Over the years I have owned somewhere between 40 and 50 vehicles, the vast majority of them built in the 1960s-70s. Most of these were acquired quite cheaply, and in various states of disrepair — a fact that has, over time, required me to learn how to fix them on my own. Given that I have been doing this sort of thing for something like 37 years now, one might think that I would be pretty good at it these days, but to be honest I have always been more of a B- shade tree mechanic than a true Mr. Goodwrench.

A little over a decade ago I became a father for the first time, an event which roughly corresponded with my purchase of a brand-new Ford Fusion Hybrid sedan. Now my fifth-grader son Nash wants to be an engineer, and is quite keen to tinker on cars — but with the Ford being so extremely low-maintenance, we’ve had little opportunity to wrench on it. To date it has required little more than the occasional oil change, and our one big exciting day under its hood entailed changing the spark plugs for the first time, at nearly 100,000 miles.

So when a friend hit me up last spring, offering to sell Nash a 1974 Datsun 260Z for only $500, I was unable to refuse. We cleaned out our tiny, rickety garage, had the ancient Japanese sports car towed over, and set to work on Project Z ICT. In the months since, Nash and his little brother Moses have both found themselves enrolled in a crash course in Automotive Basics 101 — and the old man here has found his love for old iron amply rekindled.

I tell the boys they are lucky to live in a time when we can be in the garage with the car and pull out an iPhone to find step-by-step instructions on how to do a specific procedure, oftentimes even accompanied by a useful video. Not to mention the many vehicle-specific forums online, filled with helpful people who know lots about whatever type of car or bike you might be working on.

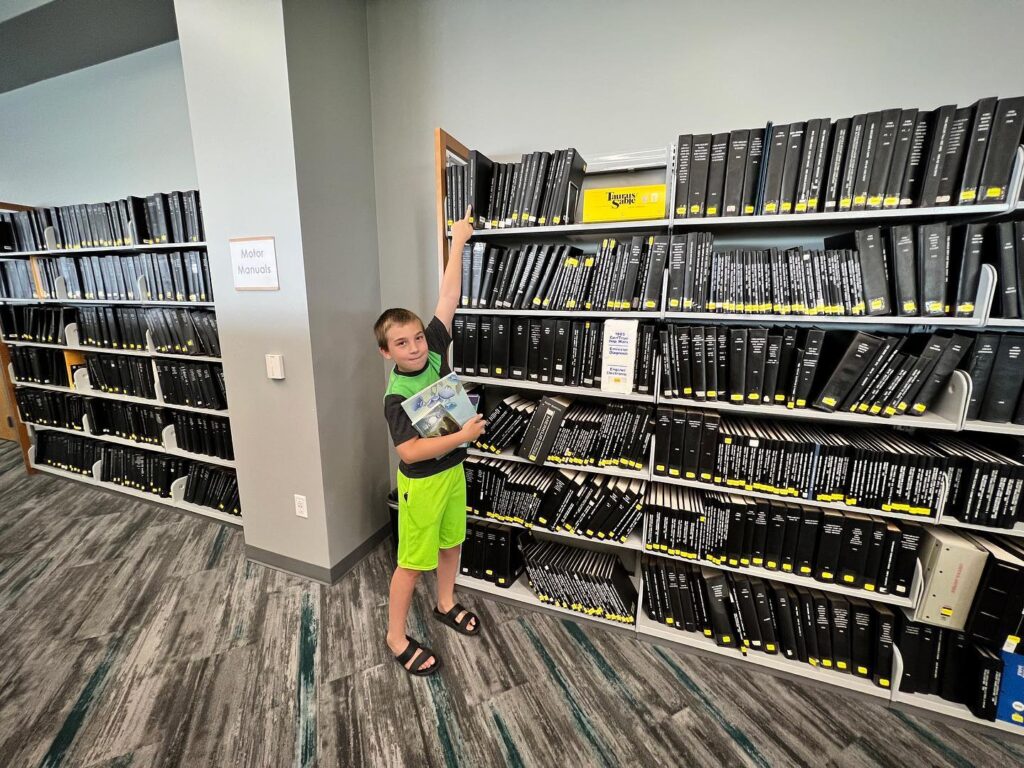

On a recent visit to the downtown Wichita Library, we found a whole wall full of hardbound automotive repair manuals, including no fewer than five that covered our Z car. My mind immediately went back to my first vintage ride, which I bought in 1986, at age 17. It was a ’63 Rambler, which at the time was scarcely two decades old, but in those days, when it came to finding information — and parts — it might as well have been built in the Cretaceous Period. Back then my hometown library had one Motor Manual that covered the 1963 American Motors cars, and as it was from the reference department, I was of course forbidden from either photocopying or checking it out. I took to bringing a notebook and pencil to the library with me so I could copy down precious information regarding spark plug gap, ignition timing, etc. This was truly automotive arcana, secret knowledge one had to search and fight for.

