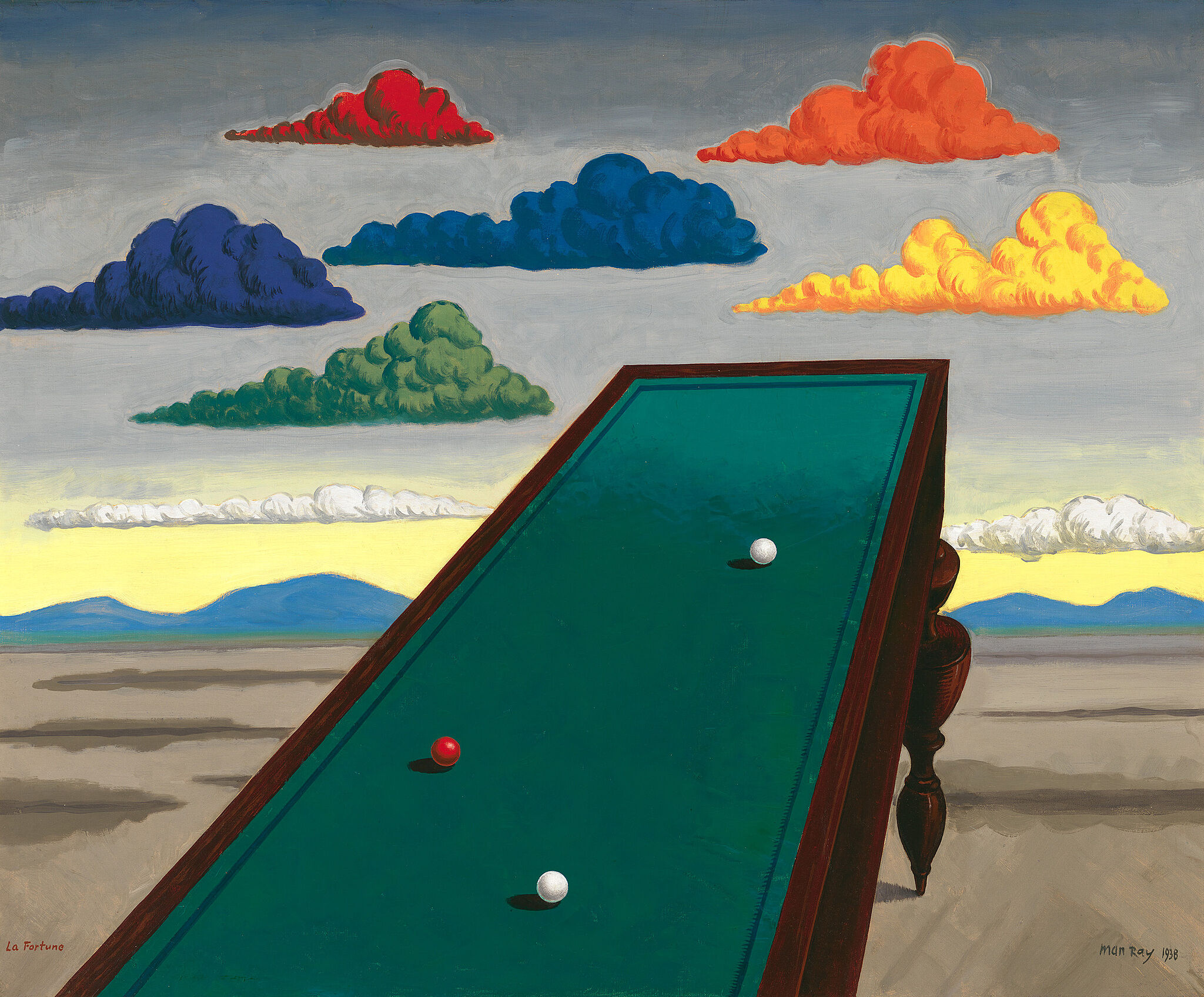

The Guggenheim was closed the day we went, but the Whitney was open and had several excellent shows going on, including a Barbara Kruger retrospective and an Edward Steichen exhibit which included examples of very early color photography, some of it presented on backlit glass plates. I gasped audibly when I rounded a corner and came face to face with a beloved Man Ray painting I had only seen reproduced in books.

