A media magnate blanketing the nation with wall-to-wall political propaganda and misleading advertising. A snake oil salesman running for high public office, using an ersatz mixture of populism and religious fundamentalism. A notorious quack becoming rich by preying on the vanity of middle-aged, wealthy people eager to reclaim the lost vigor of youth. A powerful fraud buoyed by an unshakable fan base as he rails against the persecutors who expose his crimes. No, it’s not today’s headlines — these are just a few highlights from the extraordinary life of Dr. John Romulus Brinkley (1885-1942), one of Kansas’ most spectacular and bizarre historical figures.

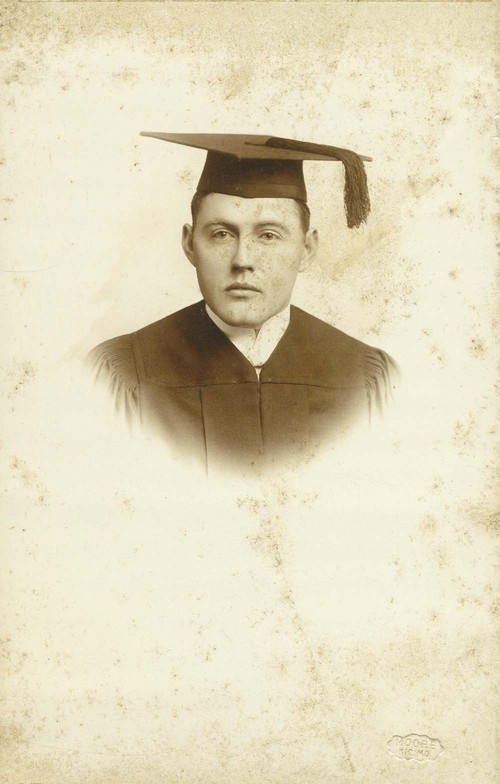

Young John’s beginnings were inauspicious in the extreme. He lived in meager circumstances with his father, a North Carolina mountain man who had served as a medic in the Confederate Army, the old man’s wife, who John called “Mother” — and her niece, Brinkley’s actual mother, known to him as “Aunt Sally.” John lost “Mother” at five and his father at ten, leaving only Aunt Sally to take care of him thereafter. He went to school when there was one available and took on paying work when and where he could find it.

By age 16 the young man was delivering mail in area communities and had learned to use a telegraph machine. This skill would serve him well, earning him positions in New York City with the Western Union company, then later a New Jersey-based railroad office. He was making a decent living, but remained unsatisfied with his station. Since childhood he had been impressed with his father’s extensive knowledge of the healing arts, and he burned with the desire to formally study medicine.

Aunt Sally took ill in 1906 and John, only 21 years old at the time, raced back to his old hometown to be at her side. She passed on Christmas Day, and in the weeks that followed, John took up with an old schoolmate of his, Sally Wike. They were married by the end of January, and in the days that followed, John R. Brinkley cooked up the first of many, many scams he would go on to perpetrate on a gullible public.

Sources vary on the exact details, but in 1907, John and Sally Brinkley are said to have posed as Quaker healers, traveling from one small town to another, putting on a show to peddle some sort of patent medicine John had concocted. Other stories are told of John working alongside a more established grifter, Dr. Burke of Knoxville, Tennessee, in pushing phony virility tonics. They appealed to the insecurities of people with more money than sense, and they raked it in. But John realized this shady sideshow business could only take one so far, and he figured that he could make a lot more — if only he had proper medical credentials.

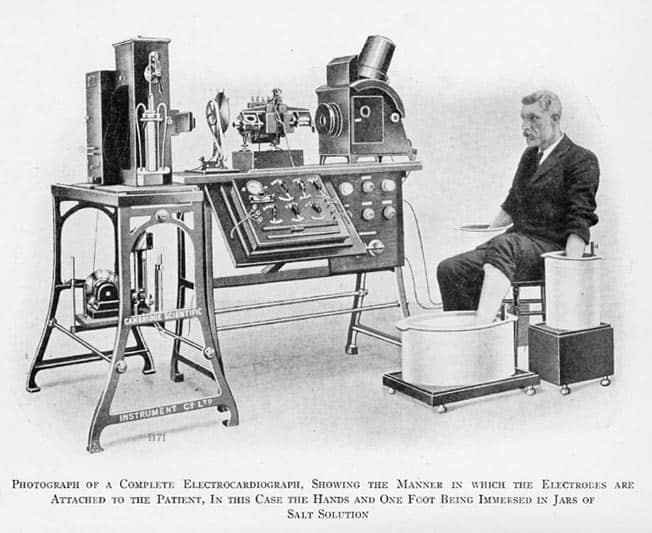

Sally was skeptical, but John was serious, and soon the young couple and new baby daughter Wanda were living in Chicago, where Brinkley attended classes at the shady Bennett Medical College — itself a for-profit grift operated by the school’s own dean. Bennett’s focus was on “eclectic medicine,” a field of alternative study and practices which in those days openly characterized itself as a legitimate challenger to “scientific” medicine. It was here that John Brinkley first became fascinated by reports of the effects of glandular extracts on human health, at the time an area of clinical study that regularly wielded breakthrough discoveries. His lifelong preoccupation with glands was born.