Likewise, the internet has made the present day a golden era for sourcing car parts. We recently purchased online a new radiator, water pump, fan clutch and several other vital parts, all quite inexpensive, for the 260Z — a car built halfway around the globe nearly a half-century ago. The one part we couldn’t find in stock anywhere was the harmonic balancer — but a friendly member of a Z car forum sold us a used one, which we then had rebuilt by a California shop that specializes in nothing but. It’s never been easier to work on a vintage machine.

Back in the ’80s, on the other hand, finding parts for my Rambler was some positively Indiana Jones shit. My small hometown mechanic once had to actually fabricate a component to make my clutch functional again, as there was no ready source for NOS or even used parts.

Well — almost none. As it turned out, there was in fact one place a person might find hard-to-get bits and bobs for their cars, trucks, vans and motorcycles — the legendary J.C. Whitney catalog.

It was my buddy Jay who first put me onto this publication, about a year before I came across the Rambler, right around the time my grandmother bought me my first-ever car, a 1980 Chevy Citation — just about as big a lemon as Detroit ever squeezed out its bunghole. I ordered a copy of the catalog using a form Jay had pulled out from one of his own, and before long, a new issue graced my mailbox every few months.

The J.C. Whitney catalog was a wild, glorious, bizarre thing — a full-color glossy cover wrapped around 250+ pages of the thinnest imaginable newsprint, each crowded to the margins with little boxes, and inside each box a line drawing of an item, accompanied by a BOLD ALL-CAPS HEADLINE and a description in type so small as to nearly require a magnifying glass to read. Despite the fact that I was living in the neon-colored future that was the 1980s, the J.C. Whitney catalog looked like it could have come straight out of my dad’s youth in the ’50s, or even my grandpa’s in the ’30s.

Of course the catalog was packed with the requisite mechanical necessities: fuel pumps, carburetors, mufflers, hubcaps, clutches, engine rebuild kits, intake and exhaust manifolds, and so on. But where it really shone the brightest was in its bottomless selection of accessories, ranging from the mundane (seat covers, window louvers, bug guards, curb feelers) to the absurd.

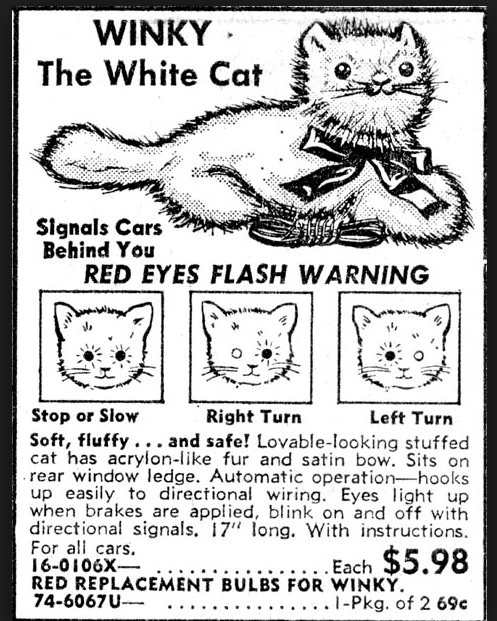

There was the light-up jester hood ornament, for instance. An assortment of replacement horns, including musical models, one that lowed like cattle, one that made sounds like a wild turkey, yet another that approximated the “wolf whistle.” Fake woodgrain vinyl shelf paper intended to give your car the “woody” station wagon look. “Winky the Cat,” a stuffed kitty designed to sit on the back deck of the car, inside the rear window, with eyes that lighted up to indicate when the driver applied brakes or activated a turn signal. An in-the-car coffeemaker. Replacement hoods to make your Volkswagen Beetle look like a Rolls-Royce or a 1940 Ford. Chrome-plated versions of just about every imaginable engine component. Stick-on “Eagle Styling Kits,” to give any car or truck that classic Smokey and the Bandit Trans Am vibe — available in multiple sizes! Weird shit.