We fed squirrels in Union Square, Tompkins Square and Central Parks, each with their own personality. The Yankees won the American League pennant that week and the whole town erupted in celebration as preparation began for the Yanks to take on the Mets in the Subway Series.

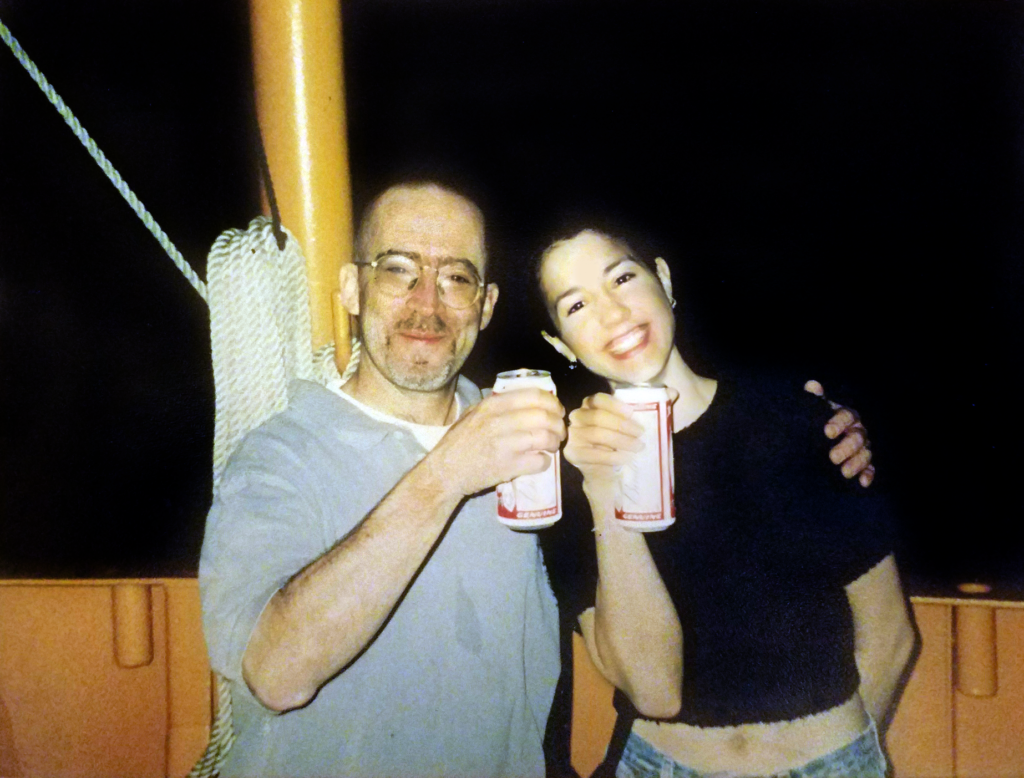

The indefatigable David Sheets, since passed, took us on an epic walking tour — first of the area around Brighton Beach and Coney Island and then, after a train ride, the whole of Lower Manhattan. Wall Street, the World Trade Center, the Battery. We got on the Staten Island Ferry and drank 16 oz. cans of beer on the trip out there and back, just to do it. It remains to date the only time I have been on anything like an ocean. I bought a Communist newsletter from a guy on a train and then drunkenly left it in a bar.

For our last night in town we packed up our microscopic hotel room on 86th Street West and took a series of trains and buses down the island and through the Lincoln Tunnel to Union City, New Jersey, where Lucy’s cousin Iggy and his family lived. We stayed our last night there and Iggy drove us all the way up to LaGuardia the next morning to catch our flight back home. We couldn’t have had a better time.

In the months that followed, Lucy and I settled into married life. With more than a little help from her kind parents we moved out of a duplex with a tragically leaky basement to our own house just west of Wichita’s VA Hospital. And, less auspiciously, I started taking prescription psychotropic medication, something I had never really done before.