Brinkley would attend Bennett for three years, all the while working double shifts for Western Union and scrambling to keep his marriage together. At one point Sally left him, and in a desperate bid to get her to take him back, John abducted their daughter and fled to Canada. The ploy worked — but not for long. Sally went back to North Carolina, and Brinkley followed her, dropping out of school. By this point he had sired two additional daughters, and the couple had lost a son to miscarriage.

Brinkley felt he was so close to getting the medical degree he needed to start a legitimate practice, and he champed at the bit to get back to his studies. Unfortunately, as he still owed Bennett Medical College a substantial amount in back tuition, that school refused to release his transcripts, and he was unable to enroll anywhere else. Sally, fed up, finally left him for good, taking their three daughters with her.

With the perpetual naysayer Sally out of the way, John Brinkley was free to really spread his wings and fly. In 1913 he and a fellow named Crawford went into business together in Greenville, South Carolina, opening a clinic called “Greenville Electric Medic Doctors.” Advertising the latest in cutting-edge European treatments for men who had lost their “manly vigor,” Brinkley and Crawford (operating under pseudonyms) employed quack electrical devices and injected their patients with what was purported to be the latest miracle drug, Salvarsan, but was actually only colored water — for $25 a pop (roughly $750 in 2022 money).

The two charlatans did a swift business, but after a few months of racking up bills with local merchants and writing bad checks all over town, they both simply split one day, leaving the sheriff furious. He dragged them both back to Greenville for trial, but not before Brinkley met in Memphis the true love of his life, Minerva Jones, known to her friends as Minnie. The second the two of them first laid eyes on one another, it was all over. Despite the fact that John was still legally married to Sally, he and Minnie tied the knot only four days after their introduction — and would remain together until his death.

After settling his legal woes in Greenville and divorcing Sally through the mails, Doc Brinkley and his new bride settled in Arkansas, where state medical licensure standards were lax, and he could legally practice medicine as an undergraduate. He struggled financially at first, but upon taking over a retiring doctor’s office, his income increased substantially. Finally able to pay off his back tuition and get his transcripts from Bennett, Brinkley was more than ready to finish his degree. He enrolled in another rather notorious institution, a diploma mill called the Kansas City Eclectic Medical University, and in 1915, he was issued a certificate that allowed him to practice medicine in eight states, including Arkansas. Once he passed the Arkansas state medical exam, he was then able — due to a reciprocity agreement — to practice medicine in Kansas, as well.

The timing could not have been more perfect. After a brief sidetrack into the Army (he wriggled out), Brinkley, tired of bouncing around from place to place, longed to settle somewhere and put down roots. He just knew something big was right over the horizon; he could feel it. And then one day, as he sat reading the newspaper, the opportunity of a lifetime presented itself in the form of a small printed want ad: The good people of a one-horse town called Milford, Kansas needed a doctor.

In October 1917, they got one.

Doc Brinkley was an instant smash in Milford. He and Sally had arrived just in time for the terrible 1918 flu pandemic, and by all accounts, he immediately endeared himself to the citizenry with the care and attention he doled out to countless ailing patients. He opened a large clinic and staffed it well, drawing in business — and money — from surrounding communities and the many isolated farm folk in the area. The town fathers were very keen on him, right away.

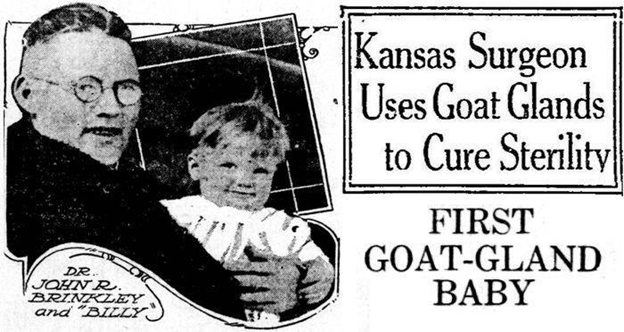

A year later, Brinkley’s legitimate medical practice was making him a very good living — but not enough for his taste. Resuming his “experimental” activities in the field of male vigor, he did his first famed “goat gland” surgery, implanting into the scrotum of a healthy middle-aged man slices of goat testicle. The patient, the stories go, had been trying in vain for years to conceive a child with his wife, and was willing to try anything that might help. The good doctor was more than happy to oblige, for a price.