The J.C. Whitney catalog was an endlessly fascinating, mysterious object, and its production clearly a staggering feat. Where did this thing come from?

The answer is truly one of the great American success stories of the 20th Century.

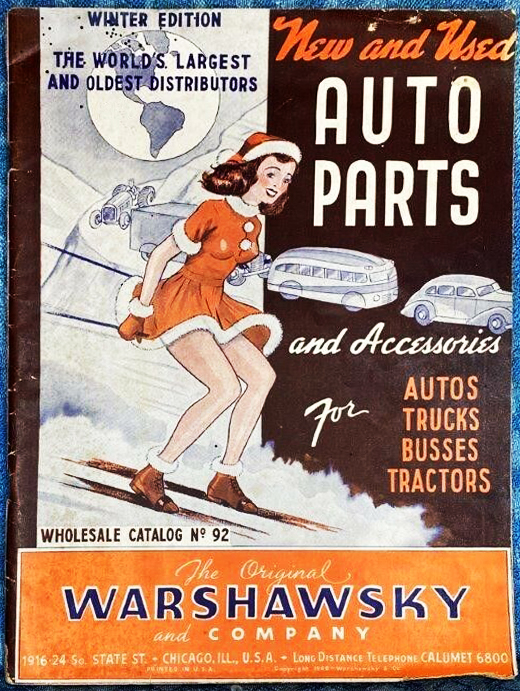

It starts all the way back in 1915 when a Lithuanian immigrant named Israel Warshawsky, who ran a metal scrapyard at the corner of State and Archer in South Chicago, watched with interest as sales of automobiles, led by the revolutionary Ford Model T, skyrocketed. Where go machines, Warshawsky reckoned, quite correctly, the need for spare parts must follow. He was among the first entrepreneurs in the United States to start buying up disabled and wrecked cars specifically for the purpose of stripping them and reselling their components. Before long he was doing a steady business, catering to home mechanics and small repair shops in the greater Chicago area, and opened a showroom dedicated to his parts trade.

Between 1900 and the 1929 crash of the stock market, literally scores of American automakers came and went, and as they failed, Israel Warshawsky was there to buy out their unused stock of parts at a tiny fraction of their original cost. His warehouses swelled, and so did his customer base — and his profits. During the Great Depression, when countless enterprises across the country went out of business overnight, his stock went up and up and up, as more and more people were forced to keep their old cars running rather than replace them with costly newer models.

1933 saw two important milestones in the history of the Warshawksy operation: the publication of its first parts & accessories catalog, copies of which were distributed to gas stations and auto repair shops all over the metro area; and the graduation from the University of Chicago of Israel’s rather brilliant son, Roy. A year later Roy would join the company officially, and things only looked up from there.

The younger Warshawsky was convinced that his father wasn’t thinking big enough. If Chicagoland alone continued to be this lucrative, imagine expanding the operation to a mail-order leviathan that would ship anywhere. It took some time, but eventually the old man came around and allowed Roy to place an ad in Popular Mechanics, promising a “giant” auto parts catalog to readers who sent 25¢ to their Archer Avenue address. Roy himself spent God-only-knows how many hours meticulously laying out the first edition, and was no doubt relieved when his predictions came true: The Warshawskys were positively inundated with catalog requests.

To nip in the bud any potential prejudice the decidedly Eastern-European name “Warshawsky” might engender in customers outside the Chicago area, Roy christened the mail order business with the more white-bread moniker “J.C. Whitney” — the “J.C.” taken from Penney’s, whose catalog he admired, and “Whitney” from his own childhood nickname — and they were off to the races.

The company grew and grew throughout the Depression and showed little sign of slowing down, even during World War II, when American automakers retooled their operations for the war effort. The Warshawskys took over the entire block, building ever more warehouse space and filling it with product. There seemed to be no end to their capacity to expand.

Israel died in 1943, leaving Roy in charge of the company, and for the next 50 years, the younger man absolutely revolutionized the aftermarket auto parts business. He showed up consistently at every trade show, personally spoke with manufacturers of parts and accessories all over the country and abroad, and even commissioned the production of literally thousands of specific items to be sold exclusively out of his warehouse, through his ever-growing catalog. Indy 500 legend Andy Granatelli’s Chicago-based family business, which built custom high-performance heads and other go-fast parts for Ford V8s in the 1940s, succeeded in large part due to the presence of their wares in the J.C. Whitney catalog.