Honestly now I can’t remember if I started taking them before the trip to New York or not, but I don’t think so. Despite my lifelong reputation for having an incredibly sharp memory, this period reports back to me now through a kind of fog that I have every reason to assume must be due to this program of medication. At any rate, it started when I was seeing my general practitioner about something comparatively trivial — I think I was suffering through a long period of allergy attacks. My doctor overheard me mumbling under my breath as I worked through one of my OCD loops* and when he asked about it, I told him.

(*What I call an OCD loop I don’t really have another name for but I do these things in my head having to do with numbers, syllables in words and phrases, religious chants/prayers, etc. It’s exhausting.)

Without batting an eye, my GP wrote me a prescription for Paxil, a popular drug among a class known as Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors, or SSRIs for short. These drugs treat obsessive-compulsive and panic disorders, depression and related mental ailments by blocking the brain’s reabsorption of serotonin, one of the key chemicals released by the brain in normal operation. I agreed to try it.

Within a few weeks I was fully wired on the stuff and not at all enjoying it. I became hypervigilant to the point of extreme paranoia. I barely slept and my brain felt like it was on fire. In the dead of one black, moonless night I heard the doorbell ring and shot straight up in bed, my heart beating like a racehorse’s. I crept to the bedroom window and looked down but saw no one on the porch. This only made me sure that the unseen caller was stalking the house from around back. I crept silently down the stairs to the kitchen and pulled a butcher knife from a drawer, then tiptoed from one window to the next, cautiously peering out into the empty darkness of our yard on Bleckley Street. Finally, after what must have been 30 minutes of prowling the lower level of the house, I quietly made my way back upstairs, sat on the edge of the bed facing the entry to the room, and clutched the knife until dawn broke through the windows.

By this time I had started seeing the psychiatrist my GP had recommended to monitor my new course of treatment. I didn’t like this guy, which is in my experience not a good relationship to have with your shrink. I told him about the negative side effects I was having with Paxil and he suggested I move over to another SSRI drug, Zoloft. I said OK.

It only took maybe a week before I noticed a difference between the two drugs. With Paxil I felt like I was on some sort of bathtub speed all the time, my skin crawling, unable to relax for a second. The Zoloft was exactly the same — except I suddenly also had enormous trouble getting an erection, and when I did manage, I was entirely incapable of reaching climax. This would not do, either.

I spoke with my psychiatrist about this at our next meeting and he knitted his brow in concern and said he was going to try a whole different tack with my treatment. He took me off SSRIs altogether and switched me to Wellbutrin, an NDRI (Norepinephrine and Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitor). It does roughly the same thing as an SSRI but moderates two other chemicals secreted by the brain rather than serotonin. The shrink was concerned about the extreme nervousness I had experienced on the first two drugs and the risk of seizure(!) posed by taking Wellbutrin, so he also prescribed me Depakote — a “mood stabilizer” drug used to treat epilepsy, bipolar disorder, migraine and some other pretty serious brain maladies.

Now this… was something different. The world slowed down around me, the volume on everything was turned down. I felt like electricity was running through my body all the time, but in a good way. It honestly reminded me of the handful of times I had smoked opium, just an all-over feeling of vibrating warmth. Sometimes when people spoke to me my attention would fade and they really would begin to sound like the unseen adult characters in a “Peanuts” special.

I don’t for the life of me now remember what I was doing for a living at the moment or if I even had a job. I was sleepwalking through every day, numb to outside stimuli. I could barely muster up concern at the drooling zombie who began appearing in my bathroom mirror, and when I brought it up to my shrink, he waved away my misgivings, assuring me that I was vastly improved. I said OK and kept taking the drugs.

And then there we were in September 2001, as usual setting up our campsite at the Walnut Valley Festival in Winfield. The official festivities didn’t start until Thursday, but the campgrounds started filling up a week ahead of time, and we enjoyed the extra few days of relaxation each year, so we always came and set up on Saturday or Sunday the weekend before. We spent the next couple days sitting around our campsite, rolling cigarettes and playing guitars, cooking over open fires and Coleman stoves. We drank beer and had laughs and exchanged warm greetings and big, sincere embraces at the sight of old friends.