It could have ended there, a half-forgotten local legend about a crazy doctor who did some wacky experiments that went nowhere. Dr. John R. Brinkley might have been remembered, if at all, as a laughingstock. The larger world might have been completely ignorant of his having ever existed.

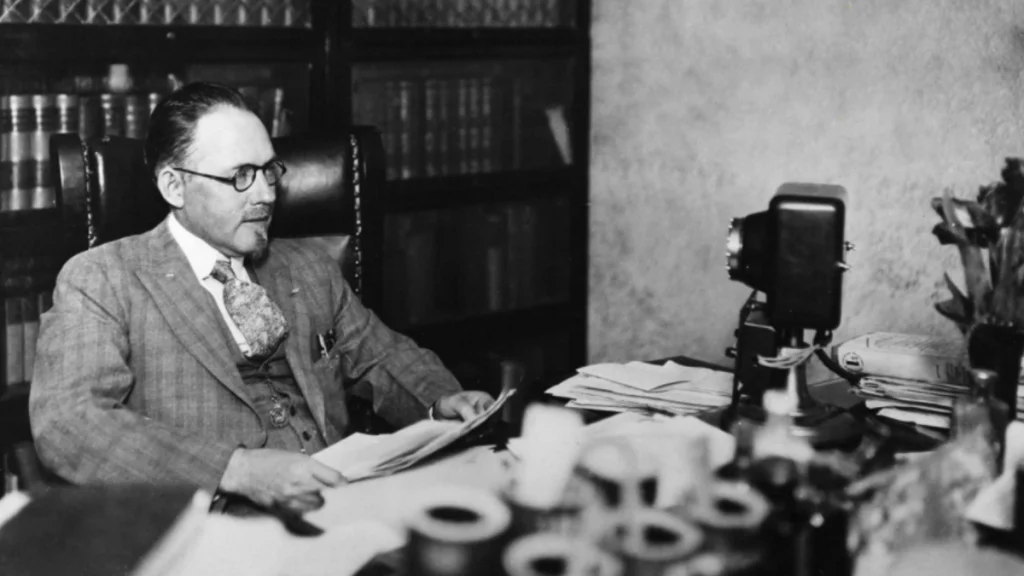

But then something unexpected happened. Shortly after that very first goat gland operation, the patient’s wife became pregnant. One imagines nobody was more surprised by this than Brinkley himself, but naturally, he was quick to capitalize upon this apparent success. The story attracted the attention of numerous big-city newspapers, and soon pictures of the bespectacled doctor holding the “miracle baby” appeared in broadsheets from coast to coast. Following on the heels of this exposure, Brinkley made one of history’s first direct mail advertising blitzes, marketing his services across cities far and wide. By this time, he was claiming his experimental treatments treated more than two dozen ailments of the body and mind — and in response, the world beat a path to his door.

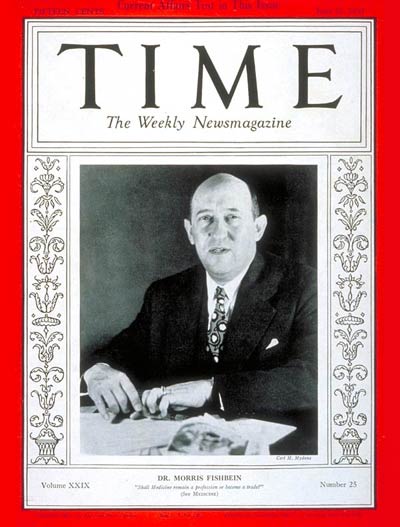

But all this attention was bound to draw unwanted scrutiny from the medical authorities. Brinkley’s hospital in Milford was infiltrated by an undercover reporter working for the American Medical Association, who was horrified to find, among other major red flags, a woman staggering around in agonizing pain, recovering from a surgery in which goat ovaries had been implanted in her body as a treatment for cancer. The editor of the Journal of the AMA at this time was Dr. Morris Fishbein, a virulent anti-quackery crusader. He was so outraged by the report that came back from Milford that he immediately made John R. Brinkley the number one target on his list of public enemies.

Meanwhile, Brinkley just kept on scoring major publicity coups, including a surgical exhibition in Chicago, in which he implanted goat gonads into 34 patients in a row, including numerous city officials. The Los Angeles Times challenged him to a demonstration, and when they were satisfied with the results, Brinkley basked in the free press. It is said that a few early movie stars visited his hospital in Kansas, and Brinkley dreamed of opening a facility in Hollywood — but the AMA made sure California would not grant him a permanent license based on his shoddy credentials. It was a blow to his vision, surely, but in the end his visit to the Golden State ended up giving him a much greater gift.