By the late 1960s, Roy Warshawsky grew ever more concerned over various pieces of proposed legislation that threatened to take auto repair out of the hands of the Average Joe, and he decided if anybody was going to do something about it, it might as well be him. The first meeting of the newly-formed Automotive Parts and Accessories Association — today a formidable lobbying organization with thousands of members — took place in 1967, and Roy was unanimously chosen to represent the group as its president.

But the glory days were passing. The 1970s were a rough time for the US auto industry across the board, with the gas crisis, constantly-changing emissions and crash standards, a tidal wave of cheap and superior Asian cars, and increasingly complicated engine management systems, which made newer autos more difficult to work on for amateur grease monkeys. The Warshawsky outfit found itself faced with mounting debt and restructured under a federal bankruptcy plan in 1979. The show went on, they got over the hump, and continued selling up to a quarter-billion dollars annually in car parts.

Roy Warshawsky retired from the game in 1991, leaving the company to others in the family; he passed in 1997 at age 81. Five years later, his heirs sold the whole business lock, stock and barrel to a private equity company. Facing an aging customer base on one side and the internet drop-ship revolution on the other, J.C. Whitney’s new owners were stymied about how to go forward. They merged the brand with several other smaller acquisitions, most notably CarParts.com, but watched helplessly as their sales were poached by eBay and Amazon. The remains of the company left Chicago.

In 2015 I made my only trip to date to that Windy City, and while I was there I made a point of dropping by the location of the old block-long Warshawsky complex. I was saddened, but not terribly surprised, to find the whole area gentrified beyond recognition.

The last J.C. Whitney print catalog was produced in the year 2020, and its website redirected to CarParts.com, which today maintains one section — a selection of parts for Jeeps and other off-road vehicles — branded with the J.C. Whitney name. As of this writing, the last post on the accompanying @teamjcwhitney Instagram page was made over a year ago, in September 2021.

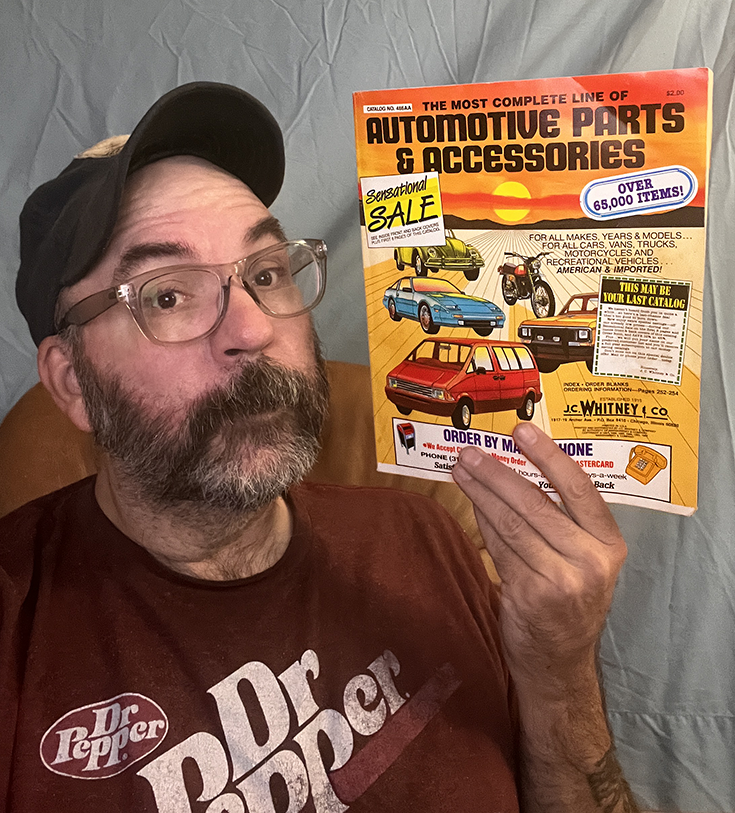

In preparation to write this story, I put out a call to my gearhead friends to see if any of them had an actual copy of a J.C. Whitney catalog from any era. Given that there must have been millions and millions printed, it seemed reasonable to expect that somebody would have one lying about. Nope. I finally resorted to poking around online and bought a 1987 copy — an edition I actually had first received as a teen — from a seller on eBay. Opening it and going through its translucent black-and-white pages from the remove of 35 years is an exercise in intense, instant nostalgia, and watching the boys’ genuine amazement with the sheer scope of its contents is very rewarding.

Now if only we could still get some of the more obscure 260Z parts found in there…