On Tuesday morning I woke up in my tent, my mouth dry and my bladder full. I wondered what time it was — not that it really mattered while “on Winfield time.” I dug around in the little pouch sewn inside the wall of my tent to find my glasses and my wristwatch. It was a little after ten in the morning, which meant I had slept more than eight solid hours.

But that was no surprise given the cocktail of drugs I was on, which continued to keep me suspended like a sloth in molasses. I dozed heavily and frequently in those days, perhaps making up for the several months of sleep I had lost earlier in the year.

It was starting to get a little stuffy in the tent as the sun crept upward in the sky, and I really had to pee. I pulled on a t-shirt and a pair of cutoff jeans and my canvas slip-on sneakers and unzipped the tent and slowly unfolded my lumbering frame out through the opening into the fresh autumn air. The campsite we shared with several other folks was deserted, save for our old friend Steve Schroeder (RIP). He was sitting several yards to my left in a camp chair, smoking a cigarette and listening to the news on a cheap plastic radio that was also a flashlight, branded with the name of a local credit union. He looked up at me but before he could say anything, I pointed to the line of porta-johns across the dirt road and shuffled briskly that way.

As I emptied my bladder in the sparkling fresh “blue room,” which had just been sucked clean of the previous day’s waste and refilled with minty blue antiseptic fluid, I wondered to myself, “What was that look on Steve’s face?” It hadn’t really registered in that brief moment outside the tent, but now I was finally decoding it — was something wrong? God, I was so slow on the uptake.

I finished up and walked back across the road. It was very quiet out, as it was only Tuesday, and a lot of people didn’t actually show up until the official beginning of the festival on Thursday. But even our campmates were absent. “Where is everybody?” I wondered. I approached Steve, sitting there next to the white plastic patio table with an umbrella poking up through its center, clutching the radio in both hands in his lap, staring at it. He looked up as I approached.

“Hey, Michael, listen to this,” he said, turning up the volume and holding the radio up toward me. I reached for a nearby chair to sit, and just as I plopped my ass down, I heard:

THE PENTAGON IS STILL BURNING.

I looked up at Steve and now his expression was unmistakable. Something terrible had happened.

“What’s going on?” I asked as the newsman chattered away.

“They think it’s some sort of terrorist attack,” Steve replied. “Somebody has hijacked several planes and run them into buildings. They hit the World Trade Center too.”

Though I immediately grasped the terrible gravity of this situation on a rational level, the cocktail of Wellbutrin and Depakote in which my neurons were swimming precluded any deeper emotional response. I absolutely knew I should be totally freaking out — after all I have always been overly empathetic and emotionally anxious — and so on top of processing this sudden catastrophe, I was also processing my own reaction to it, or rather the lack thereof.

I bummed a cigarette off Steve and we listened in silence as various correspondents and news anchors related the latest updates, recapping the whole of the morning’s terrible events as the more complete picture unfolded. The Twin Towers, one by one. The Pentagon. Flight 93 going down in a Pennsylvania field. The atrocities piled up one atop the other.

We had no smartphones, not even cell phones. There was no googling the latest updates. Everybody else in the world sat glued to their television sets, watching the horrific footage over and over again, while we sat outdoors in folding chairs on a grassy knoll, bereft entirely of visuals to accompany the story. Our only connection to the outside world was through the radio, to which we listened in stunned silence for hours.