While in Los Angeles, Times honcho Harry Chandler gave Brinkley a tour of his new radio station, KHJ. Radio was, at the time, quite a newfangled technology, with receivers found in only one percent of American homes. KHJ was one of the first three dozen licensed commercial stations in the entire country, and as an investment represented an enormous roll of the dice — but Chandler’s optimism about radio’s prospect as a medium was infectious, and Brinkley instantly saw its potential for extending the reach of his advertising. He looked up at that tall broadcast tower and saw his future.

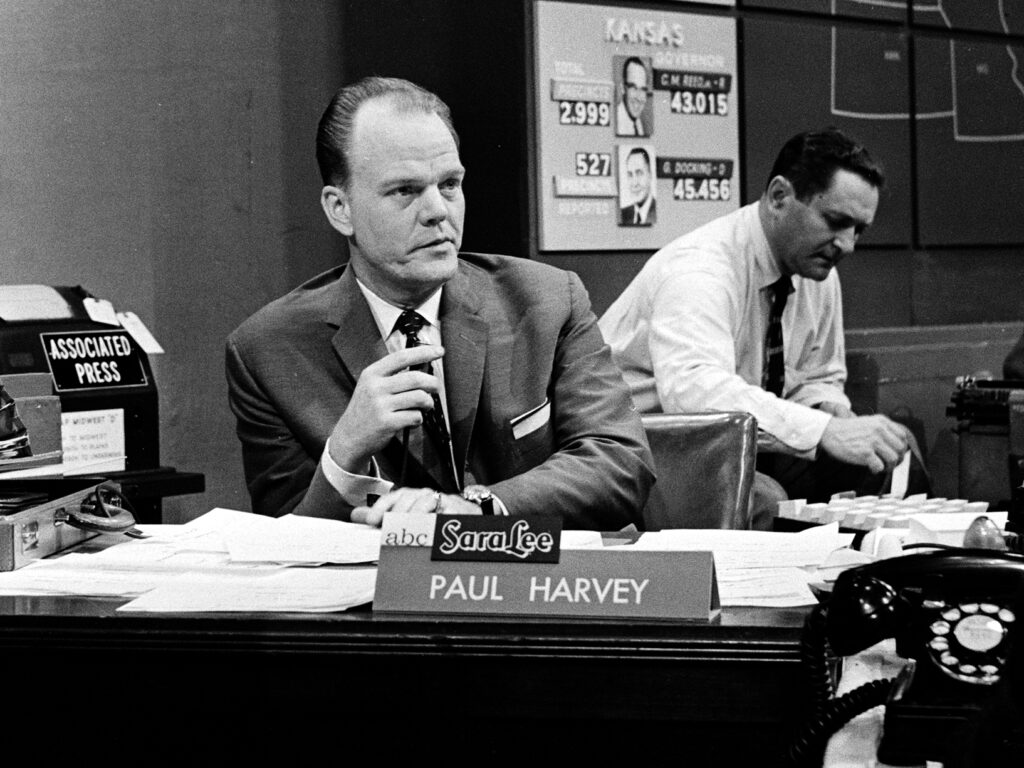

Within a year, Doc Brinkley had established KFKB radio, a 1000-watt (later 5000-watt) station operating out of Milford — which, incidentally, had become something of a boomtown thanks to the doctor’s fame. The radio station not only further raised the growing community’s profile, but paid off personally for Brinkley right from the start. When California tried to have him arrested for including what they considered worthless credentials in a state license application, Kansas governor Jonathan Davis refused to extradite his favorite cash cow, and Brinkley went on-air to crow about his triumph over the oppressive forces of government. He filled the airwaves day and night with his own lengthy testimonials to his prowess as a surgical savior of the masses, interspersed with blocks of country music, comedy bits, news and sports updates, lessons in foreign languages, horoscopes and whatever else he could come up with to keep people engaged and tuned in.

And here he once again became a pioneer, launching his Q&A radio show “Medical Question Box,” in which Brinkley read letters from listeners detailing their health concerns. (Imagine Car Talk, but for people.) Whatever the ailment, the recommended course of action typically involved the patient hurrying down to the nearest “Brinkley Pharmaceutical Association” affiliated druggist to buy one of the good doctor’s proprietary potions. Hundreds of pharmacies participated in this program, stocking and selling Brinkley’s mostly bogus products, and his ability to hawk them directly to thousands of listeners over the airwaves was soon netting the doctor a tidy profit of $14,000 a week (nearly a quarter-million dollars today).

Bear in mind that the concept of commercial media bombarding the citizenry over the air with advertising was at the time not only new but frankly considered gauche in the extreme. A lot of people in the nascent radio biz were uncomfortable with Brinkley’s baldfaced on-air hucksterism, and alarmed at the fact that so many workaday folk seemed practically addicted to his never-ending stream of quasi-infotainment. The FRC —Federal Radio Commission, forerunner to the FCC — refused to renew Brinkley’s license in 1930, endangering his entire empire.

If that wasn’t enough, a scathing exposé by the Kansas City Star prompted the state medical board to review Brinkley’s qualifications. They found he had signed no fewer than 42 death certificates in Milford, many of them for patients who had walked into his hospital in perfectly ordinary health. The Great State of Kansas jerked his license.

Now Brinkley really had to pull a rabbit out of his hat. Though he was barred from practicing medicine in his state of residence, his existing radio broadcast license was still good for another few months. How best to exploit this precious platform before it slipped away?

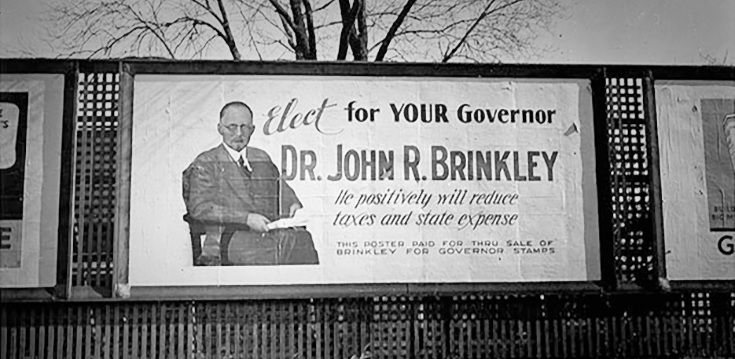

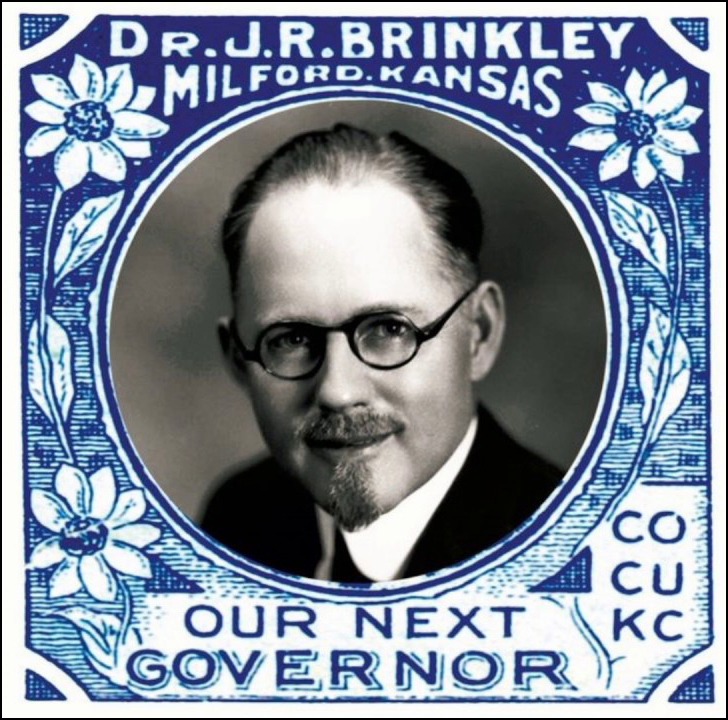

In September of 1930, just three days after his medical license was rescinded, John R. Brinkley went on the radio and announced his candidacy for the Kansas gubernatorial race, to be decided on November 4 of that year. If he was elected, he figured, he would be able to appoint new (sympathetic) members to the state medical board and get his license back, easy peasy. It was a plan so crazy, it just might work! Due to his late entry into the contest, and lack of party affiliation, he had to run as a write-in candidate, but he saw that as no real obstacle — after all, wasn’t he the most famous man in the state?

Yes, he was. And the officials in Topeka, the state capital, knew it too — and they were not happy about it. As the election drew nearer, nobody could match Brinkley’s ability to reach voters, as neither Democrat Harry Woodring nor Republican Frank Haucke had 24/7 access to a radio station with the widest listenership in the United States. Nor were either of them folk heroes like Doc Brinkley. Everybody knew this dark horse was the favorite to win, and it scared the shit out of them.