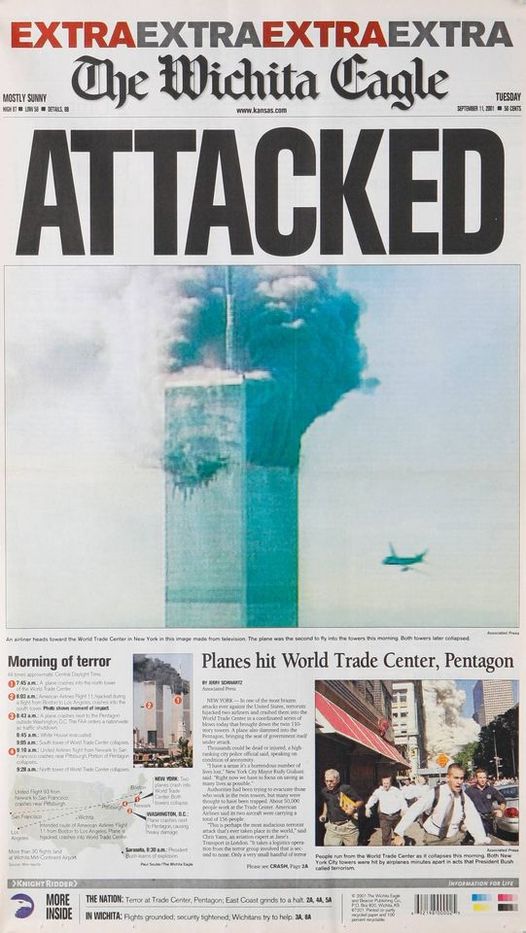

Later, in the afternoon, a station wagon slowly wound its way up and down the dirt roads in the campgrounds, selling the extra edition of the Wichita Eagle rushed out to cover that day’s shocking events. ATTACKED, the headline read in black letters four inches tall, above a massive photograph, captured from videotape, of Flight 175 just about to smash into the south tower, as the north tower burned. Everybody was buying copies for 50 cents, myself included. I sat down to read, but there was no new information, just the same wire service stories that we had heard repeated all day on the radio.

Somewhere across the Pecan Grove, a group of people, men and women, began playing music together, guitars and banjos and mandolins. They raised their voices in harmony, singing the old time gospel number “I’ll Fly Away.” The song, with its theme of spiritual release in flight, struck me as ironic, as the skies overhead were now eerily empty, all plane traffic nationwide having been grounded in the wake of the attacks. Nobody was flying anywhere, not even some of the acts scheduled to appear at the festival later in the week. The sounds of the singing, wafting on the gentle September breeze, was exquisitely beautiful, so sweet that it almost pierced the chemical veil shrouding my heart.

And then this same group of unseen musicians started to play “This Land Is Your Land,” and I really knew I should be feeling it — but I was not. Nothing had ever felt so wrong to me.

“I have got to get off these fucking drugs,” I told myself.

I did not see a solitary lick of television until the following Sunday, when Lucy and I returned home from camping at the festival. But even five days later, the footage was still being replayed nonstop. The planes striking the buildings, the tiny frail human forms falling to Earth one by one in their last seconds of life, the collapsing of the mighty structures, the clouds of dust and smoke and debris. The horror. The horror. I watched helplessly like everyone else had been doing all week, frozen inside and out.

The next day I called my psychiatrist’s office to tell him I was going off my meds, and to ask him for the best way to taper off of them. I got his answering machine. He called me back personally, not his receptionist, and advised me against it. I told him, “I can’t live like this.” He warned me that I must taper down my dosages slowly, especially with the Depakote, as sudden cessation could cause unstoppable, ongoing seizures.

“I’ll take my chances, Doc,” I told him. I hung up the phone and never spoke to him again.

Slowly I came off the drugs and started feeling more like my old self — depressed, anxious, prone to emotional outbursts, riddled with suicidal ideation, compelled to count syllables and chant prayers under my breath — but at least able to feel normal human emotions.

The fog lifted over a matter of weeks but I endured SSRI aftereffects — “brain zaps” the most unnerving among them — for the next seven years. They finally faded, too, thankfully. Later still, through my quasi-Buddhist practice, I managed to get (mostly) on top of my OCD, though it still flares up when I experience extreme stress or anxiety.

And every year when 9/11 comes around, like most everybody else I think of all the lives lost, and of the national unity squandered in the wake of the terrible events of that day. I think of the unsavory national policies made in response, and the war launched using it as a flimsy premise, and the greasy politicians who continue to reduce it to a campaign buzzword. And the only microscopic bit of good I can find in it is that it got me off those drugs. I guess that’s something, anyway. The most threadbare sliver of a silver lining — but for me, it’ll have to do.