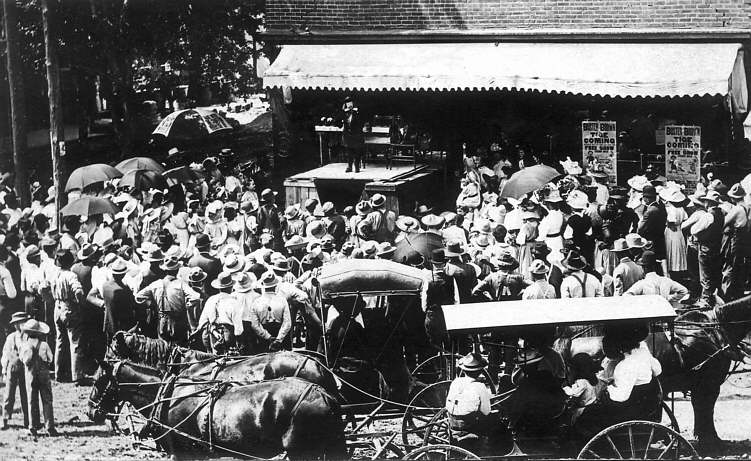

The state attorney general, William Smith, was under pressure to do something to level the playing field. As Election Day drew near, he came up with a simple but effective plan: cheat. Smith issued a surprise edict specifying that write-in ballots for the doctor must be written exactly like this: J.R. Brinkley. Not JR Brinkley, not John R. Brinkley, not Doc Brinkley, not John Brinkley, not Brinkley. The good doctor turned to the radio to make sure everybody knew it had to be, “J, period, R, period, Brinkley!” With little time to campaign, he put together what may have been the first loudspeaker truck in the country to make speeches in the street, and barnstormed all over Kansas in a flashy private plane, promising a state lake in every county and state-backed pensions for the old folks. The people ate it up.

After the election, it took twelve days to count the votes, and indeed, write-in ballots for Brinkley easily outnumbered those for either of the other two major candidates. In fact, he beat the second-place contestant, Woodring, by nearly 20,000 votes. But then came the culling of the ballots with improper spellings. When the dust settled, a total of roughly 50,000 pro-Brinkley votes were thrown out, and he fell from first place to third.

Doc Brinkley could have challenged Attorney General Smith’s last-minute rule about the spelling of his name, as legal precedent existed in Kansas protecting a voter’s obvious intent in a write-in ballot, regardless of spelling or punctuation. But he was already hatching a bigger plan yet, and it was going to be truly spectacular.

Here a little radio-biz backstory is in order. When the FRC first started dividing up radio frequencies and handing out broadcast licenses, they allotted to the US the prime real estate of the airwaves, threw Canada a bone or two, and completely ignored Mexico. The Mexican government, as one might imagine, was rightfully pissed about this. So when Dr. John R. Brinkley showed up with plans to build an enormous radio transmitter practically inches from the US border on Mexican soil, Mexico welcomed him with open arms, largely out of spite. No amount of federal pressure sufficed to stop the project, and in October 1931, XERA went on the air.

On opening day, the station broadcast at 50,000 watts — ten times the power of the old KFKB. But the Mexican government allowed Brinkley to step up the power, first to 150,000 watts, and then to one million. At that point the signal was so strong that it is said to have been picked up by barbed-wire fences and the fillings in people’s teeth. Birds flying near the massive transmitter towers would die in mid-air and fall to earth. On most days, Brinkley’s voice could now be heard across the entire United States.

It really seemed like Brinkley was having his cake and eating it, too. He now had literally the most powerful radio station in the world, and it was untouchable by any authorities that might care to do anything about it. He relocated to Del Rio, Texas to be near XERA, and was issued a license to practice medicine in that state. He built more hospitals and resumed doing goat gland surgeries and other “experimental” procedures with renewed vigor. He made millions in 1930s money. In Del Rio he built an elaborate mansion within sight of his radio towers, with 16 acres of gardens and a greenhouse and a musical fountain with colored lights. He bought a dozen Cadillacs, a new Lockheed Electra airplane, a yacht for deep-sea fishing, weird animals from foreign lands, every manner of flamboyance, all emblazoned with the name BRINKLEY in capital letters.

XERA featured the usual Brinkley grift programming, of course — a never-ending parade of new salves and elixirs and pomades and tablets, dubious in both effect and quality — but also proved influential on the mass culture by prominently featuring many country music acts, giving acts like Jimmie Rodgers, Red Foley and the Carter Family their first major nationwide platform. Additionally, Brinkley had taken to selling blocks of advertising airtime to other scam artists for the outrageous fee of $1700 an hour. Listeners might hear long-form infomercials selling all manner of nonsense, from “genuine simulated diamonds” to autographed pictures of Jesus Christ. There seemed to be no end to the money pouring in.

Brinkley, tired of driving back and forth across the border from his house to the radio station to make his loquacious radio appearances, figured out that he could go on the air live from his mansion over the telephone, and took to doing so regularly. The US federal government, still trying to shut down his operation, struck back in 1932 with the passage of the Brinkley Act, essentially outlawing the practice of broadcasting from a foreign nation a signal emanating in the States. Brinkley immediately foiled the feds by recording his spiels instead on transcription discs, then having them delivered by messenger boy to the radio studio, just a few miles away. (Brinkley is a pioneer again here, as programs recorded on disc and sent to radio stations became a widespread industry standard thereafter.)

Even though he no longer lived in Kansas, he ran another campaign for governor in 1932, netting an impressive 31% of the vote. It was not enough to defeat Alf Landon. Just as well, as this time around, Brinkley was really only running for the free advertising. His empire may have been born in Kansas, but it seemed clear that its future lay ahead in Texas. After a third half-hearted stab at the governor’s office in 1934, he closed down the Milford hospital and never looked back.

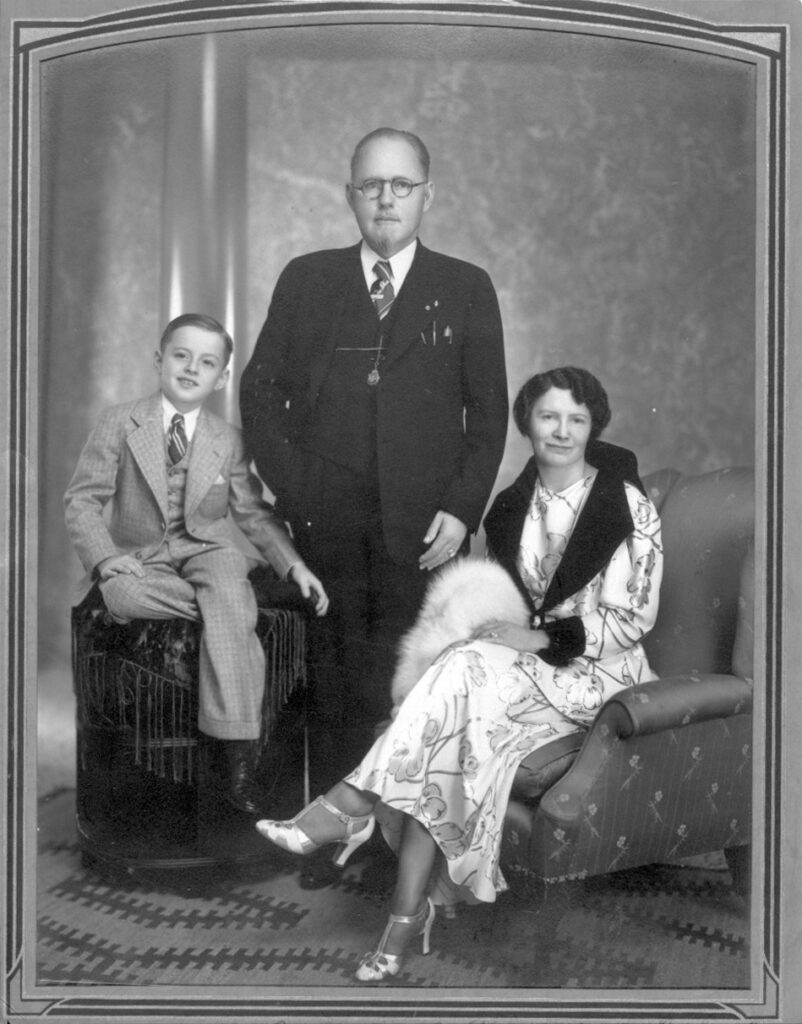

The mid-1930s were the best years for John and Minnie and their only child, “Johnny Boy.” They lived like kings, they moved in a society that adored them and they did whatever they pleased. And this was during the Great Depression, too, a time when a majority of Americans were suffering dire privation. The Brinkleys were truly blessed.

It couldn’t last.

The Mexican government finally started bowing to pressure from the US, chasing Brinkley off the air for short stretches of time, though he managed to keep coming back one way or another, including buying time on other border blaster stations. It looked like Brinkley’s rule over the wild west days of radio were coming to a close.

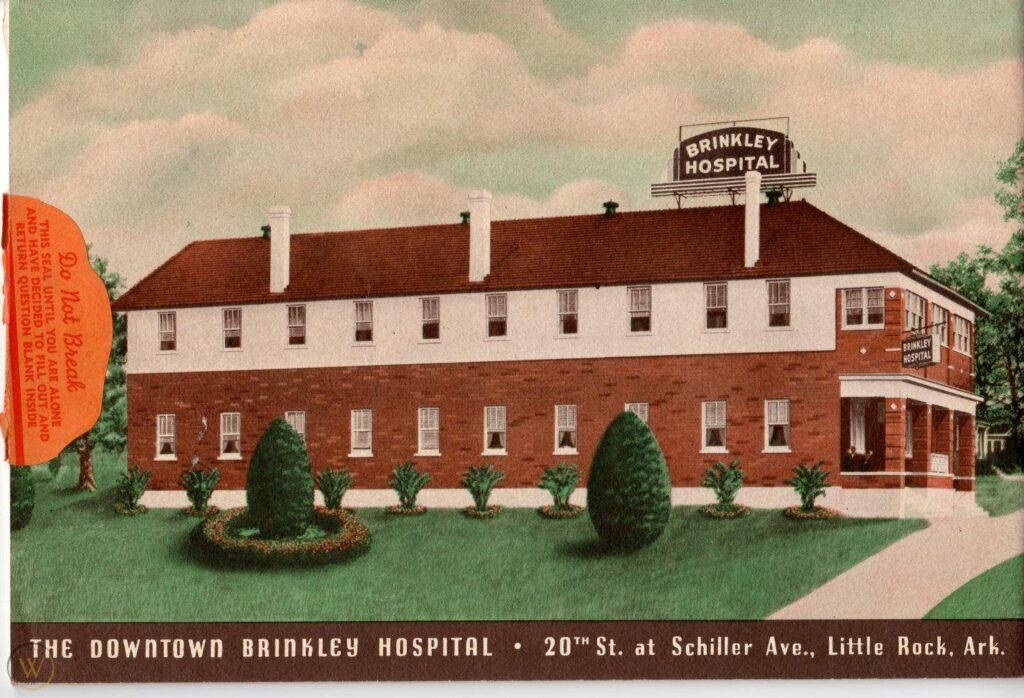

Adding insult to injury, by 1938, other charlatan doctors were horning in on Brinkley’s bit, including one with the balls to open a clinic right there in Del Rio, offering similar services at cut-rate prices. Brinkley pressured the city to give his competitor the boot, and when they refused, he moved his whole operation to Little Rock, Arkansas.

That’s when everything came crashing down. Brinkley’s old nemesis Morris Fishbein published a bombshell article excoriating the good doctor for his manifold rackets. Brinkley, letting his ego get the better of him, made the dreadful mistake of suing for libel.

In the ensuing court case, Brinkley’s legal team was stunned when the judge disallowed anecdotal testimony from the doctor’s past patients. No, only expert witnesses would be allowed to provide their opinions on Brinkley’s medical practices. Over the next three days, Dr. John R. Brinkley’s entire life’s work was meticulously and systematically revealed to have been a complete fraud by one expert after another.

Yes, he had performed some 16,000 goat gland surgeries, and countless various other procedures — but in court it came out that his habit of working while intoxicated had contributed to the untimely deaths of at least hundreds of people. A clinical scientist testified that the goat gland surgeries could not have possibly worked, anyway. And most damning of all, another expert divulged to the stunned courtroom — still filled with members of the doctor’s fan club — that his highly-touted Formula 1020, the latest of his many “wonder drugs,” was nothing more than colored water. And people had been paying $100 ($2100 today) for a package of six vials of it!

In the end, the judge had to agree with Fishbein. It was clear that Brinkley was the very definition of a quack, and that the only lies printed about him were those in his own flagrantly fabulated authorized biography — not in the JAMA.

Brinkley’s foolish libel case had opened a king-size can of worms, and he quickly found himself besieged on all sides by millions of dollars in lawsuits from angry consumers. XERA was seized by the Mexican government, on the grounds that Brinkley’s sympathies were a little too pro-Nazi for their taste. In 1941, Brinkley declared bankruptcy, citing debts of more than one million dollars. In September of that year he found himself indicted on 15 counts of mail fraud, and the IRS initiated its own tax fraud investigation, too.

Through all this, the good doctor’s health was going south fast. He suffered a series of heart attacks, and a blood clot forced the amputation of one of his legs. At long last, on May 26, 1942, his heart gave out altogether in San Antonio, and that was the end of Dr. John R. Brinkley.

Looking back on his legacy now it is easy to dismiss him as a mere carnival sideshow in the robustly weird history of America, but one must give credit where it is due. This incorrigible mountebank’s fingerprints can be readily seen all over America today — in our politicians and TV doctors who appeal to the downtrodden as they pick their pockets clean, in our media that broadcasts propaganda and advertising disguised as news, in our healthcare system where human life takes a backseat to profit, and even in our very physical environment, where one is never, ever exempt from being directly advertised to.

Dr. John R. Brinkley was a true founding father of the modern age, for better or for worse.

(Mostly worse.)